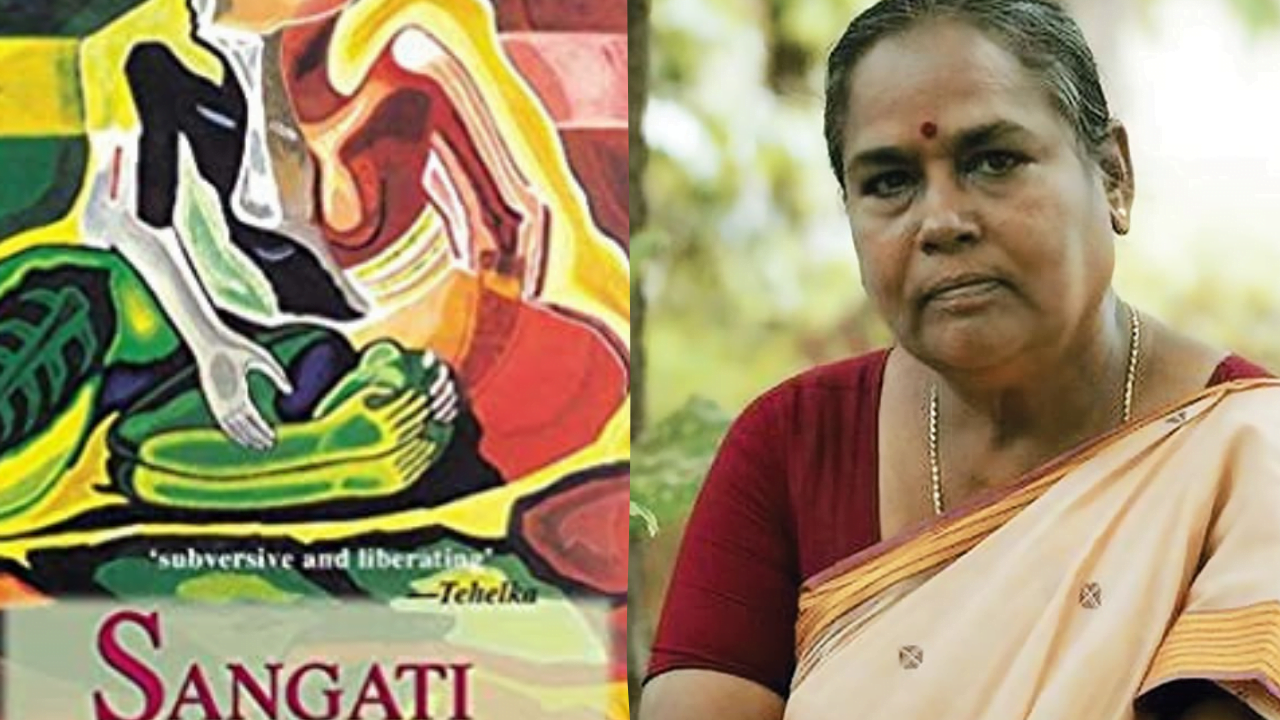

Sangati is a collection of life narratives of Dalit women’s experiences told by a young Dalit woman, Bama, looking into her past. It is a sequel to Bama’s first novel Karruku, an autobiographical novel written in 1992 (first translated into English in 1999). Understanding experiences necessitates engaging with analysis of the intersecting, multiple identities that we hold. Sangati, does this in insightful and moving ways, through narrating the stories of a Dalit women community from this intersecting lens. This book offers us insights into the lives of Dalit women from the different generations for whom resistance, fight, hope, love, and anger are part of their daily negotiations. This book also offers fresh understanding into caste-based patriarchal society from Dalit women’s’ perspectives, which unravels new considerations for Dalit women’s’ identity and agency.

The struggles associated with society’s imposition of norms of behavior and treatment because of one’s identity creates a powerful impact on the people situated at the bottom of the ladder. Bama’s narratives show how Dalit women fit into this caste-based patriarchal society where even minimal, fundamental rights such as eating, free mobility, physical security becomes a hard negotiation in daily lives. She describes all aspects of women from Paraiyar community, a Dalit Tamilian caste, from unhappy married life, public humiliation, private humiliation, harassment, subjugation, …and yet how they are still able to lead their life happily. By narrating the stories of Dalit women, Bama wants to share the “rebellious celebration” as a response to the hardships of the Dalit women in her story. She writes-

My mind is crowded with many anecdotes: stories not only about the sorrows and tears of Paraiyar women, but also about their lively and rebellious culture, their eagerness not to let life crush or shatter them, but to swim vigorously against the tide; about the self-confidence and self-respect that enables them to leap over threatening adversities by laughing and ridiculing them; about their passion to live life with vitality, truth, and enjoyment, about their hard labour. I wanted to shout out these stories. I was eager that through them, everyone should know about us and our lives.

