Art has long been intertwined with political protest. Artistic expressions have always been an effective way in which dissent has been expressed through revolutionary posters and protest songs, as well as through murals and street performances, which have also been used to assert identities as well as to criticize the dominant narratives. In contexts of conflict and repression, where formal political participation is constrained or rendered dangerous, art often becomes one of the few available languages of resistance. Graffiti is one of the several types of protest art that take a rather precarious yet powerful stance. Produced in the street, graffiti is usually created illegally and anonymously, disrupting everyday visual landscapes and forcing political questions into spaces where they are meant to be absent.

The contested region of Kashmir provides us a compelling site to study the connection between art and political protest. Kashmir’s public spaces have long been deeply regulated and contested, marked by decades of militarization, surveillance and political uncertainty. However, it is in this highly policed setting that graffiti has developed as a visual fighting means. Kashmiri graffiti painted on the walls, shutters, bridges, and in the alleyways talks of loss, longing, anger, solidarity, and defiance. It turns the regular city streets into platforms of political communication, memory, and protest.

The contested region of Kashmir provides us a compelling site to study the connection between art and political protest. Kashmir’s public spaces have long been deeply regulated and contested, marked by decades of militarization, surveillance and political uncertainty.

Graffiti in Kashmir has long been an effective form of protest art and visual politics. Graffiti is not only an aesthetic art practice but also a political action that disrupts mainstream discourse, gives voice to marginalized people, and helps in the formation of a shared memory.

Art, protest, and the politics of visibility

Political protest is not only enacted through marches, slogans, or institutional resistance; it is also deeply visual. Protest movements base their grievance on symbols, images and performances to render it legible. Art is an essential part of this process as it determines the way in which political struggles are perceived, experienced and recalled. Images, as theoreticians of visual politics have maintained, do not simply reflect political realities but rather actively make up politics by providing frames to what is visible and what is not visible.

Specifically, graffiti works at the nexus of art and protest. The product of urban subcultures and typically linked to marginality, graffiti disrupts the law, property, and order. Its placement in public spaces ensures that political messages cannot be easily ignored. In contrast to gallery art or the institutionalised cultural production, graffiti literally confronts the people passing by, disrupting the visual habits of normal life.

In protest contexts, graffiti serves several political functions. It allows for anonymity in repressive environments, allowing artists to register their protest without identification. It creates collective authorship, whereby walls are used as common canvases where voices are developed by different individuals over a period of time. It also establishes a counter-archive of political articulation, storing the feelings and experiences that are frequently lost in official histories. These features render graffiti particularly important in conflict areas, where power over discourse and publicity is intensively fought.

Kashmir as a contested visual space

The political struggle in Kashmir is terrestrial as well as diplomatic, but also very visual. The landscapes of the region are flooded with the artifacts of state power, such as military bunkers, checkpoints, surveillance cameras, along with barbed wire and carefully curated images of normalcy and tourism. This visual order is aimed at disciplining the public space and controlling political expression. In such a setting, visual dissent is both risky and radical.

