From theory to practical, gender plays a significant role in defining the methodology, message and meaning behind each lesson taught and knowledge gained in Indian classical dance.

Gender identity forms a central consideration while enrolling to pursue a ‘co-curricular activity’ in a country chronically preoccupied with academic achievement. Gender hence, influences the choice of the activity, art form, guru, their teaching style, relationship with students and social perception by the society.

Indian classical dance forms have been shaped by many mythological stories, folklore, religious customs, and beliefs which portray an intersection of gender and aesthetic narratives. Like every cultural practice in India, it is not insulated from caste and class politics.

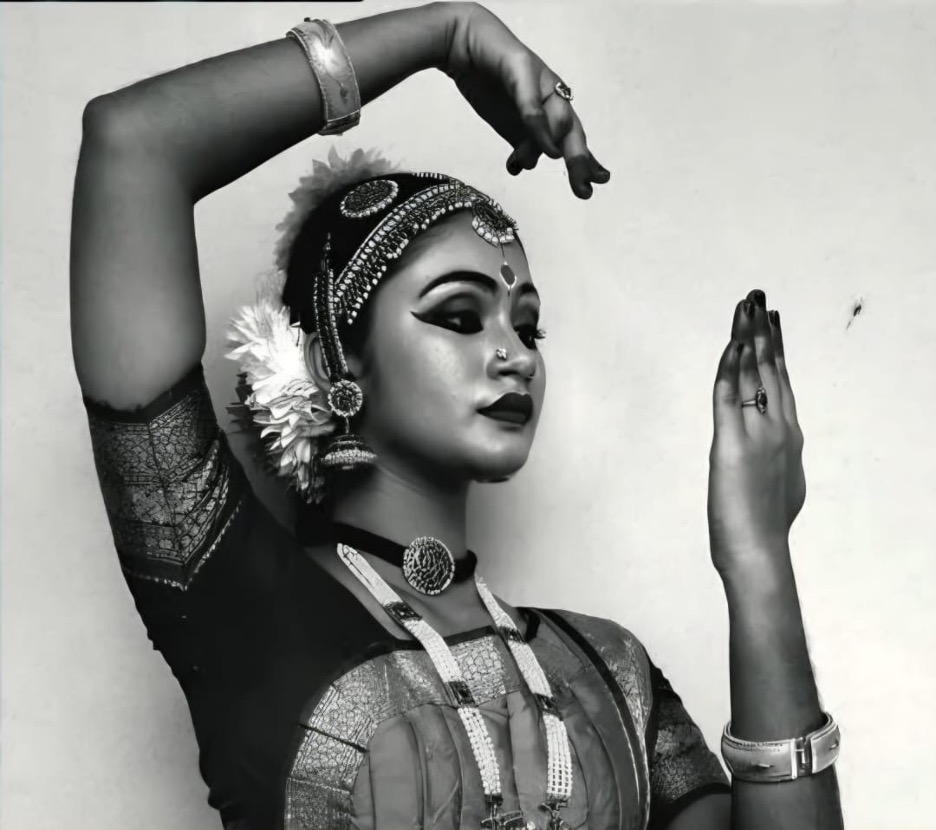

Credits: Digital Shivam Studios

This article compiles perspectives of young and trained female artists from across six Indian classical dance forms. They examine how gender-identity shapes their daily practice, stage performances and established norms of teaching, training and learning ancient artforms in modernising times.

Choice, chance or challenge?

For women in India dance is an assumption, expectation, inheritance, discipline and/or control before being introduced as a form of expression. The stereotypical understanding of women naturally embodying fluidity in movement, restraint and rhythm encourages elders to enroll girls in dance schools. However, this is selective. There is a caste-class hierarchy within the Indian dancing traditions which privileges classical dance over folk, regional and western dance forms. An invisible boundary is created when Bharatnatyam, Odissi, Kathak, Mohiniyattam, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, Manipuri and Sattriya, the eight recognised Indian classical dance forms, are chosen as acceptable ‘activities’ that daughters can participate in as against non-Sanskritised traditions. Dance as a tool of social stratification reinforces regulation, bound decorum and tool for upward social networking.

Aswaty, a Bharatnatyam dancer who began training at the age of 9 commented upon her gender identity in influencing the choice of artform, “Definitely! It is common practice among South Indian girls to start dancing and training at very young ages. It is rarer in Christian families (I am Christian) but still pretty prevalent.” But today, she added, “Dance is a space where I can ‘perform’ my femininity with confidence.” Another Bharatnatyam dancer, Srinidhi saw dance as an opportunity to break the monotony of professional pursuits and take the challenge to stand out.

