This piece has been written in light of Frida Kahlo’s forthcoming birth anniversary, on the 6th of July. It is a review of her diary, published as The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self Portrait, and translated from the Spanish by Barbara Crow De Toledo and Ricardo Pohlenz.

The Diary of Frida Kahlo illustrates the last ten years of the life of the renowned Mexican painter from 1944 to her death in 1954. It is a rare glimpse into one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century, illustrated not just by colour but also by the lyric

The Diary of Frida Kahlo illustrates the last ten years of the life of the renowned Mexican painter from 1944 to her death in 1954. It is a rare glimpse into one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century, illustrated not just by colour but also by the lyric. The journal has seventy water colour illustrations which are accompanied by several text entries in color inks. It has been scanned and presented in the book in its original form, with ink blots and strike outs, accompanied by a complete translation of the diary entries in the last thirty pages.

Also read: Frida Kahlo – The Woman, The Artist, The Feminist

With gutting clarity, Frida Kahlo writes—

There is nothing more precious than laughterand scorn – it is strength to laugh

and lose oneself. to be cruel and

light.

Tragedy is the most

ridiculous thing “man” has

but I’m sure that

animals suffer,

and yet they do not exhibit their “pain”

in “theatres” neither open nor

“closed” (their “homes”).

and their pain is more real

than any image

that any man can

“perform” xxxx or feel

as painful. __________

Throughout the diary, Kahlo frequently meditates on the nature of pain. Kahlo suffered through many accidents that left her in frequent physical distress. At the age of five, she was diagnosed with Polio. She recovered, although her right leg continued to show the damage inflicted by the disease. But a greater affliction was yet to come. At the age of eighteen, Kahlo was travelling in a wooden bus with her boyfriend, when a streetcar crashed into it. Kahlo suffered immense damage to her spinal column, collarbone, her ribs and her pelvis. Her formerly polio affected leg suffered eleven fractures. In the coming years, Kahlo had to endure more than 35 operations to recover from the accident she had at 18.

Her right leg, a cause of major suffering, returns to her drawings again and again. In a jarring image, Frida Kahlo paints a headless woman with a shattered spine. A spiral line encircles the left leg. Wings sprout from where the two arms of the woman should have been.