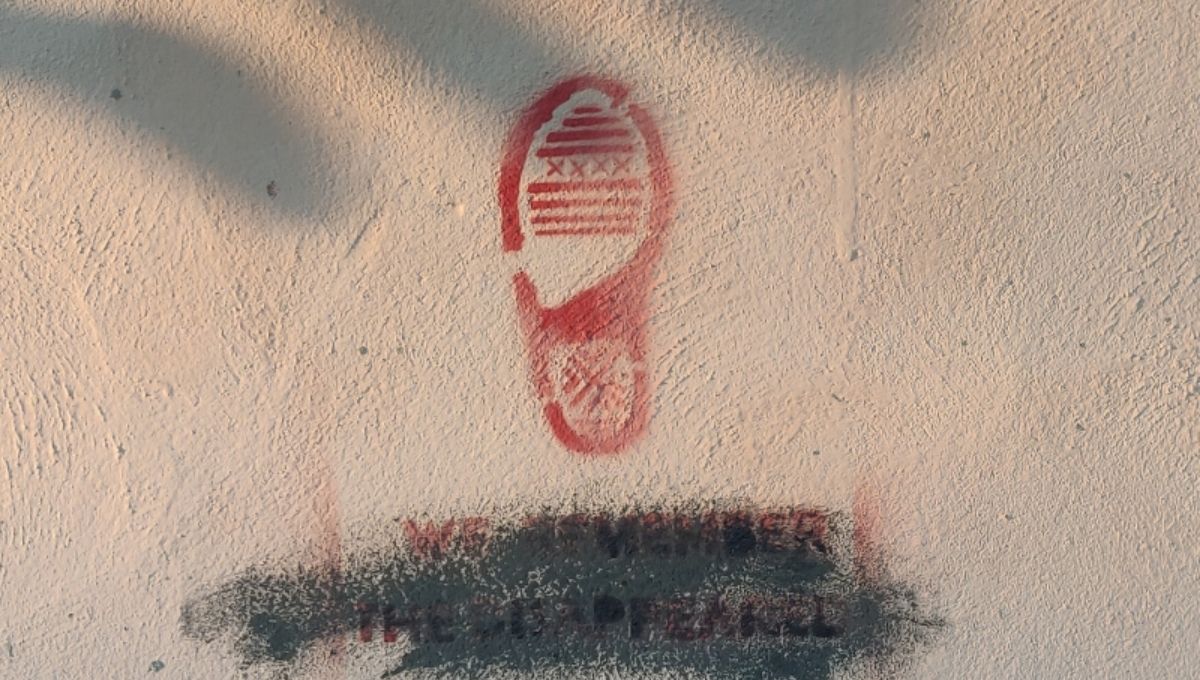

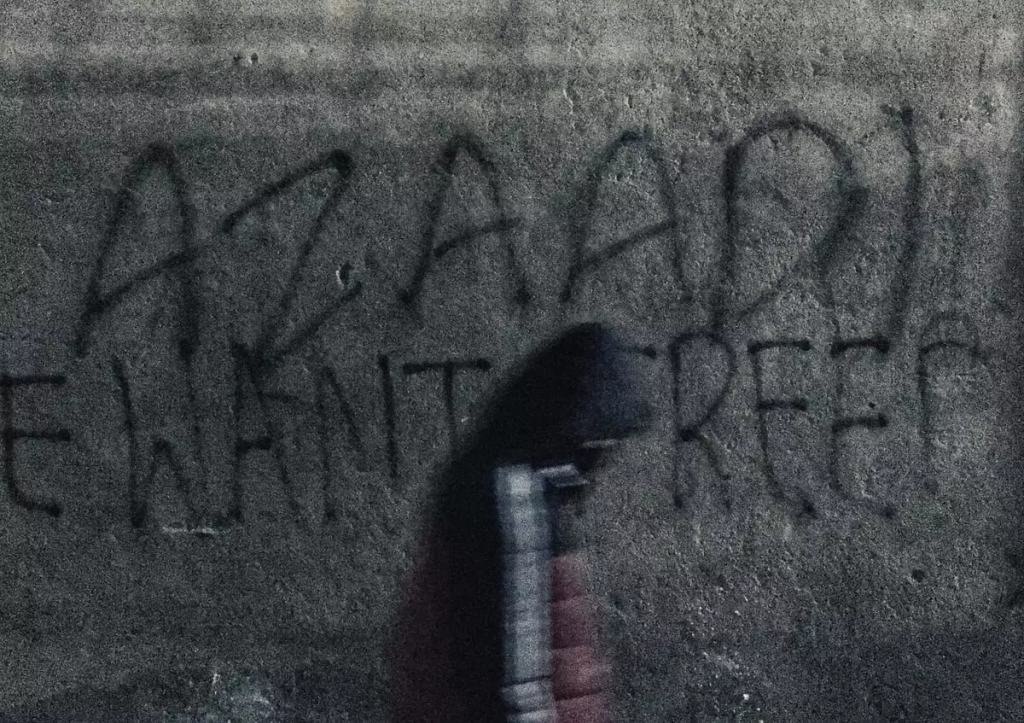

Graffiti in Kashmir began to gain prominence in the late 2000s, particularly during periods of mass protest. The initial messages of the graffiti, such as “azaadi” (freedom) and “free Kashmir” were written on roadside walls and street lanes, marking a shift in how political sentiments were publicly expressed (Amin and Majid, 2018, p. 63). As time passed, graffiti evolved in style and content and adopted stencils, murals, and symbolic imagery, inspired by global resistance art, including Palestinian street art.

