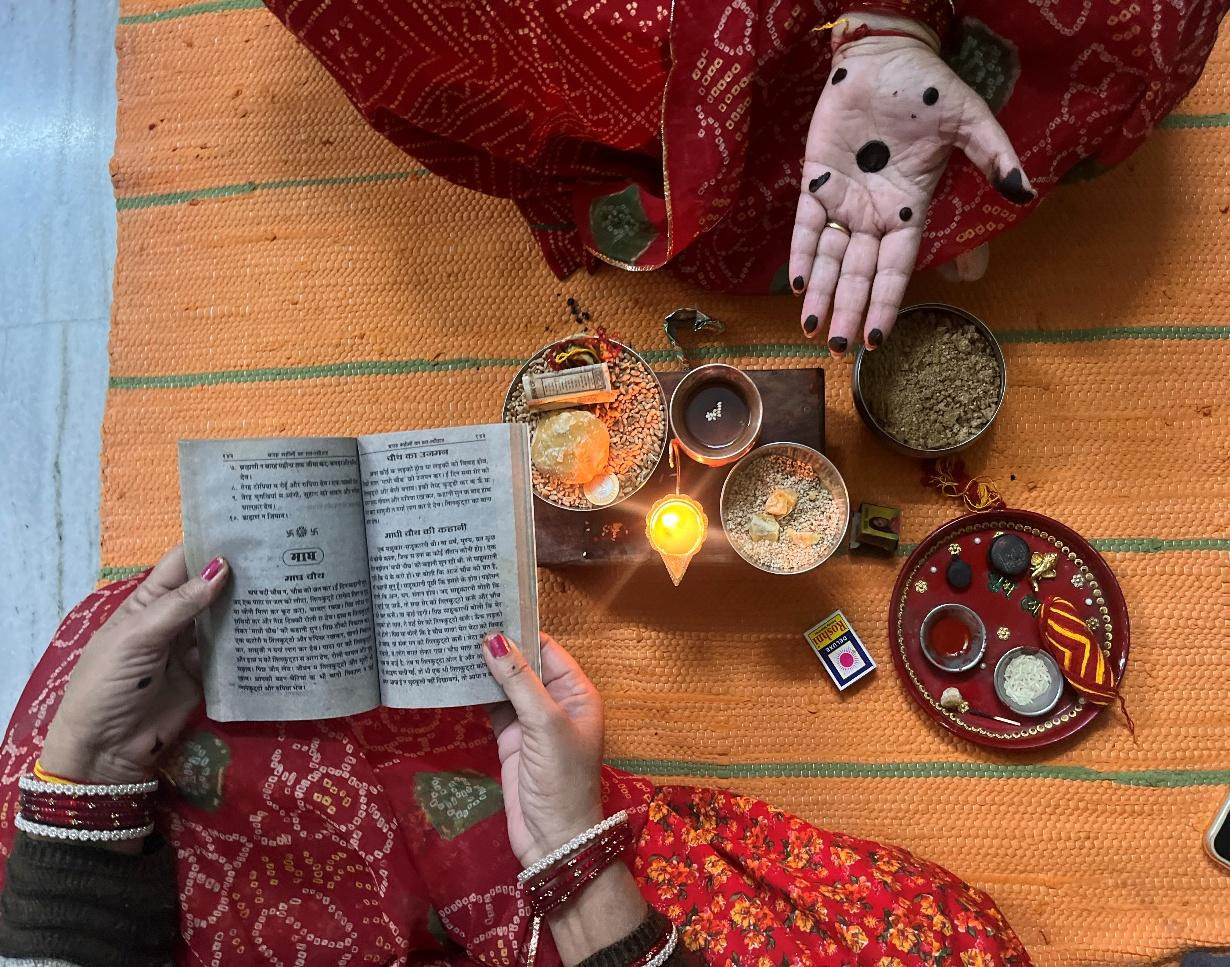

A group of Rajput women gather in a household to observe a fast, holding sesame seeds mixed with jaggery close to their hearts as they wait. They are seated in a loose circle and all eyes are on the eldest woman of the household, who is guiding the youngest daughter-in-law, on how to find the ‘Tilkuta Chauth ki kahani’. The young woman turns the pages of a yellow book that purports to contain vrat kathas for almost every festival in the Hindu calendar, all in 200 pages. Her fingers are moving quickly, almost anxiously, as the diya placed on a heap of wheat grains can only be lit once the story is found.