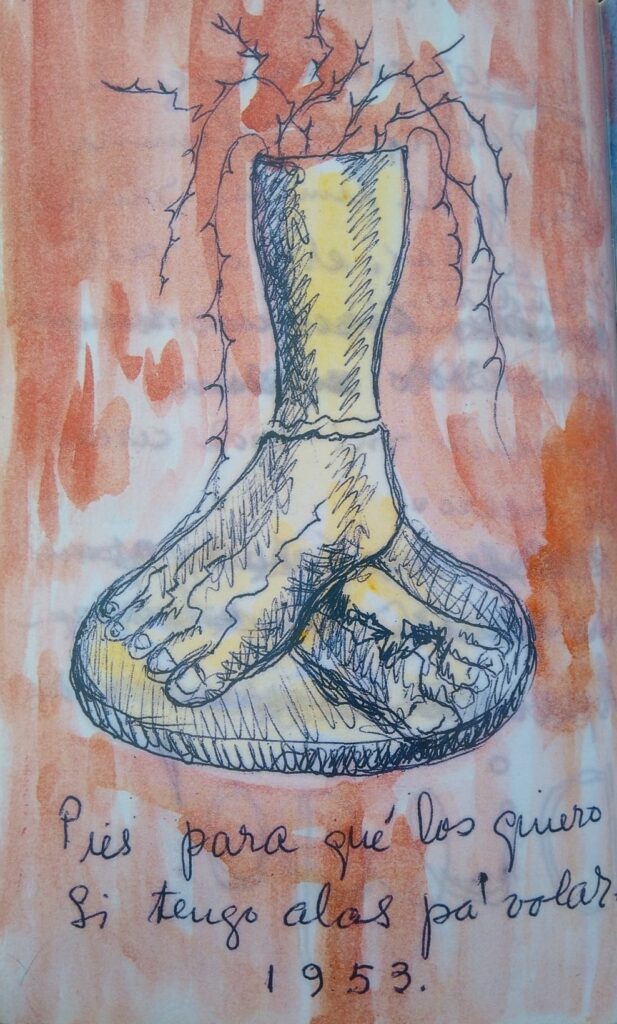

In another image, Kahlo paints two disembodied feet held upon a dais, and thorny vines emerge from them. The accompanying line at the bottom of the drawing is a quote that has now become famous, and is often cited in relation to Kahlo’s inspirational spirit–“Feet what do I need them for if I have wings to fly”. In another entry from the same year, she echoes the sentiment again—“ I have many, wings. Cut them off and to hell with it!!”.

Both of these drawings are dated 1953. This was the when the gangrene in her leg had spread, and the amputation of her right leg appeared inevitable. In an accompanying entry, Kahlo writes:

August 1953.

It is certain that they are going

to amputate my right

leg. Details I don’t know very much

but the opinions are very

reliable. Dr Luis Mendes

and Dr. Juan Farill.

I’m very very, worried,

but at the same time I feel

it would be a relief.

In the hope that when

I walk again

I’ll give what remains of

my courage

to Diego.

everything for Diego.

Deigo Rivera was a famed Mexican painter, and Frida Kahlo’s love interest. He had first met Kahlo when she was still a school girl. She showed Rivera her paintings, and he was very appreciative of Kahlo’s work. They had a tumultuous relationship– they married, they divorced, and they married again. However, Diego keeps appearing in the journal, an interest incomparable to any of the others of Kahlo’s probable lovers. A passage dated 1938, which was written while she was in New York and in an affair with another man, mentions Diego in the following words—“Name of Diego—Name of love. Diego is the name of love”. Diego, irrespective of the turmoil, is a constant meditation. She calls him “my Diego”, “my child”, “my newborn babe”.

Also read: Watch: The Life And Times Of Amrita Sher-Gil

Kahlo was a passionate communist. She names Marx, Stalin and Mao– constantly affirming her revolutionary spirit, and her incessant wish to be “always revolutionary, never dead, never useless”. In a severely touching moment, she laments not being able to be of use to the party. She relates her art and revolution, and talks of her uneasiness:

