There is something deeply unsettling about how girls go missing in India. Children disappear from neighbourhoods, official records, and eventually from public memory, with alarming ease. Their absence rarely produces urgency; instead, it dissolves quietly into paperwork, where lives are reduced to statistics. They are reduced to single digits in the ever-growing register of missing children.

Mardaani 3 enters this uneasy terrain with apparent intent, choosing the trafficking of pre-pubescent girls as its central concern. The subject matter is undeniably grave and demands careful and politically attentive storytelling.

At first glance, the film appears aligned with this responsibility. However, despite its seriousness, the film gradually loses hold of its own argument. In doing so, it weakens a feminist imagination that repeatedly collapses justice into rescue, empowerment into individual heroism, and structural violence into a problem that can be solved by authority alone.

Borrowing masculinity: the politics of the title

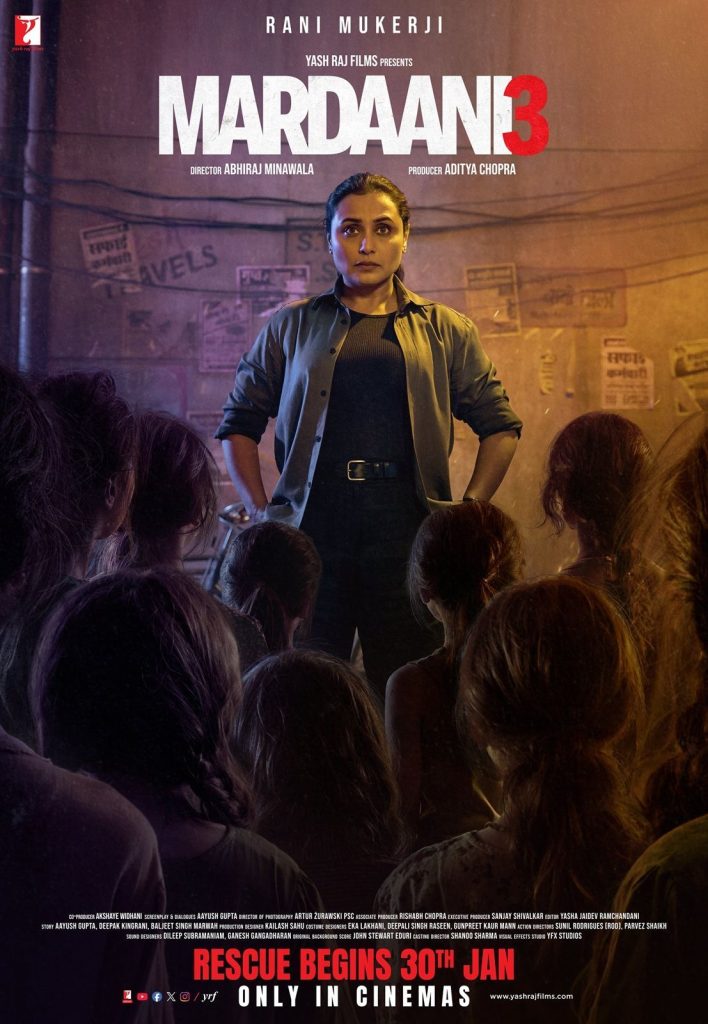

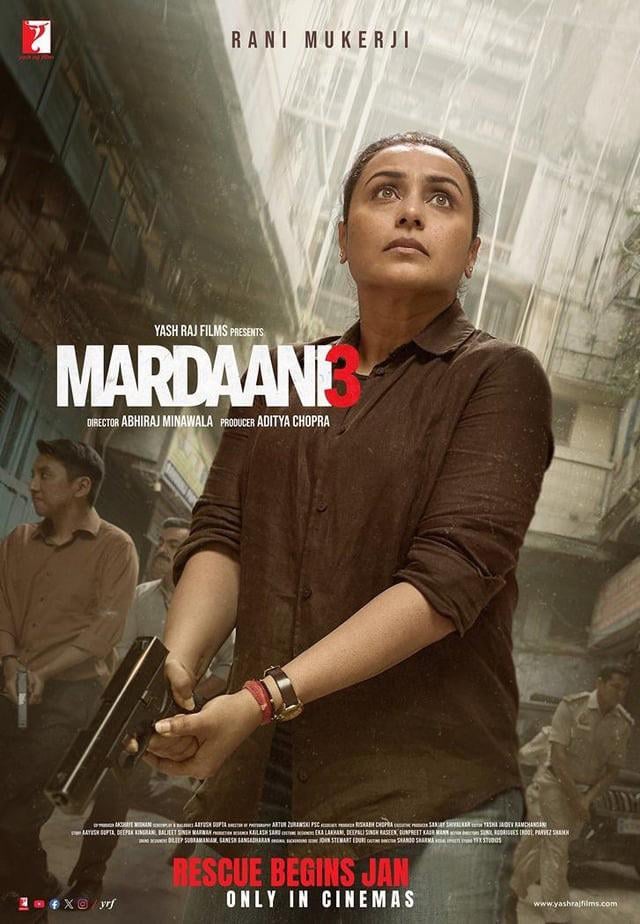

The third instalment of the Mardaani franchise, Mardaani 3, released on 30 January, is directed by Abhiraj Minawala and produced by Aditya Chopra under the banner of Yash Raj Films. Rani Mukerji reprises her role as the formidable police officer Shivani Shivaji Roy, alongside Janki Bodiwala and Mallika Prasad. By now, the franchise carries with it a set of expectations, of issue-based cinema, moral clarity, and feminist resolve; expectations that this film inherits but struggles to meaningfully extend.