Meanwhile, around her, women apply mehendi (henna) to their hands, stroke kajal (eyeliner) into their eyelids, and apply tilak to each other’s foreheads. They act in practised precision, each making sure they have the right red bangles in their hands, toe rings checked, adjusting their chunri (scarf), touching all symbols of suhag (wifehood) briefly as if to confirm their presence. Before the storytelling begins, all of them visually assert their suhagan (married) status through what can be understood as ritual markings.

When the story is found, the diya is lit, and the woman with the book begins to read in a slightly raised voice. Her voice carries the authority of repetition momentarily, but she loses that privilege as soon as the ritual ends. “Padhi likhi hai par iski awaj bas yahin sunti hai, baaki chup rehti hai bhut sanskaari hai (She is educated, but she only speaks in spaces like this. Otherwise, she remains silent as she is well-mannered),” her mother-in-law, Saroj Kanwar, remarked. As the story unfolds, each woman present listens carefully. The other women do not remain silent but murmur “hmm….hmm….” as if confirming the narrative, thereby making the katha a shared performance.

Ritual and the Sacred Meaning

This murmured assent to the narrative signals agreement, recognition and belief. A newly married Rajput woman, Ranjana Rathore, who regularly observes the vrat (fast), said, “Shuru mein mushkil lagta hai, phir aadat ho jaati hai. Vrat na rakho toh kuch adhoora sa lagta hai (At first it felt difficult, then it became a habit. If you don’t keep the fast, something feels incomplete).” The women are seated with empty stomachs, but their bodies are disciplined. The story proceeds not only through voice but also through the hands that hold grains, eyes lowered in concentration, and lips murmuring the ritualistic sounds of approval. The vrat and the ritual storytelling are tightly woven together. The vrat katha functions as a form of ritual art, performed, repeated, and aesthetically framed, through which social norms are not merely transmitted but also transformed into sacred meaning.

The vrat katha is more than religious storytelling; it becomes a medium through which the women involved make sense of their worlds and of what constitutes virtue, duty, and devotion. As Clifford Geertz argues, religion works by surrounding everyday lives with ‘an aura of factuality.’ The repeated telling of vrat kathas, the endurance of hunger, and obedience are not seen by women as enforced, but as meaningful acts that feel right, familiar, and morally valued.

The Ritual Architecture of Devotion

During the vrat katha ritual, domestic spaces that house these women are temporarily transformed into sites of collective worship. The yellow book is itself revered and placed alongside other deities in the household, even when not in use. In this way, the book itself carries symbolic significance. An elderly woman, Lakshmi Kanwar, said, “Yeh ek dharmic kitaab hai, iska rang hamare dharam me bhut mahatava rakhta hai (This is a religious book, and even its colour holds great importance in our faith).”

Vrat kathas shape how devotion is felt, how womanhood is learned, and how life itself is organised and gets embedded in the very texture of lived experience.

Women’s bodies are marked by hunger as they do not even drink a sip of water before listening to the vrat katha, thereby rendering the body itself a site of devotional labour. Vrat kathas shape how devotion is felt, how womanhood is learned, and how life itself is organised and gets embedded in the very texture of lived experience.

Glorifying Suffering, Sanctifying Sacrifice

Almost every vrat katha from the book follows a predictable structure. It begins with a woman facing suffering or crisis, who then undertakes a vrat with complete devotion in the name of the goddess designated for that vrat. Her sacrifice is tested through escalating trials, and she is painted as the epitome of an ideal woman throughout the story. Finally, her unwavering faith is rewarded through divine intervention when the goddess herself appears before her and grants her wishes. The most striking feature of the reward is that it almost always takes the form of male well-being, while in one vrat katha, a husband’s life is saved, in another, a son is born after many daughters, some stories end with protecting the male child from serious illness, and a few are specifically to secure a brother’s prosperity.

The narratives within vrat kathas are all tied to a single thread and remarkably consistent in their ideological apparatus. An ideal of womanhood is constructed through these vrat kathas, which portray the ideal woman as one who masters self-denial, silent suffering, and ultimate devotion to male family members. When asked whether vrat kathas feel unfair to women, a group of women responded almost in unison, “Aurat ka kaam dena hota hai, lena toh ghar ke mardon ka bhagya hota hai (A woman’s role is to give, while receiving is the fate of the men in the household).” The vrat kathas are distinct from other religious narratives in their modus operandi, as they explicitly function as tools to discipline women who listen to them. They cannot be reduced to mere storytelling, as they serve a larger purpose of teaching women that suffering is expected and necessary. A woman’s spiritual merit depends on how much pain and hardship she is willing to silently endure for the sake of men and familial welfare. Her body becomes a site of ritual suffering, and it is shown as belonging to others.

