A lot of us are all hot and worked up, not only because it is summer but also because of India’s ongoing Assembly elections. During the campaigning of political parties, accusations of possible privatisation of public services, increasing tax of certain amenities did not only make their rounds but also moved the citizens/voters to think of the implications of such policy changes in their lives. An eminent missing piece from the larger narrative around economic equity and agency is how national economic policies and international financial institutions contribute to gender inequality. Certainly, we can’t move past this without questioning, thinking, transforming.

An eminent missing piece from the larger narrative around economic equity and agency is how national economic policies and international financial institutions contribute to gender inequality. Certainly, we can’t move past this without questioning, thinking, transforming.

Engaging with international institutions, national economic policies, looking at them critically, and building a gender-responsive structure can often be perplexing. Feminist organisations working at the local level are promising in their potential of mobilising women affected by such economic policies, owing to the fact that they are often working with women’s groups, communities, and marginalised people in issues of social justice and equity.

‘Economic policies’ are the decisions and plans that governments make related to the distribution and provision of goods, services, and money. Economic policies include, for example, how much tax to charge and who should pay it, what public services to provide, how many nurses and teachers to hire, and how to support people unable to find work, people who are too old to work, or women who are pregnant – known as social protection.

Also read: What Are The Ways In Which Global Economic Policies Affect Local Gender Issues

International financial institutions are supposed to maintain global economic harmony by providing loans to countries, financially helping them in crisis, and thus positioning themselves in a place of power where they can offer financial advice and recommendations for a country’s economic growth. The reports by such international financial institutions are very influential, that most governments, especially in poorer countries, follow their recommendations. How a country’s government chooses to respond to them can deeply and disproportionately affect the citizens of the country.

The economic policies affect men and women differently as we live in a deeply hetero-patriarchal system where expectations around the roles that men and women should play in society mean different. Women undertake a disproportionate amount of unpaid care and domestic work, including looking after children, the sick, and the elderly, fetching water and food, and preparing meals. Men are seen as responsible for paid work outside the home. When women do paid work it is often in the informal economy, where worker’s rights are not protected and jobs are low paid and insecure.

Often the recommendation by international financial institutions includes cutting off public services or privatisation of goods or increasing the tax. When Ghana borrowed money from the IMF in 2005, the IMF told the government to cut the country’s public sector wage bill (the amount of money the government spends on public sector salaries) by about USD$93 million (a 6% decrease). The government argued against this, claiming that the health service was losing highly trained staff, making it difficult for the government to reach its health service goals. Although the IMF eventually removed this conditionality, before they did so, the government refused to honour the wage agreement it had agreed with registered nurses. The number of doctors working in the public sector halved, and the number of nurses and midwives fell by 26% between 2004 and 2007. Although Ghana’s maternal mortality rate did decrease over this time, Ghana did not reach its 2015 Millennium Development Goal target. This was mostly because of limited availability of specially trained nurses and midwives in rural areas.

If the government of the country includes such recommendations in their economic policies, the burden is primarily implicated on the lives of women. For instance, child-rearing is primarily seen as the responsibility of women. Now the privatisation of child care centers or not providing child care centers as a free public service takes away the possibility for women to work. Also, the amount of money one might have to pay in a child care system might be higher than their salary. This clearly deprives women of their economic independence and participation.

We are now in the middle of a global humanitarian crisis with the Covid-19 pandemic adversely affecting not just economies but also the public healthcare systems of countries. The pandemic did not just pull girls out of schools, it also heightened financial vulnerabilities and raised their care-giving responsibilities.

Also read: What Is The Link Between Economic Policies And Women’s Rights?

The discrimination is more on women whose identities are further marginalised because of their age, sexuality, caste, class, etc. The more the marginalisation, the more it becomes difficult to find spaces that affirm the experiences of marginalised women, make them understand whom to hold accountable, and how to put a structure in place for advocacy.

Unfortunately, the labour and onus of demanding accountability fall on the marginalised women who are worst hit by such policies. Feminist organizations working at local level can initiate the conversation with communities primarily through mobilising them and helping them identify the problem.

Why international financial institutions need to be held accountable?