But while passion or will to continue the lineage were some motivations, Aastha shared how Bharatnatyam was chosen for her eleven years ago to develop “feminine discipline” or curb the masculine ways in which she expressed herself. “As a woman, dance was chosen for me so that I could develop grace, discipline, which are stereotypical feminine virtues and so that it adds value to me as a woman.“

Male and transgender dancers are often denied formal training and instead seek peer or online sources, depriving them of the ‘trained’ certification. Social stigma and systematic exclusion makes finding gurus (teachers) a struggle for transgender individuals. Though transgender people have been associated with dramatic and exaggerated dancing styles, in India, transgender folk dancers have brought regional forms to national prominence. Bharatnatyam has also been particularly inclusive of transgender artists.

Classical dancing is not considered a masculine pursuit and this discourages men to explore it altogether. If allowed to, the choice of dance form is determined in accordance to gender identity. The association of classical dancing with femininity and western styles with masculinity are stereotypes common to cultures globally. This shows how alignment of a co-curricular endeavour with gendered norms influences the accepted form of expression.

The Test of Gender Inclusivity

Indian classical dance forms have historically been a genesis of Tandava and Laasya, the masculine and feminine embodiment of bodily expression. Srinidhi, a Bharatnatyam dancer elaborated on the folklore of ‘Ardhanarishvara’, mentions how her artform represents the concept of gender. According to this, Hindu God Shiva and his consort, Goddess Parvati merge into one body, split vertically down the middle. Shiva is considered the ‘Lord of Dance’ who performs Tandava in his Nataraj form and to balance his vigorous energy, Goddess Parvati does Laasya, a style incorporating grace, elegance and beauty into its movements. However, this was not a strict demarcation on who can perform the respective styles of dance. Within this binary several Indian classical and folk dance forms emerged and often transpired to represent both the dynamic energies. Manza, training in various Indian dance forms for the past 12 years, explains this as, “gender balance, coexistence, and the idea that masculinity and femininity are complementary rather than binary.”

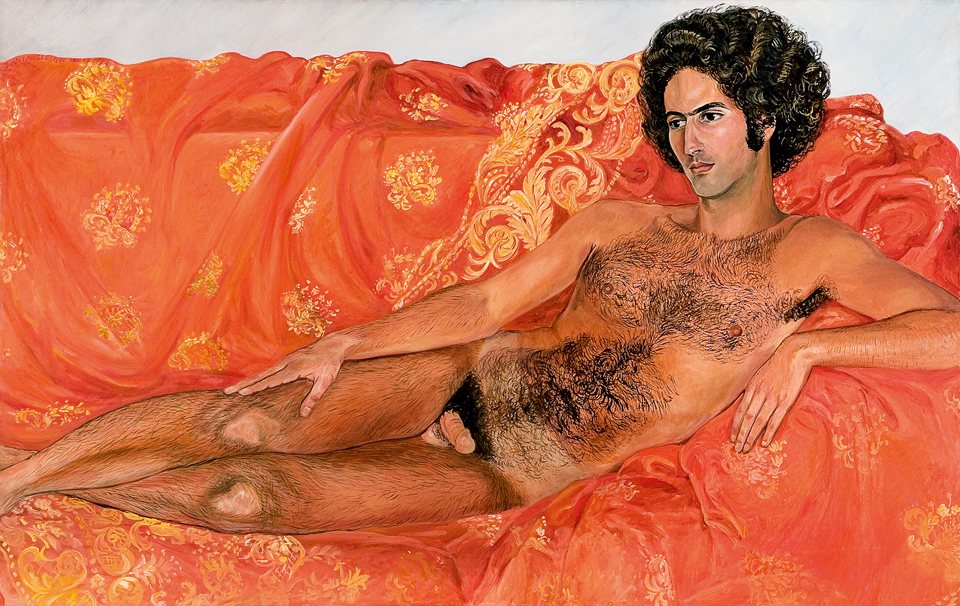

Credit: Universal Rasikaas

Classical dance forms are distinct because they are rule-abiding, based on precise form and technique. But while ancient origins solidify the belief of historical gender fluidity of engaging in art, the past may prevent progress in the present. Srinidhi believes, “Performing arts is the only medium where the artists are not judged based on their gender but their talent.” She adds, “Even the lord himself is a male dancer, the book that teaches us what audio visual communication is was written by a male sage. So, I don’t think gender was ever the issue. It was the society that brought these differences.”

The historical origins of performing arts in India is traced to the 2nd century AD when the Abhinaya Darpana and Natyashashtra were written by Sages Nandikesvara and Bharata Muni respectively. These codify the ‘Guru-Shishya Parampara’ (teacher-disciple lineage) and provide a grammar of postures, gestures, footwork and body movements. Fascinatingly, it does not bound movement to gender identity. While modes of movement may be based on energies, the classical dancing body is the ‘Ardhanarishwara’ or asexual entity which creates a transcendental experience beyond gender. Srinidhi says, “I believe that the dancer in a single Shloka (verse), must instantly switch their body’s posture. One half of the body might perform the fierce movements of Shiva, while the other simultaneously maintains the soft, rounded gestures of Parvati.” This, according to her, has been identified by queer practitioners as a divine precedent for non-binary identity.

