Trigger Warning: rape and custodial violence

Mathura, a young tribal woman from Maharashtra, was reportedly raped by two uniformed police officers in 1972. Her trauma shook the country and changed the landscape of rape laws in India.

Background

The incident took place on 26 March 1972, in Desaiganj Maharashtra. Mathura, who at the time was between 14-16 years old, had developed a relationship with Ashok, a man who was related to her employer. As per customary practice of her tribe, Mathura had eloped with Ashok and was living with him. Mathura was an orphan and lived with her brother Gama prior to this.

“Among several tribes in the Western India- Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra, the live-in relationships between couples is a customary practice. Their culture of cohabitation is based on couple’s right to choose and right to reject. Bhils in Gujarat, Garasia, Gamar Community in Rajasthan who are subsisting on farming and manual labour have been extremely poor and deprived for centuries. They have traditionally been cohabiting under live-in arrangements, have children also and when they accumulate adequate marriage expenses, they get married. At times the head of the household organises group-marriages of 2 generations of live-in couples to economise the cost,” said Dr.Vibhuti Patel, women’s study scholar.

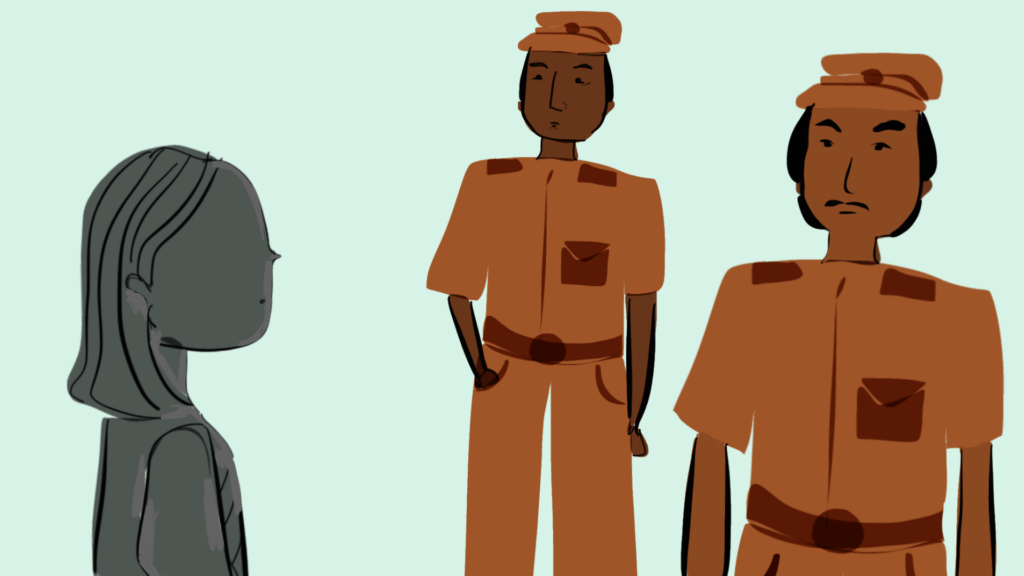

On the night of the incident Mathura was summoned to the police station regarding an FIR filed by her brother who disapproved of her relationship. After taking the statements of all concerned and asking everyone to leave—two police constables, Tukaram and Ganpat—asked Mathura to stay back.

It is reported that thereafter constable Ganpat took Mathura to a toilet situated near the back of the building, loosened her underwear and shined a torch over her private parts. He then dragged her to the main building where he pushed her to the ground and raped her in spite of stiff resistance on her part. After Ganpat, constable Tukaram also came over Mathura and fondled her private parts. He too tried to rape her, but was unable to do so because he was highly intoxicated at the time.

By this time Mathura’s family, who had been waiting outside the police station started to grow suspicious since the lights of the police station had been turned off and the entrance was bolted from within. They called out to Mathura but received no response, and the noise attracted a crowd near the station. After some time Mathura emerged from the station and informed the crowd that she had been compelled by constable Ganpat to undress herself and he had then proceeded to rape her. On hearing this the agitated crowd threatened to burn down the police station, and the head constable was forced to take down Mathura’s statement.

Also read: Jani Shikar: The Powerful History Of Adivasi Women Warriors

The case

Despite the power differential she decided to take this matter to court, and was able to do so as a young feminist lawyer, Vasudha Dhagamwar fought the case probono from 1972 to 1979. The case was first taken to a sessions court, which found the defendants not guilty. On appeal, the Bombay High Court set aside the judgment of the Sessions Court, and sentenced the accused to one and five years imprisonment respectively. The High Court judgement held that “Mere passive or helpless surrender of the body and its resignation to the other’s lust induced by threats or fear cannot be equated with the desire or will, nor can furnish an answer by the mere fact that the sexual act was not in opposition to such desire or volition.”

Despite the valid judgement by the High Court, which took a more holistic approach to consent, justice for Mathura was elusive. In September 1979, the Supreme Court overturned this judgement and pronounced the defendants not guilty.

