The world of literature has always been a place where social status is captured, defended, and, in some cases, criticised. Not every life has been equally represented in the history of literature. Intersectional writing is an acknowledgement of the overlapping of identities, i.e. caste, gender, class, religion, and ability, among others, and it plays an important role in the explanation of oppression, which cannot be explained by only one factor. To Dalit women, opposing is never merely a question of caste or gender, but a relationship of both simultaneously.

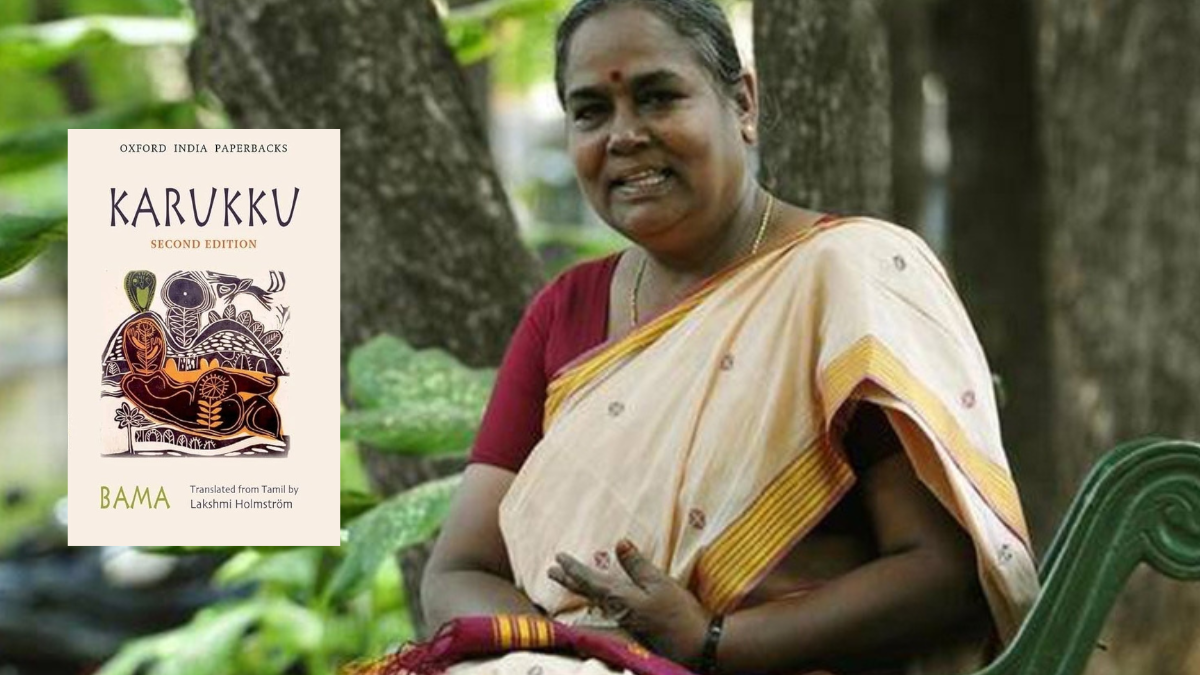

Bama, Baby Kamble, Urmila Pawar, Shantabai Kamble, and other writers have been instrumental in bringing the realities of Dalit women into literature. Their works defy not only upper-caste literary cultures but mainstream feminism, which does not necessarily consider caste. Of these, the Karukku by Bama (1992) is one of the first Dalit feminist writings to reveal how caste and gender, in collaboration, create a form of marginalisation that is both kind and severe. Karukku demonstrates that survival itself can be a political act through memory, anger, humour, and resistance.

Understanding double marginalisation

Karukku is often described as an autobiography, but it is more accurately a collective life narrative. Bama does not only write about herself, but she writes about a whole Dalit community, particularly Dalit women, whose lives are determined by humiliation on the basis of caste, and control of the males. Since she was a child, Bama has come to realise that being a Dalit means she is inferior to the rest of society. She remembers that Dalit people were supposed to be subdued before the landlords of the upper caste, even in the minutest of things. Among the most quoted passages in Karukku is her account of watching an older man, a food carrier for an upper-caste man, pick up the food without touching it, an event that makes her understand the extent to which caste humiliation is rooted in ordinary lives.