Interviewees saw present practices of Indian classical dancing as being largely gender-neutral because narration is not included in performances and the costume, posture and choreography are mediums of conveying bhava (emotions) to the audience. Hence, versatility in thought and movement is what classical dancers spend years mastering.

Ashwini, a disciple of Padma Shri Guru Malti Shyam and a guru herself, talked about how even if perfection cannot be achieved in cross-gender representation, the attempt itself enhances the value of the performance. Akshita, an Odissi dancer, mentioned the tradition of ‘Gotipua‘, where males dress up as females. She gave the example of Guru Kelucharan Mohaia who was a Gotipua and is considered as the architect of modern Odissi. Even as Bharatnatyam is preferred to be learnt from a female teacher Srinidhi gives the example of her guru, Karnataka Kalashree Dr Sathyanarayana Raju as a male exponent who has mastered the Saathvika Bhava, traditionally associated with women, to say, “He is someone every female artist in the country envies.”

However, literature can both liberate and limit. Manza talked about the mythological origins of Mohiniyattam being gender-specific. Being made for women or ‘Mohinis’ she says that, “The norm itself states its for women and therefore the artform is known for Laasya and feminine movements and grace so most of the men won’t prefer.”

Yet, Niranjhana, in her 17 years of training in dance forms including Mohiniyattam, has accepted that as an artist one must move to space where the external appearance does not matter and the dancer must be the character at the given moment. She strongly asserted, “I believe we are all gender-neutral and if we are assigned a certain gender then it is our choice to take up the role or not.”

Aswaty looks at dance as a created space which is not sheltered from patriarchy. This space includes not just the dancers but also musicians, make-up artists etc. Manza shared how accompaniments like nattuvangam and percussion were male-dominated domains, while women were more visible as performers. Aastha has observed the tabla, mridangam, flute and keyboard being mostly played by men. However, Ashwini also shared how a component of the syllabus that she teaches to final year Kathak students requires them to learn at least one instrument. With evolving times, many female exponents are defying centuries old stereotypes and skepticism about a woman’s ability to master cumbrous instruments.

Responding to change with reform

Interviewees were in a consensus on how the ‘Ardhanarishwara‘ tradition has affected a gender-neutral learning environment. However, when it came to performances, tokenistic representation to “put up a show” was prioritised over principles and practice. Khooshi, an Odissi dancer shared, “A lot of times females are just expected to be good at dancing mostly while if a male knows even some basic steps they are applauded more or appreciated more.” As a non-believer in the concept of gender, especially in dance, Niranjhana also finds the preference given to males troubling when the effort put is equal. “All I want to change is the demand and supply. We go through the same blood, sweat, tears and years of training,” she said.

Alternatively, Akshita pointed out how not in the dance form but in the larger society, “People look down and question a man’s character if he learns classical dance.”

Finally, when asked about which gender-related practice they wish to reform, dancers had multiple suggestions. Aastha raised the common concern of how people believe that dance changes the body of men to less masculine. She mentioned the historical association between Bharatnatyam and prostitution stemming from misguided constructs to Sanskritise the Devadasis tradition. Modern critiques emphasize on how the 20th century appropriation of the original Bharatnatyam traditions such as the Isai Vellalar and Devdasis, by elite Brahman performers was an attempt to rebrand it as ‘spiritual’ or ‘pure’, while shaming the original dancers who performed in temples. Aastha blamed this for having limited the showcase of interaction between gender, sex, and sexuality. She wishes to, “Regain the rawness when it comes to how blunt it is depicting controversial topics like these.”

While Akshita strives to reform the practice of gender essentialism and rigid role assignments in Odissi, Khooshi hopes to create a learning space which sets equal benchmarks for men and women. As a Kathak guru, Ashwini aims to normalise male dancers performing the role of female goddesses and foster a fluid learning environment that she experienced growing up.

Niranjhana sees Indian classical dance as an excellent tool to sensitise the elderly on topics related to gender justice and rights as in this modernising age, it is a traditional medium that continues to command immense respect among them. These observations, insights and suggestions from contemporary practitioners of ancient artforms is a reassurance that tradition is not an impediment to transition, but an opportunity to leave no one behind.

Aparna is a Visharad Poorna diploma holder in Kathak from ABGMV under the discipleship of Guru Ashwini Soni.

About the author(s)

Second year student of Media Studies at CHRIST (Deemed to be University), BRC, Bangalore. A trained Kathak dancer, theatre artist and political nerd.