Even before the narrative unfolds, the franchise’s long-standing title invites scrutiny. Mardaani literally translates to “manly,” a term historically deployed to signify courage, aggression, and authority. That a film series positioned as feminist continues to frame strength through a masculine idiom is not incidental.

It echoes a familiar cultural refrain within Indian households, where daughters are praised by being told they are “not daughters, but sons”, as in ‘aap to humare bete ho.‘ Compliments such as these, with seemingly progressive, ultimately reinforce the idea that power becomes legitimate only when it mirrors masculinity.

Strength becomes legible only when it borrows masculine codes of authority; the female cop is validated precisely because she performs power in ways indistinguishable from her male counterparts: omniscient, infallible, almost God-like.

This framing runs as an undercurrent throughout the film. Strength becomes legible only when it borrows masculine codes of authority; the female cop is validated precisely because she performs power in ways indistinguishable from her male counterparts: omniscient, infallible, almost God-like. In replicating this model, Mardaani 3 does not so much challenge patriarchal notions of power as inherit them wholesale.

Trafficking, class, and the politics of invisibility

The central thread sewing the entire narrative is that of trafficking and invisibility. With its focus on pre-pubescent girls, the film grows increasingly graphic, both thematically and visually. The victims are largely drawn from poor communities in Delhi, foregrounding invisibility as a social condition produced by the double disadvantage of gender and class, often compounded by caste.

Until power intervenes, representation steps in only sporadically; cases like the disappearance of dozens of girls remain absent from mainstream concern, even though such narratives are far from distant from on-ground realities.

Formula over depth: writing, dialogue, and direction

However, no matter how serious the theme, if the narrative structure remains loose, the impact falters. Mardaani 3 feels deeply formulaic in its storytelling. Its procedural structure is predictable, following a familiar cop-versus-criminal arc that leaves little room for surprise or sustained tension.

Borrowing from the Singham-style god-saviour cop template, the film mainly changes the gender of the protagonist without reworking the imagination of power; the film highlights how superficial representation can substitute for meaningful rethinking. Narrative convenience repeatedly overrides emotional and ethical depth, weakening what could have been a far more unsettling engagement with violence.

The dialogue, in particular, contributes significantly to its dilution. Lazy writing seeps through the script with meme-inflected, casually tossed lines such as ‘fielding set karni padegi,’ deployed even in moments of trauma. While this register may appeal to contemporary audiences, it flattens emotional complexity and trivialises suffering in the name of accessibility. Serious violence spoken in disposable language becomes easier to consume and easier to forget.

Serious violence spoken in disposable language becomes easier to consume and easier to forget,

Performance-wise, the acting remains largely sharp. Rani Mukherji brings a controlled intensity to Shivani, while Mallika Prasad’s portrayal of Amma carries a quiet menace. The supporting cast performs competently. Yet even strong performances struggle to transcend loose writing.

The film constructs a stark moral binary wherein the good side is embodied by Shivani and the evil side is personified by Amma, reaffirming its discomfort with systemic interrogation. Violence becomes an individual failing rather than a systemic and structural condition.

Spectacle without interrogation

Shock is frequently used to escalate stakes. Gruesome visuals, whether of carrying a dead child in a polybag or acts of brutal physical harm, are undeniably striking and leave the viewer gasping.

The visual treatment, supported by effective cinematography, set design and direction, succeeds in unsettling the audience. Yet, this shock rarely translates into deeper moral inquiry. Spectacle substitute reflection.

Beyond visuals, the film is riddled with narrative loopholes and logical inconsistencies, making the suspension of disbelief increasingly difficult to sustain.

While both sides (the cops and the villains) are afforded backstories, motives and emotional shading, the central subjects of the story remain sidelined. The children themselves are denied interiority. Their fear, confusion, and endurance remain largely unexplored.

When addressing an issue as grave as child trafficking, victims cannot remain mere narrative stakes awaiting rescue by a saviour figure.

This absence is perhaps the film’s most glaring limitation. When addressing an issue as grave as child trafficking, victims cannot remain mere narrative stakes awaiting rescue by a saviour figure. By refusing to centre the children’s perspectives, the film inadvertently generates greater empathy for authority figures, even for villains, than for those who suffer the violence. The authority-centred empathy weakens the film’s feminist claim.

Beyond the “strong female cop”: what feminist cinema still owes to us

Despite its limitations, Mardaani 3 is not without significance. In a society where the disappearance of girls is often normalised, even ignored, the act of naming the violence matters. Mainstream cinema reaches audiences that academic discourse and policy debates often do not, confirming conversations in spaces otherwise resistant to them.

However, the figure of the “strong female cop,” as seen not only here but across recent crime dramas, such as Delhi Crime, cannot be treated as a feminist endpoint. Strength framed solely as individual resilience obscures the collective failures that make such heroism necessary in the first place.

Mardaani 3 offers resolution through rescue and closure through punishment, but stops short of interrogating the conditions that allow girls to disappear so easily to begin with.

In the end, Mardaani 3 is a competent, occasionally unsettling, but ultimately cautious film. For a franchise that has built its identity on confronting violence against women, this caution feels like a limitation worth naming. Justice, after all, is not only about finding the missing; it is more about asking why they were allowed to disappear in the first place.

About the author(s)

Ananya Shukla is a development communication researcher and poet currently pursuing her Master's at Jamia Millia Islamia. Her work bridges academia and creative expression, using media like documentaries and poetry to explore how storytelling can drive social change.

Insightful and well worded. You possess the panache and poignancy of a seasoned critic. Blessings and best wishes.

There’s no greater reward for a writer than knowing their thoughts found a meaningful connection. Thanks a bunch Yusuf!