The Chhattisgarh High Court on August 25, discharged a man from facing trial for “allegedly” raping his wife. Justice N K Chandravanshi, who presided over the case, noted, “in this case, complainant is legally wedded wife of applicant No. 1, therefore, sexual intercourse or any sexual act with her by the applicant No. 1/husband would not constitute an offence of rape, even if it was by force or against her wish.” His observation was based on an exception to Section 375 of IPC which states that “sexual intercourse or sexual act by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape.”

The judgement, prima facie, carries a shock value and perhaps for most of us a chilling reminder of the limited bodily autonomy we have. While we expect our judiciary to take progressive and enabling readings of the law to shape a better society, it is worth introspection on how we understand consent.

The judgement, prima facie, carries a shock value and perhaps for most of us a chilling reminder of the limited bodily autonomy we have. While we expect our judiciary to take progressive and enabling readings of the law to shape a better society, it is worth introspection on how we understand consent.

Also read: Kerala HC’s Marital Rape Judgment Finally Shifts The Focus Away From ‘Sanctity Of Marriage’

In the aftermath of the #MeToo Movement, debates on consent took centre-stage. Many took to social media, newsrooms and editorials to pen down what consent is, detailing the ins and outs of the act of consenting. While it allowed us to move beyond the Cambridge Dictionary’s definition of consenting as simply the act of “permitting or agreeing to do something or allowing someone to do something”, what remained peripheral to discussion is who in the first place has the agency to consent.

To understand this better, one has to see the prerequisites that make you and I, capable of consent. The ability to consent to any act rests on the premise that participants in a given transaction are recognized not only legally but also socially as individuals. A legal recognition of individuality is the basic prerequisite for one to avail legal remedies in case of violation of one’s personhood; a social personhood implies that the society too sees you as an individual who has inalienable rights to one’s own body and that these rights are exercisable by you, and not by your family/kin/community on your behalf. While the legal recognition of individuality is relatively easier for most, social recognition of it is not so much.

The making of gender is at the outset, a project of obliviating individuality by moulding people into defined gender performances: a ripple effect of genders that we are moulded into is the right to choose and our ability to exercise it. The most fundamental way it operates is the way we are named and identified within our immediate societies. A male child is identified as both: son of his father but also as himself, and by the time the transition from boyhood to manhood completes, he is less of someone’s son and more of himself. Contrarily, a female child’s life, from birth to death, never revolves around her own identity. She is born as the daughter of someone, becomes the sister of someone, marries to be the wife of someone and dies as the mother of someone. More often than not, the “someone” tends to be a male figure.

The transitions in a female’s identity outlined above are not mere social markers, they are also indicators of who exercises agency on her behalf at different stages. What one sees is incremental relinquishing of agency and by extension the ability to consent, socially and legally by the woman. Parallel to this, the male child, at the end of boyhood, reclaims all agencies exercised by his father and thus becomes a legal and social individual who has the agency and ability to consent.

Also read: Criminalising Marital Rape: The Pandemic Has Women Locked Down With Their Abusers

The Chhattisgarh High Court judgement of August 25 stems from this social undercurrent. When an unmarried or married woman is sexually assaulted by a man who is not her husband, the Court and the legal system by extension, argue that it is a “grave crime against the society”. The emphasis that it is firstly a crime against society before a crime against the survivor reinforces who is the agentic party in this act and thus, who has been violated. In a similar vein, the Chhattisgarh High Court’s judgement upholds the patriarchal moulds of our society that a wife has no agency and if any is available, it is to be exercised, primarily by her husband and then her kin.

While a lacuna remains in legislative and judicial response to the trauma and silent suffering of marital rape, there is also a gigantic task ahead of us. Of creating an enabling society that recognizes the personhood of women beyond legal tenets. One that calls her by her name, not someone’s someone.

While a lacuna remains in legislative and judicial response to the trauma and silent suffering of marital rape, there is also a gigantic task ahead of us. Of creating an enabling society that recognizes the personhood of women beyond legal tenets. One that calls her by her name, not someone’s someone.