For Dalit women, this humiliation is intensified by gender. As Bama demonstrates, Dalit women are exploited by dominant castes, as well as by other people of their own caste. Whereas the Dalit men are victims of caste violence in civil places, the Dalit women are victims of caste violence in both civil and domestic places, in hard labour, domestic violence, and social control. Their bodies are as open as they are, and their labour is assumed. Bama points out that Dalit women are the most unappreciated, underpaid, and overworked. It is this kind of doubled marginalisation that makes intersectional narratives significant. The analysis of caste cannot be complete without gender, and vice versa, because caste narratives are male-dominated without gender. According to Karukku, the experience of the Dalit woman cannot be secondary or auxiliary; it should be central.

Collective laughter and solidarity as everyday resistance

The ability of Karukku to focus on collective laughter and community engagement is one of its strongest features, which is rarely acknowledged. Even in a situation like extreme poverty, violence, and humiliation, Dalit women in Bama’s autobiography laugh, tease each other, exchange stories, and create emotional support systems with each other. This is not a mere laughter, but a laughter which is political. Bama narrates instances of women who have worked hard throughout the day, sitting down together, laughing and telling jokes, moments that act as catharsis for their suffering and as a way to restore humanity in a world that has not given it to them. The laughter can be seen as a subversive form of protest against the caste society that expects them to remain silent, ashamed, and broken.

In contrast to dominant narratives, which largely focus on Dalit communities in the context of suffering, Karukku shows that community relationships enable women to survive and that solidarity serves as a tool of resistance. By centring these everyday acts, Bama expands the idea of resistance beyond protests or revolutions, and shows that survival, joy, and togetherness are themselves political in contexts of extreme oppression.

Refusal to internalise shame

Caste is not only present as a result of physical repression, but also as a result of psychological violence, which stems especially as a result of shame. The Dalit groups have been constantly instructed for centuries that they are filthy, lesser, and undeserving. Among the most radical actions of Karukku is Bama’s refusal of this shame.

Being a child, Bama does not experience shame at first when she gets to experience caste discrimination. Instead, she feels confused and angered by it. As she grows older, she begins to reject the notion that shame is attached to being a Dalit. Even when they are considered as “uncivilised” by the dominant society, Bama writes proudly about the Dalit culture, language, food habits, ways of living and the simple pleasures in a very native way.

Bama too rejects the moral discipline that is practised on the Dalit women, particularly in the form of religion. The experiences of Bama as a Dalit Christian woman can help us understand her early life experiences of the way the Church teaches equality, but plays out caste discrimination and patriarchal subjection. When she discovers that the Church is using Dalit labour and at the same time expects her to obey and be silent, she decides to quit engaging with the institution. It is a sign of her denying systems that require only the oppressed to be humble and make sacrifices.

Bama reclaims her body, voice and identity by denying shame. Such rejection is noteworthy because internalised shame is one of the strongest caste tools of oppression. Karukku shows that dignity begins by rejecting the falsehoods people try to impose about others.

Writing as survival and political testimony

Perhaps the most important act of resistance in Karukku is writing itself. Bama writing is not a literary practice, but a method of surviving, healing, and witnessing. She has said that Karukku writing was like opening the door and cutting herself open, which may be painful, but needs to be done. The title Karukku, or sharp-edged palmyra leaf in Tamizh, symbolises both suffering and strength.

The Karukku language is direct and unapologetic. Bama does not play down her words to meet the tastes of the elite literary demands. In such a way, she questions the concept of what constitutes good literature. Her everyday speech and oral narrative traditions make the voices of Dalit women heard in a space where they had none before. It is also through writing that one seeks to ensure the experiences of Dalit women are not lost. In her narration, Bama tells the story of many others who did not have a voice and were not given a chance. Karukku claims that the lives of Dalit women are not irrelevant and that they need to be heard in their own voices.

Karukku is a seminal work of Indian literature, demonstrating how a combination of caste, gender, and other factors shapes lives marked by struggle and resistance. Bama provides the Dalit feminist perspective to the world in a strong way through laughter, solidarity, and refusal of shame, through writing as survival, and by showing that intersectional narratives are key to the true picture of oppression.

About the author(s)

Dharanesh Ramesh is a native of Coimbatore and a postgraduate student of Gender and Development Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad. Rooted in the belief that stories shape structures, his study and work explore the intersections of gender, caste, and public policy through an intersectional feminist lens. He is particularly drawn to understanding how power, privilege, and policy weave together to define inclusion and equity in everyday life. Inquisitive by nature, Dharanesh often turns to drawing, painting, photography, and writing as extensions of his reflective practice. His work seeks to bridge thought and experience, analysis and art, in the pursuit of justice and representation.

Comments:

Comments are closed.