I feel un-

easy about my painting. Above

all I want to transform

it into something

useful for the Communist

revolutionary movement

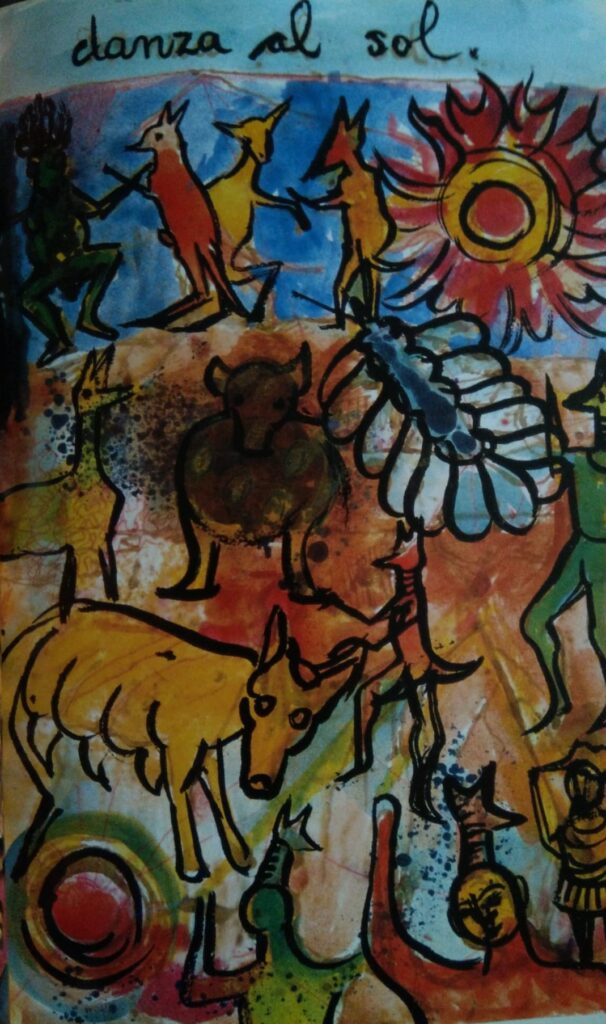

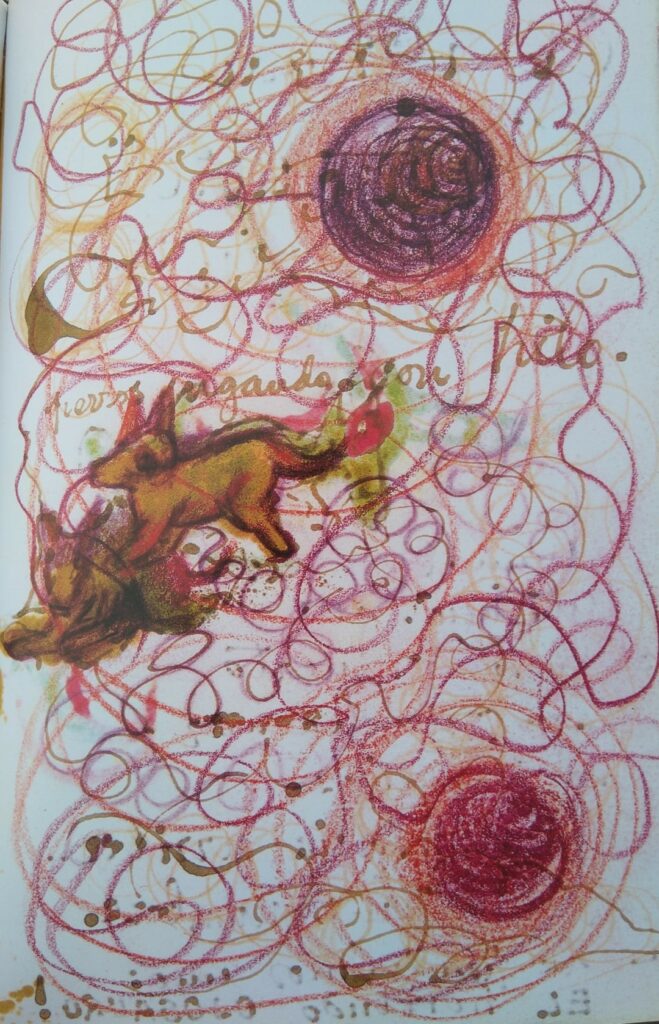

The diary is populated with nude women, often placed in surrealist encounters. In ‘The Phenomenon Unseen’, three nude women stand with many limbs and many heads. Genitalia, eyes and ears crop up in unexpected places. Her joy too is never far. In a picture titled ‘Dance to the Sun’, real and mythical animals dance, the page rejoicing in bright yellows and reds. In another, titled ‘Dogs Playing with Thread’, colour lines run across the page, twisted and entangled. And in the midst of them, two dogs play.

Her joy too is never far. In a picture titled ‘Dance to the Sun’, real and mythical animals dance, the page rejoicing in bright yellows and reds. In another, titled ‘Dogs Playing with Thread’, colour lines run across the page, twisted and entangled. And in the midst of them, two dogs play.

The diary is also marked by her persistent love for those around her. In an entry from 1954, from a time when she was relatively well and recovering, she writes:

Thanks to myself and

to my powerful will

to live among those

who love me and for

all those I love.

In the last written entry from the diary, as Frida Kahlo waits in the hospital, she thanks her doctors and nurses, and writes,

I hope the

leaving is joyful – and I hope

never to return –

FRIDA

References

Kahlo, Frida, et al. The Diary of Frida Kahlo: an Intimate Self-Portrait. Abrams, 2005.

Vinky Mittal is an MPhil student in the department of Comparative Literature at Ambedkar University Delhi.

Featured image source: Architectural Digest