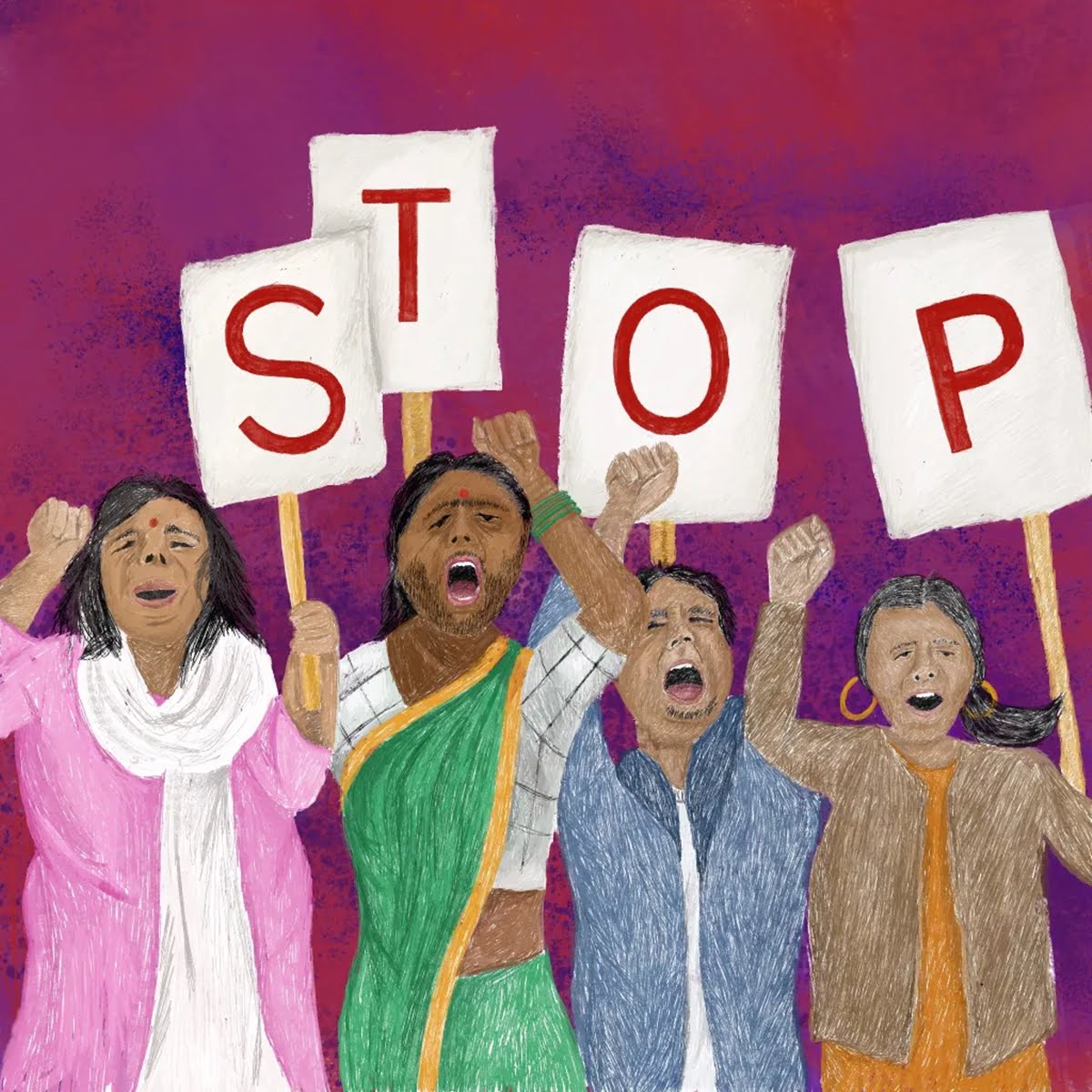

Featured Image Credit: Aasawari Kulkarni/Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.