There is something unique in Kashmiri graffiti that makes it protest art: its integration in daily life. Also, unlike organized protests, which are usually met with force, graffiti subtly takes up the space at night and is found unexpectedly in the morning. It uses a visual language, which is accessible, instantaneous, and emotionally alert. In doing so, it reclaims public space from state narratives and reasserts the presence of dissenting voices.

Graffiti, disappearance, and collective memory

The issue of forced disappearance is one of the most painful themes of Kashmiri protest art. The course of the conflict has seen the disappearance of thousands of people across religious and social backgrounds, leaving families distraught. Such disappearances are not visible or are minimized in official accounts, which makes them hidden in official political discourse.

Graffiti intervenes in this erasure by making absence visible. Murals depicting disappeared persons, symbolic imagery of eyes, faces, or clocks frozen in time, and textual references to loss and waiting to transform walls into sites of mourning and remembrance. These visual interventions can be described as a sort of “counter-memorials” which disrupts the state’s control over the historical narrative and demands that unresolved trauma be addressed.

In this regard, graffiti helps to build collective memory. It brings into the open the privateness of grief, making personal experiences of loss be recognised as political. Such images reproduced in different neighborhoods form a common vocabulary of remembering, developing resistance, and asserting their right to their and justice. Art in this case is not only cathartic but also political, as it demands recognition in an environment where they are expected to remain quiet.