International financial institutions and national governments are responsible for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the human rights of citizens, including young women and marginalised people. Though they might appear cognizant of that responsibility, in practice, there are many reasons why governments can’t or won’t keep those promises. For many countries, especially countries that are very poor or have high levels of debt, one major reason is the power and influence of the International Financial Organizations and their policies which protect and promote the interests of international capital.

The push for privatisation of public services made by these inter-governmental/multilateral bodies to favour the interests of powerful corporations have led to multiple negative impacts on local-level, gender-responsive public service (GRPS) provisions for women and girls such as access to affordable food and household items, paid work, water, and sanitation, childcare, healthcare, and education.

Role of feminist organisations in holding international financial institutions accountable

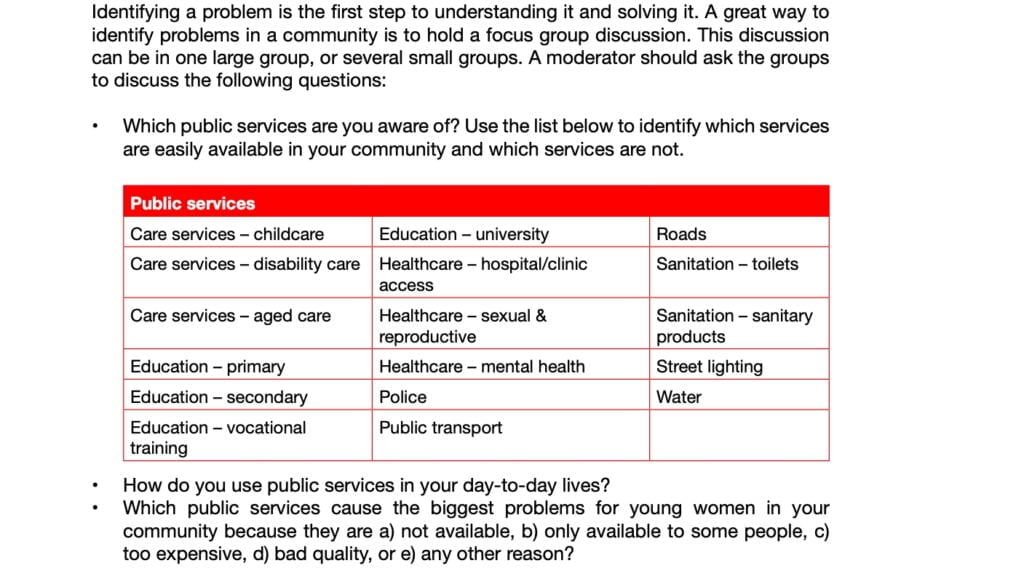

Identifying the specific problem: The problem might appear too broad or difficult to intervene, so zeroing down to specific problems created by economic policies, in specific communities is pivotal. This is also owing to the fact that marginalisation of women and how they are impacted depends/changes with their socio-geo-economic positioning. Here is where feminist organisations can help women to come together and be part of processes of streamlining and consolidating collective concerns.

Feminist organisations working at local level can facilitate focus group discussions with local women and other marginalised groups. The discussion may include key points around, which public services are they aware of? how do they use public services in their day-to-day lives? which public services cause the biggest problems for young women in their community because they are a) not available, b) only available to some people, c) too expensive, d) bad quality or e) any other reason, etc.

Once the group zeroes down to one or a couple of specific problems that are prevalent in the community and deserve immediate intervention, a social audit can be done to further build a case.

Investigating the actors in the act: The purpose of a social audit is to consider the quantity, quality, affordability, and accessibility of services that are needed for women to enjoy their rights. Doing a social audit can help identify where services are lacking, too expensive, or poor quality.

A social audit should consider the following questions:

Quantity: Are there enough services (provided by the government) for the community?

Quality: Does the service need improvement (for example, is it functional, how far is it safe to use, is it appropriate, does it meet young women’s needs?)

Affordability: How much do they cost? Who can afford to access them?

Access: Who is able to access these services? Are they located in a convenient location? Are they open at convenient hours? Who is left out?

There are a number of guides and videos online that can help one learn about how to do social audits. Detailed information can be accessed here: www.socialaudits.org.za or feminist organisations can reach out to organisations/persons with relevant expertise.