Sustaining Caste and Patriarchy

These kathas emerge from and are most strictly observed within caste settings, where women’s bodies bear the burden of preserving family honour, lineage, and social standing. Sajjan Singh, a local leader, remarked, “Hamare yahan auratein hi ghar ki izzat hoti hain (In households like ours, women carry the honour of the family).” In such households, a woman’s fasting, restraint, and devotion are closely watched and valued as signs of respectability. Ritual practice thus serves to maintain not only faith but also the caste order itself.

The valourisation of suffering amongst women is sustained through a logic of exchange. They imbibe this logic of transactional devotion, which suggests that fasting and denying themselves food can earn them divine blessings.

The valourisation of suffering amongst women is sustained through a logic of exchange. They imbibe this logic of transactional devotion, which suggests that fasting and denying themselves food can earn them divine blessings. Rama Kanwar, who works as a primary school teacher, quietly said, “Hum bhookhe rahenge tabhi pati aur bachchon ka bhala hoga (Only if we remain hungry will our husbands and children be well).” The blessings rarely benefit them directly, often manifesting as male protection, prosperity, or progeny. Women’s bodies become currencies in an economy of sacred obligation; their suffering is the price paid for rewards that mostly go to men. This ritual act of vrat katha thus naturalises patriarchal logic, and women start to feel normal and even sacred. Through vrat katha narratives, women are taught to endure suffering, whereas their male counterparts are granted power and protection as divine blessings.

A Feminist Intervention

Today, Indian public discourse is filled with debates on women’s autonomy, bodily labour, and consent. Vrat katha, as a ritual art of storytelling, also deserves closer feminist attention. They reveal the dilemma of identifying gender-based violence as merely a covert form of violence. What vrat kathas represent is a deeply ingrained form of violence that is intimate in nature rather than public, and it is sanctified rather than being criminalised. This is a form of violence that women themselves perform on their own bodies. Love and devotion act as a medium of this violence, masking it as agency and choice.

Feminist analysis of religion must be wide and sensitive enough to respect the lived realities of women, while also being brave enough to question the social and cultural systems that produce them.

Feminist critique of everyday religious practices is often met with defensiveness. When asked regarding the misogynistic tendencies of vrat kathas, Payal Kanwar, who is a graduate, said, “Yeh toh hamari marzi hai, ismein koi zabardasti nahi hai (This is our choice and there is no force involved).” Another woman Surgyan Kanwar asked, “Yeh parampara hai, ispe sawal kyun uthana? (It’s a tradition, why question it?).” The argument is that a woman’s religious expression should be respected as either a cultural tradition or a personal choice. However, the question is whether such a choice can exist in isolation. When girls grow up, they hear and imbibe stories that equate the worth of married women with self-erasure, and communities valorise women’s suffering as some sort of spiritual achievement. Yearly fasting cycles are structured around the deprivation of female bodies for male benefit. Thus, it is not the terrain of free choice but of deeply sedimented power.

The point is not to shame women who observe vrat and partake in vrat katha rituals. The point is to insist that two truths exist simultaneously. One, that women’s religious practices are meaningful to them, and that those same practices can reproduce their subordination. Feminist analysis must be wide and sensitive enough to respect the lived realities of women, while also being brave enough to question the social and cultural systems that produce them.

Conclusion: Sanctified Subjugation

Women are not only participants but also the strongest enforcers and most devoted practitioners of vrat katha rituals. This cannot be dismissed as blind belief, nor can it be termed as simple victimhood. It is the complex reality of Indian societies where power often operates through culture. For many women, especially in upper-caste households, where honour, purity, and lineage carry weight, these rituals offer a sense of belonging, moral clarity, and purpose. In this way, women become active participants in their own subordination because patriarchy is not only coercive but also seductive in nature.

Ritual storytelling transforms patriarchal norms into sacred duties. It shows how gendered power works best when it feels like devotion rather than control, when it is performed collectively rather than imposed, when it speaks in the language of gods and goddesses instead of the authority of law. The need of the hour is to pay attention to these intimate cultural spaces where obedience to patriarchal ideals is learned softly through faith and affection.

About the author(s)

Gunjan Shekhawat is a final-year PhD Candidate at the Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her working thesis is titled, “Becoming Sati: Ritualisation of Violence amongst Rajput Women of Shekhawati Region in Independent India.” She is experienced in ethnographic research, and her research interests include Feminist Theory, Political Anthropology, Political Culture, and Ritual Studies.

You’ve expressed this topic so well, the story writing skills are amazing. The research is so detailed that it answers most of the questions coming in my mind along with making it feel like being a live viewer of the research. Keep it up ma’am.