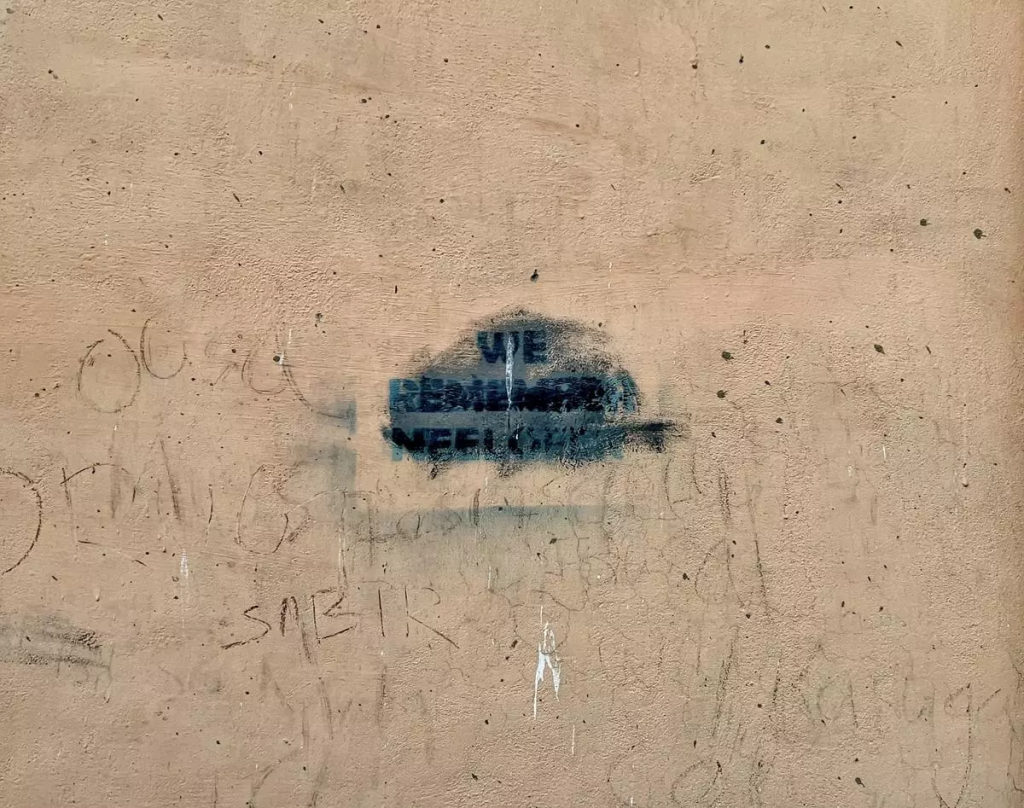

A blackened “We remember Neelofar” graffiti in Lalchowk, Srinagar, on the wall of a government building. It refers to the Shopian rape and murder case, also known as the Asiya-Neelofar case, in which two young women were abducted, raped and murdered, allegedly by personnel of the Indian Army, in 2009 in Jammu and Kashmir’s Shopian district.

Youth, risk, and the politics of creation

In Kashmir graffiti is mostly youth-led since artistic protest is a source of both an outlet and a form of political participation. Painting graffiti in a militarized environment involves significant risk. Artists usually paint at night, aware of the fact that they are always on the watch and risk being met with arrest or violence. The danger imbues the act itself with political meaning. The process of creation becomes a performance of resistance, not just the final image.

For many young artists, graffiti provides a combination of art and activism. Some view their work as a documentation of some kind, others as an emotional outburst, and others as direct political intervention. Such ambiguity breaks down strict definitions of protest art. Graffiti in Kashmir cannot be easily separated into “aesthetic” and “political” domains; it exists precisely in their overlap.

Further, Kashmiri graffiti has been used to convey the support of world causes, especially Palestine. Slogans like “Free Palestine, Free Kashmir,” and adaptations of international protest art put the local conflict within a broader transnational framework of resistance. This visual solidarity highlights the fact that protest art cuts across international boundaries and establishes shared languages of dissent, which links divergent struggles against occupation, repression, and marginalization.

Political protest art is not decorative or symbolic; it is constitutive of political struggle. Kashmiri graffiti and graffiti art in general are examples of ways visual art may serve as resistance, memory and political communication in contexts of conflict. Graffiti challenges the mainstream narratives and restores visibility to oppressed voices through its occupancy in the public space, with its engagement with themes of disappearance and solidarity, and its provocative production processes.

By situating Kashmiri graffiti within broader debates on visual politics and protest art, this essay highlights the importance of taking aesthetic practices seriously in the study of political conflict. Graffiti teaches us the idea that resistance is not necessarily loud or institutionalized, but sometimes it sits quietly on the walls and demands to be noticed. In contested spaces like Kashmir, such acts of visual protest are not just expressions of dissent; they are assertions of existence, memory, and political aspirations.

Bibliography:

A.K, A. (2024). Envisioning Kashmir’s Future through Paint and Verse. [online] Hyperallergic. Available at: https://hyperallergic.com/875314/envisioning-kashmir-future-through-paint-verse-masood-hussain-gabriel-rosenstock/.

Abel, E.L. and Buckley, B.E. (1977). The Handwriting on the Wall. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Ahmad, G. (2021). Kashmiri Artist Arrested over ‘We Are Palestine’ Graffiti. [online] The Cognate. Available at: https://thecognate.com/kashmiri-artist-arrested-over-we-are-palestine-graffiti/.

Amin, M. and Majid, I. (2018). Politicising the Street Graffiti in Kashmir. Economic and Political Weekly, 53(14), pp.61–66.

Bleiker, R. (2009). Aesthetics and World Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bleiker, R. (2018). Visual Global Politics. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, Ny: Routledge.

Bleiker, R. (2021). Seeing beyond disciplines: Aesthetic Creativity in International Theory. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 75(6), pp.573–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2021.1992129.

Bleiker, R. (2023). Visualizing International relations: Challenges and Opportunities in an Emerging Research Field. Journal of visual political communication, 10(1), pp.17–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jvpc_00022_1.

Callahan, W.A. (2020). Sensible Politics : Visualizing International Relations. New York, Ny: Oxford University Press.

Ganie, M.T. (2022a). Claiming the Streets: Political Resistance among Kashmiri Youth. In: Routledge Handbook of Critical Kashmir Studies. Taylor & Francis.

