At the intersection of power, capitalism, identity politics, and feminism lies the artwork of artist-activist Barbara Kruger. Barbara Kruger is an American conceptual artist, born in New Jersey in 1945. Her works marry graphic design, poetry, and photography to seamlessly foster a discussion on societal inequality, sexism, and women’s rights. She boasts quite the impressive graphic design journey, foraying through Condé Nast Publications and Mademoiselle magazine in the 1960s and engaging in the spheres of mass communication and media advertising before developing her own distinctive style.

Chronicling a society marked by inherent class divisions, patriarchal systems geared towards subjugation and repression of women, and a descent into rampant consumerism, Barbara Kruger rose to prominence through her sensational artwork, usually composed of a Futura Bold typeface over a red background and collaged images, with provocative political, social, or feminist text overlaid.

Chronicling a society marked by inherent class divisions, patriarchal systems geared towards subjugation and repression of women, and a descent into rampant consumerism, Barbara Kruger rose to prominence through her sensational artwork

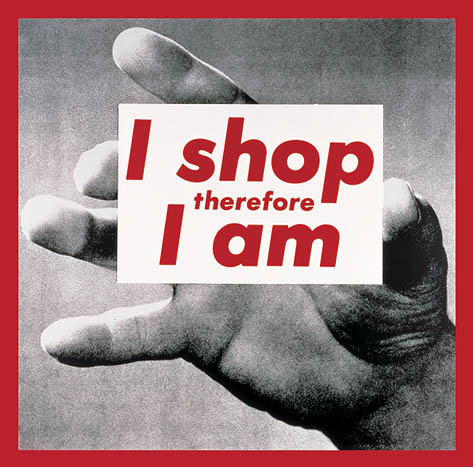

Her white-on-red type ‘Untitled (I shop therefore I am)’ (1987) is designed as a clever, incisive critique of frivolous consumerism in contemporary culture. Kruger employs black, white, and classic red to varnish the image with a retrograde aesthetic, suggesting the time-tested prevalence of over-consumption. The intertextual dialogue between Descartes’ famous declaration ‘I think, therefore I am’ and Kruger’s subversive text ‘I shop therefore I am’ offers a pointed commentary—Descartes uttered those words to prove his own existence, to create faith in the belief that one exists as a tangible vessel due to their capacity for original thought, for critical analysis, for self-determined purpose.

But Krueger’s appropriation has quite the opposite effect: rather than instilling a sense of intellectual curiosity on a quest for knowledge in a colossal Earth with colossal possibilities, it functions as a mockery, a sharp rebuke on how drastically our priorities have changed from the pursuit of creation to the trivial crusade of conspicuous consumption, which is claimed to be the only way to substantiate one’s own consciousness. It seems like now more than ever, our acquisition of consumer goods is what defines us as sentient beings.

Commodity of being: “I shop therefore I am”

‘Untitled (You are Not Yourself)’ (1982) depicts a shattered mirror reflecting the many countenances of a distressed woman. This bold artwork seems suggestive of the fragmentation of women’s identity, requiring them to adopt contradictory roles in society and subjecting them to harsh, often conflicting stereotypes. As Molly Haskel once proclaimed, ‘It was a split [between the way I saw myself… and the way I was expected to behave] that brought up to date the age-old dualism between body and soul, virgin and whore.’ As a woman looks into the reflective glass, she realises her behaviour has no bearing on her true identity after being forced to wear all the faces the patriarchal paradigm demands her to, but she knows that none of those faces are her—she is not herself. Kruger herself said in a 1991 interview that: ‘I would venture to guess that many people heed their mirrors at least five times a day and that vigilance certainly can structure physical and psychic identity.’

The famed Simone De Beauvoir quote comes to mind: ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,’ highlighting the fact that once the mirror of illusions has been fractured, gender is but a social construct. The crudely pasted letters on the surface of the mirror are jarring in comparison to the standard ‘not’ in the midst of the image—the ‘not’ presents an interjection, a warning, that regardless of the gendered hierarchy institutionally controlling the fate of women, they must snap out of their daze and take a good hard look at themselves in the mirror—even if it shatters.

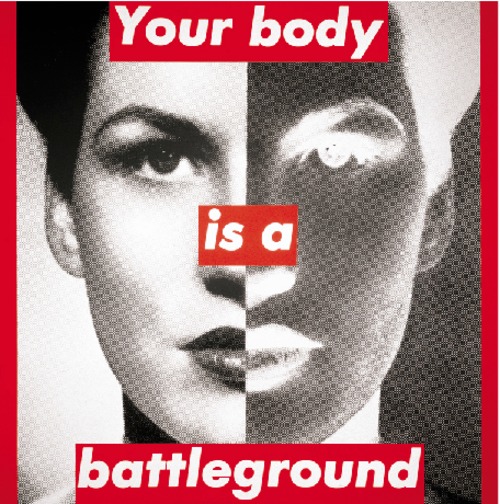

“Your body is a battleground”

‘Untitled (We don’t need another hero)’ (1987) examines another dimension of power embedded in our everyday lives—the patriarchy. Intended as a disparagement of toxic masculinity and the social construct of men as the cavalier saviours of humanity, this art piece depicts a young boy grimacing and flexing his muscles for a set of ogling female eyes and a gaping incredulous mouth.

This describes the indoctrination of the male youth into the patriarchal paradigm, revealing how boys learn to base their self-worth and social entitlement on displays of formidability and strength they believe captivate the ‘second sex’. Kruger has employed the word ‘another’, suggesting this young boy represents the countless others attempting the ordeal to achieve such narrow aspirations. The challenge—either strive to be the strongest, most valiant knight in shining armour to rescue the damsels in distress, or face irrelevance. Kruger draws attention to the futility of the all-encompassing ‘hero’, revealing the entrenchment of the gendered hierarchy in the aspirations of the youth, perpetuating the ageless cycle of subservience and domination.

Barbara Kruger’s piece ‘Untitled (Your body is a battleground)’ (1989) was created for a pro-choice Washington rally in 1989, addressing the debate over reproductive health that had culminated in a gender equality movement after the landmark 1973 Roe V Wade decision was passed in favour of the legalisation of abortion.

It depicts the symmetrical, mannequin-like face of a woman, bisected down the middle to display two halves of the same image, one positively developed and the other negatively developed. The woman embodies true conventional beauty: prominent cheekbones, perfectly shaped eyebrows, upturned eyes, fuller and luscious lips and a delicate nose that perfectly accentuates the sharp proportions of her face—she is the very picture of the beauty standard, yet this perfection becomes unsettling in its artificiality.

Through this stark imagery, Kruger declares that our bodies are ours, that we must reclaim the authority and control that men have exercised over our physical and mental autonomy. Our bodies are the macabre battlegrounds of rampant sexism. From the maternal birth-giver to the widowed sex worker, our bodies have been under institutional control from the day we emerge from the womb to the day we are lowered into our graves. This visual bifurcation suggests that women exist in a state of perpetual contradiction, never fully able to satisfy the conflicting demands placed upon them. It is an ongoing war against systems that seek to define, control, and profit from women’s bodies.