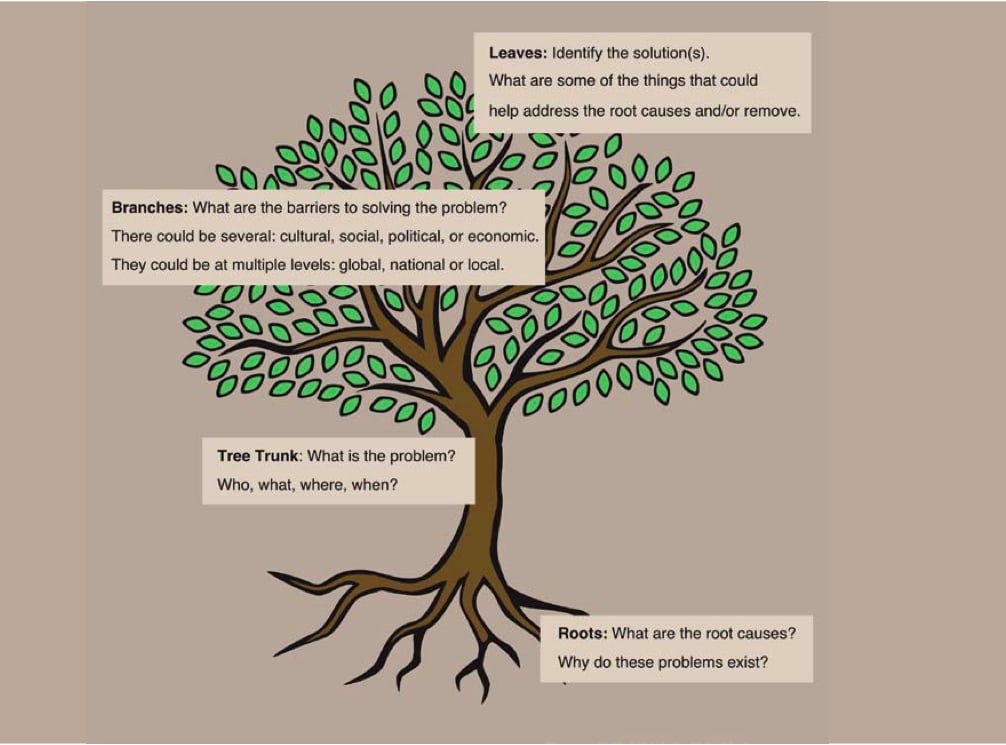

With these primary fact-finding, evidence generation, and scoping, the group can then consolidate and analyse all the gathered information through analytical tools. For example, mind mapping or problem tree analysis.

Analysing the problem, solution, and challenges: Identifying the causes of a problem is key to understanding which solutions will be most appropriate. The Problem Tree activity is a great way to identify root causes, solutions, and possible barriers to those solutions. It is helpful to identify barriers in advance so they can be avoided or so that follow-up activities can be designed to overcome them.

The root causes may be social norms or national or local politics. The root causes may also be linked to economic policies, including policy advice and loan conditionalities issued by an international organisation.

Branches can indicate what are the barriers to solving the problem? The response could be several: cultural, social, political, or economic. They could be at multiple levels: global, national, or local. And ultimately the leaves can indicate possible solutions.

With all this gathered information the feminist organisations working at a local level, along with the community can brainstorm about setting up realistic goals that hold iternational financial institutions and local government accountable.