The SC’s verdict was based on the following three arguments:

- Mathura did not vocally express her non-consent during the ordeal.

- There was a lack of bruising on her body.

- She was ‘habituated to sexual intercourse’ based on the ‘two-finger-test‘.

While the first two portions of the judgement become problematic in themselves it is the third part of the judgement that raises most cause for alarm. To begin with, the two finger test—which for the longest time was the method of checking whether or not a survivor was in fact raped—is a deeply flawed process. The test is conducted by inserting two fingers inside the vagina to check the elasticity of a survivor’s vagina and whether the hymen has been ruptured. Going by the number of fingers admitted, a doctor gives his opinion on whether a woman is “habituated to sex” or not. Secondly, to assume that a hymen can only be ruptured by sexual intercourse is medically incorrect. The test is not only unscientific but also illegal in India.

But more important than the medical inaccuracy of such a test is the taboo surrounding pre-marital sex. The test did not take into account cases of consensual intercourse, and by extension of that, neither did the courts. As is clearly demonstrated by this judgement, the presumption was that a woman is to only have sex after marriage, and any woman who chooses to have sex before she enters this state sanctioned institution, cannot possibly be at the receiving end of a crime such as rape.

The courts went so far as to say that since Mathura was ‘habituated’ to sexual intercourse, she perhaps initiated sexual intercourse, seduced the the police officers, and then came out and cried rape in an effort to seem’‘virtuous’ in front of her brother, and partner.

Civil Society response

A few days after the verdict was announced, four law professors, Upendra Baxi, Raghunath Kelkar, Lotika Sarkar and Vasudha Dhagamwar wrote an open letter to the Supreme Court protesting the concept of consent in the verdict. Important lines from the letter read “Is the taboo against pre-marital sex so strong as to provide a license to Indian police to rape young girls?“

Several protests and demonstrations took place in the country following this verdict, and this case is touted to be one of the cornerstones in the development of a national feminist movement in India. A number of women’s group were formed as a direct response to the judgment, including Saheli in Delhi, and prior to that in January 1980, in the formation of the first feminist group in India against rape, ‘Forum Against Rape’, later renamed ‘Forum Against Oppression of Women.’

When taking a look at Mathura’s case it becomes important to talk about the power structures at play. Mathura was an orphaned Adivasi teenager who was struggling to make ends meet. In her first recounting of the incident, Mathura said that the cops had threatened to file a false case and imprison her and her relatives if she did not do exactly as they said.

Lines from the open letter written to the Chief Justice of India, best explain the dynamics at play in the case:

“Your Lordship, does the Indian Supreme Court expect a young girl 14-16 years old, when trapped by two policemen inside the police station, to successfully raise an alarm for help? Does it seriously expect the girl, a labourer, to put up such stiff resistance against well-built policemen so as to have substantial marks of physical injury? Does the absence of such marks necessarily imply absence of stiff resistance?“

Legal Reform

Despite the large-scale opposition to the verdict in Mathura’s case, and demanding that it be reopened, the court still held that there was no legal standing in the case to rule in favour of Mathura. Eventually this led to Government of India to amend the rape laws in our country. In 1983, a new category was added to criminal laws dealing with rape.

- The law mandates that a court presume a woman who says she did not consent to sexual intercourse is telling the truth.

- Mathura’s case also led to in camera rape trials being conducted as closed proceedings and to a ban on identifying victims by their real names.

- Besides defining custodial rape, the amendment shifted the burden of proof from the accuser to the accused.

- It also demanded that before sunrise and after the sunset, women can not be called to the police station.

The never-seen-before protests that rocked India at the time of the Mathura rape case were about the tone and tenor in which the Supreme court spoke about the issue of consent – the manner in which morality and victim blaming was woven into the judgement.

Victim blaming and archaic ideas of sex and morality still form the basis of many judgements being made in our country. Acquitting Tarun Tejpal in a case of sexual assault against his former colleague the court held that the victim did not show signs of being a survivor of assault, in 2017 a two-judge bench of the Punjab and Haryana High Court awarded bail to three law students, even calling the survivor ‘promiscuous‘, in a 2013 judgement the Supreme Court said that victim was supposed to attack the appellant like a wild animal, but she did not even resist. The list goes on and on.

Although we are decades away from Mathura’s ordeal—an important question to ask is how far we have really come?

Also read: The Historical Journey Of Rape Laws In India

Featured Image Source: Women march in New Delhi in 1980 to demand that the Indian Supreme Court reconsider the case of Mathura, who accused two policemen of raping her when she was a teenager. The high court overturned the convictions of the two constables. Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images/File

About the author(s)

Nishtha is a former student of philosophy and enjoys discussions on ethics. She's currently a video journalist and wants to make films some day. When not working Nishtha can be found hoarding stationery, listening to ghazals and playing with her dog.