BAMA, 2005, IX

Along with the hardships, Bama talks about the cultural identity of Dalit women which strongly resists patriarchal and caste-based norms which historically exist to suppress them. Bama narrates several incidents, touching upon many unheard and unseen events, where oppressive structure tried to suppress Dalit women within as well as outside the households. Bama says that Dalit women are not only oppressed by the men in their community but also by the members of the upper castes’ community. Referring to abusive marriage in chapter 9, she probes some valid social questions like “But why must she (Dalit women) do what they (society) ask? Why can’t she ignore what they (society) say, and stay where she chooses?” (p 96). These questions not only challenge the patriarchal structure, but they also echo the resistance by Dalit women by asking ‘why’ of the situation. The underline message Bama wants to convey is for Dalit women to ‘be aware of our situation’ and its importance to challenge this subservient position by believing in our independence (p 59).

From birth, women are considered less valuable in a patriarchal society like India. Cultural norms favour boys/male members of the family. Even in minor privileges like eating food, boys are given priority over girls/women of the house. Bama raises the issue of gender discrimination by writing; “If a boy baby cries, he is instantly picked up and given milk. It is not so with the girl. Even with breastfeeding, it is the same story; a boy is breastfed longer, with the girl, they bear them quietly, making them forget the breast” (p 7).

Also read: ‘Karukku’: An Autobiography By Bama Exploring Her Tamil, Dalit And Christian Identity

Bama challenges such a cultural inclination towards gender in this book. She also raises some impudent questions like, “Why can’t we be the same as boys? We aren’t allowed to talk loudly, we always have to walk with our heads bowed down, gazing at our toes…even when our stomachs are screaming with hunger, we mustn’t eat first. We are allowed to eat only after the men in the family have finished and gone. What, Patti, aren’t we also human beings?” (p 29) Indeed, the right word, human-being! This word erases the privileges or marginalisation comes with the identity when identifies as one gender. Using ‘human being’ is symbolic here to look beyond the identity associated with one gender or privileged caste.

Bama portrays real pictures of Dalit Paraiyar women, bringing to light moments which lie in the daily negotiations of their identity in comparison to non-Dalit women. For example, in comparing the realities between upper-caste women and the women of her community she writes, “It is not the same for women of other castes and communities. Our women cannot bear the torment of upper caste masters in the field, and at home, they cannot bear the violence of their husbands” (p 65). Bama also shares moments from her childhood, as she gets lessons at thirteen years old on how to navigate those plain fields to save herself from upper-caste men. It is a striking reality that should shake our souls and our consciousness, “They (upper caste men) will drag you off and rape you, that’s for sure” (p 8). She was taught to be careful, and how to navigate those land which are not for us (Dalit women). How just is this society if a thirteen-year-old had to learn a lesson to protect herself from caste and gender-based atrocities? Are we still asking our daughters to be careful because some people simply have not evolved as humans?

Also read: Book Review: Vanmam – Vendetta By Bama

In brief, this book is for those who want to understand the Dalit women experiences from their own narrative. It challenges the deficit models used in the current dominant discourses on Dalit women by bringing the story of resistance and rebel. These discourses will be significantly informed by the experiential dimension of the compounded nature of caste and gender theories from Dalit women’s perspectives, particularly in India. It unravels some hidden territories of Dalit women’s lives which bring an experiential dimension to the existing literature—which is dominated by men—often intellectualizes and thereby “masks rather than explains the structure” of the caste system in India.

References

- Chakravarti, U. (2018). Gendering caste: Through a feminist lens.

- Fuchs, S. (1990). Asian Folklore Studies, 49(1), 174-176. doi:10.2307/1177971

- Sangati, translated copy from Tamil to English by Lakshmi Holmström

Shikha Diwakar is a doctoral student in the Department of Integrated Studies in Education at McGill University. Her research area focuses on understanding the role and impact of Dalit women’s identities on their life experiences. You can find her on Linkedln.