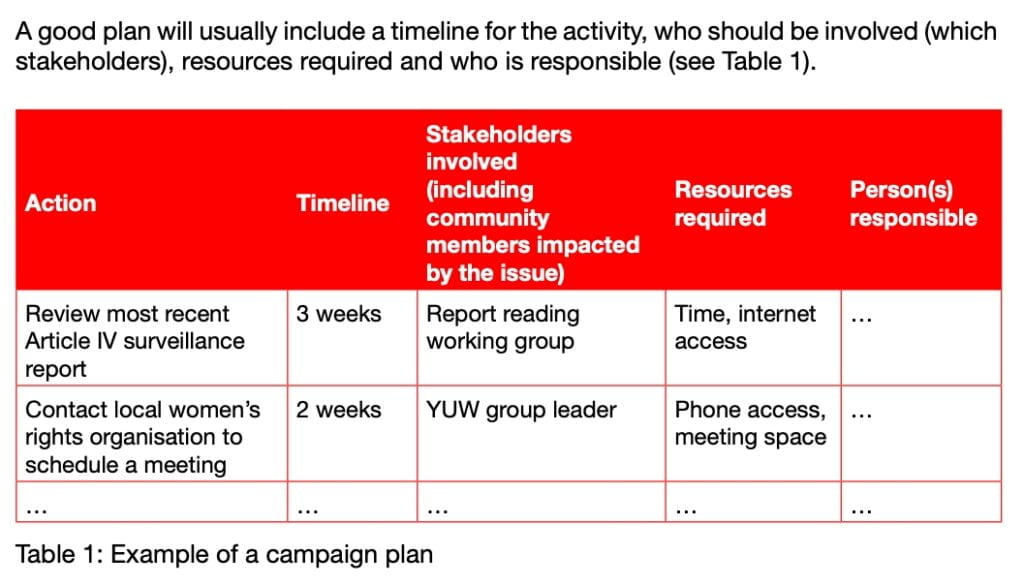

Setting realistic goals: Goals can be very simple or very complex, depending on the problem at hand. For example, a goal can be to improve access to clean water for women in a certain community which in turn is likely to depend on the budget that the local government of that community has to make that change happen. This, in turn, will be influenced by the overall budget for the whole country, which might be affected by commitments made by the national government to the big financial institutions when taking out a loan. A good plan to reach the goal will include a range of activities that use real stories and evidence (such as information gathered through social audits) to highlight injustice and policies that need to change. Campaigns should have a specific ‘ask’ – what is the problem and what solution should be implemented by policymakers?

When deciding which issue to focus on, the group needs to prioritise the issues that can change realistically and will have the strongest level of support from other young women, the wider community.

Once a goal has been defined, it is important to develop a plan that includes a list of activities needed to achieve that goal. The plan can include a whole range of activities, including more research, campaigning, community workshops, collective action, and meetings with government representatives.

Governments are ultimately responsible for listening to citizens and ensuring their human rights are protected. International financial institutions only provide policy advice, which countries can choose not to follow. And although it can be challenging for a country in debt crisis, loan conditionalities can be negotiated. In the bigger picture, international financial institutions have to be mindful of their recommendations on how they might perpetuate gender inequality.

Governments are ultimately responsible for listening to citizens and ensuring their human rights are protected. International financial institutions only provide policy advice, which countries can choose

Though the spaces created by internatiFIs that promises gender equality has been critised for its fallacies, those are also the links where feminist organisations can engage to advocate for equity. For example, ‘Operational Policy 4.20 on Gender and Development’ by the World Bank aims to help member countries address gender inequalities in World Bank investment projects. Alongside this, their latest Gender Strategy, updated in 2016 following consultations with more than 1,000 stakeholders in 22 countries, applies to all group entities, including the private sector arm IFC.

International Monetary Fund’s interdepartmental Fund’s Gender Advisory Group was created in 2015, to provide analytical and operational support to pilot country teams, build and share knowledge and expertise on gender issues, and facilitate external collaboration. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has an Economic Inclusion Strategy, focusing on participation in the economy for groups who could be disadvantaged and a “Strategy for the promotion of Gender equality”. The European Investment Bank Gender Strategy focuses on the “Protect’ route (taking gender into account in the due diligence of EIB operations), the “Impact” route (embedding a gender perspective throughout an investment cycle, identifying opportunities within operations and disseminating best practice) and an “Invest” route (Identifying targeted opportunities to invest in women’s economic empowerment).

Engaging through such spaces and holding such big institutions accountable might seem overwhelming or unachievable and that is why collective action is at the core of the solution. Building solidarity and networking among women’s rights and feminist organizations, worker organisations, trade unions, community leaders, religious leaders, and international human rights organisations, organizations/people with shared interest and experience not only accelerates the process but also adds value to the movement.

Featured image source: Shreya Tingal/Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Sudipta Das(He/They) is a communications professional having experience of working on issues around gender-based violence, child rights, queer rights and sexuality. They have been an India Fellow'17 and a Likho Citizen Journalism Fellow'19. They believe in intersectional feminism and wish to write elaborately on the subjects of media, caste, sexuality and mental health.