Ganie, M.T. (2022b). Conflict and Narratives of Hope: a Study of Youth Discourses in Kashmir. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 33(1), pp.115–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/isia.2022.0028.

H, S. (2021). A Look at Some of the Brilliant Resistance Art Coming out of Kashmir. [online] Homegrown. Available at: https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-voices/a-look-at-some-of-the-brilliant-resistance-art-coming-out-of-kashmir.

Ibrahim Fraihat and Hamid Dabashi (2023). Resisting subjugation: Palestinian Graffiti on the Israeli Apartheid Wall. Ethnic and Racial Studies, pp.1–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2247473.

Kanjwal, H., Bhat, D. and Zahra, M. (2018). ‘Protest’ Photography in Kashmir: between Resistance and Resilience. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46(3-4), pp.85–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0033.

Khan, F.L. (2022). Tracking Kashmiri Politics via Graffiti in Srinagar. [online] Paper Planes. Available at: https://www.joinpaperplanes.com/tracking-kashmiri-politics-via-graffiti-in-srinagar/.

Lisle, D. (2006). Local Symbols, Global Networks: Rereading the Murals of Belfast. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 31(1), pp.27–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100102.

Maqbool, M. (2016). The Writing on the Walls in Kashmir. [online] thewire.in. Available at: https://thewire.in/politics/kashmir-graffiti.

Maqbool, R. (2015). Murals Celebrating Local Culture Are Derided as Censorship in Indian-administered Kashmir. [online] Global Press Journal. Available at: https://globalpressjournal.com/asia/indian-administered_kashmir/in-kashmir-murals-celebrating-local-culture-are-derided-as-censorship/.

McAuliffe, C. (2016). Young People and the Spatial Politics of Graffiti Writing. In: Identities and Subjectivities. Singapore: Springer Reference.

Miladi, N. (2015). Alternative Fabrics of hegemony: City Squares and Street Graffiti as Sites of Resistance and Interactive Communication Flow. Journal of African Media Studies, 7(2), pp.129–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jams.7.2.129_1.

Miladi, N. (2018). Urban graffiti, Political Activism and Resistance. In: The Routledge Companion to Media and Activism. Routledge, pp.241–247.

Naqash, R. (2016). Writing on the wall: in Kashmir, Graffiti Meets Counter Graffiti. [online] Scroll.in. Available at: https://scroll.in/magazine/816041/writing-on-the-wall-in-kashmir-graffiti-meets-counter-graffiti.

Rather, M.K. and Bhat, B.G. (2013). POETS OF KASHMIR: A DIGITAL LIBRARY. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), [online] p.1. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280048776_POETS_OF_KASHMIR_A_DIGITAL_LIBRARY [Accessed 6 Jun. 2024].

Riza, M.W. & H. (2022). Walls of Defiance in Downtown Srinagar. [online] Frontline. Available at: https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/photo-essay-walls-of-defiance-graffiti-in-downtown-srinagar/article66274485.ece.

Roth, D. (2014). Vigils and Vandalism: How Hong Kong’s Graffiti Artists Can Help Us Understand the Protesters. [online] International Policy Digest. Available at: https://intpolicydigest.org/vigils-vandalism-hong-kong-s-graffiti-artists-can-help-us-understand-protesters/#google_vignette.

Saha, A. (2016). Writing Is on the Wall in Kashmir: Graffiti Takes Political Colour. [online] Hindustan Times. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/writing-is-on-the-wall-in-kashmir-graffiti-takes-political-colour/story-8AmzUhXOf3cKZtmqLgOSGK.html.

Taş, H. (2017). Street Arts of Resistance in Tahrir and Gezi. Middle Eastern Studies, 53(5), pp.802–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2017.1299007.

About the author(s)

Sahil is an India Fellow working with Aajeevika Bureau, where he focuses on promoting labor rights and raising awareness among migrant workers. His work includes conducting sessions on occupational safety, workplace rights, and the importance of collectivization. He also facilitates discussions on issues such as wage stagnation, workplace hazards, and legal redressal mechanisms, empowering workers to advocate for their rights and improve their working conditions.