Netflix dropped the entire third season of their critically acclaimed and wildly popular original, Sex Education, on September 17. Like many of its fans, I managed to devour this season in a day and was beyond impressed at the breadth and depth of storytelling that the creator, Laurie Nunne, decided to share with the world.

The show follows the lives of several British young adults at the fictional Moordale High, as they come to terms with their sexualities, relationships (romantic or otherwise), and their place in this world. Known for its thoughtful representation, eccentric wardrobes, and stereotype-defying storylines, I feel proud that this iteration has managed to remain narratively fresh.

In a season filled with some really contrasting story arcs, there was one writing choice that was so genre-defying and so consistent in its desire to bend creative boundaries that it cannot be written off as accidental, that is worth highlighting – especially from a feminist perspective.

Also read: Netflix’s Sex Education: Season 3 Shows The Radical Power Of Sex & Education Coming Together

Unlike many of its predecessors and peers, this show manages to portray men as working on themselves – particularly their sensitivity in relationships – as celebratory, whilst withholding a perfect relationship as a reward for having improved.

Before I get into it, I must warn you that this is a spoiler-filled analytical review, so it’s worth watching it all before reading on.

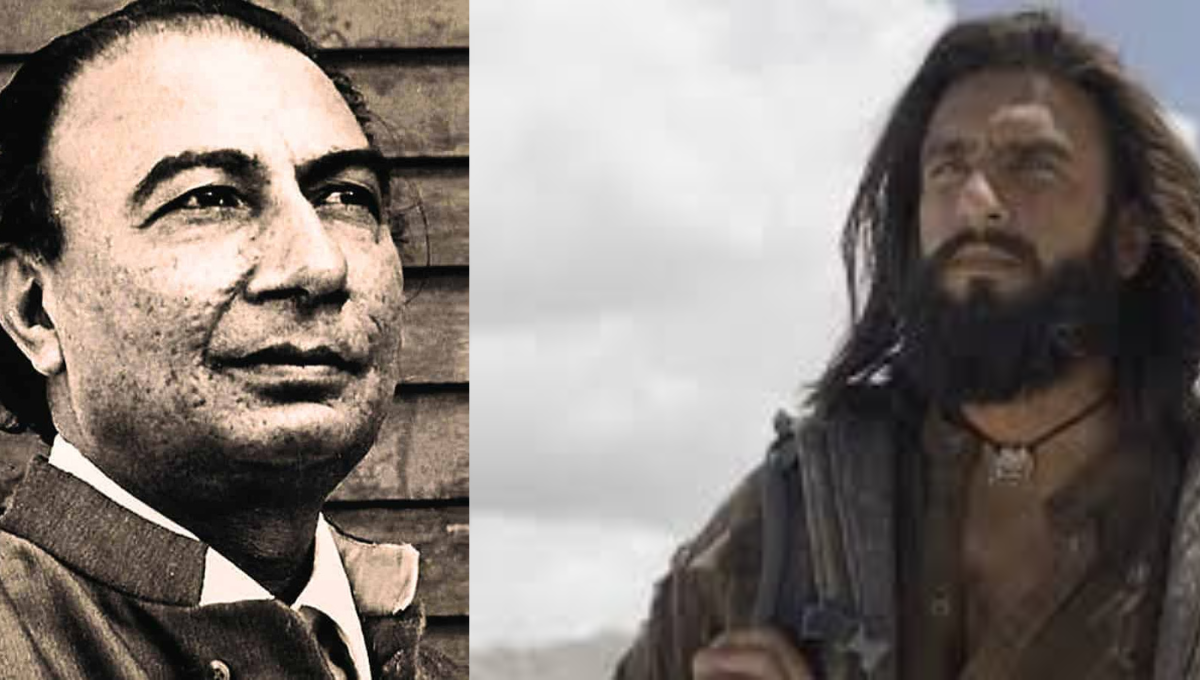

Sex Education is essentially a coming-of-age story, with a strong emphasis on sexuality and relationships. This genre of stories – think Breakfast Club or Tamasha, more recently – has cemented a connection between growth and romance in their storylines. In Tamasha, a stark example, Ved overcoming his borderline personality disorder is very vaguely suggested as some kind of sudden spiritual encounter and the story ends with an obvious hint that he would go on to romantically re-connect with Tara. There is no emphasis on the work it takes to better oneself, regardless, the romantic reward is guaranteed.

In Tamasha, a stark example, Ved overcoming his borderline personality disorder is very vaguely suggested as some kind of sudden spiritual encounter and the story ends with an obvious hint that he would go on to romantically re-connect with Tara. There is no emphasis on the work it takes to better oneself. regardless, the romantic reward is guaranteed.

This formula is pervasive. A romance (or even the prospect of one) is presented like a reward, to be granted after the arduous journey that the protagonist makes through the story. More worryingly, this trope is applied heavily along gendered lines. Female-oriented stories – like Queen, Lipstick Under My Burkha and Hollywood’s Booksmart – often focus away from the romance at the end, whilst male-oriented ones – like Dil Chahta Hai, Tamasha – almost certainly end on the prospect of one.

Though seemingly innocent, this trope might have inspired a more sinister/reductive pattern of understanding men (or manhood). Take this tweet for instance, where several comments assume that men only behave empathetically towards women when they wish to be romantically/sexually involved with them. A mere sign of professionalism is reduced to the desire to obtain sexual gratification – a patriarchal mode of thinking that deliberately misconstrues men’s humanity and empathy.

In Sex Education, successful romantic relationships have understandably been a focal point; whether we experience romance or not, the crowds do indulge in stories about them. There’s Maeve (Emma Mackey) and Otis (Asa Butterfield) with their nail-biting ‘will they, won’t they?’ arc; there’s Eric and Adam’s wildly contrasting aesthetics and backgrounds; there’s new entrants Cal and Jackson, and many, many more.

This season, the ‘opposites-attract’ factor that underpins many of these romances was demystified, as individual plotlines began to reveal the discrepancies between the pairs. If the relationship must work, these needed to be overcome.

There was particular emphasis on showing the underdog male characters – (former) Headmaster Groff, Adam, Jackson, Steve and Otis – as willing to put in more effort into themselves and learn to do The Right Thing™ – an action they hoped would be enough to reinvigorate the relationship. This was interestingly explored in the case of Jackson. His love interest, Cal, is nonbinary and points out that they don’t want Jackson to perceive them as a girl, which he readily admits to. After some deliberation, Jackson shows a decisiveness to learn more about Cal’s identity and being in a “queer” relationship. This character recognised that there’d be work involved and was ready for it.

Interestingly however, Cal rejects Jackson, because they want to focus on their own journey of self-discovery. The term ‘rejection’ feels a tad wrong for the circumstances. Rejection tends to imply that the person each guy wanted did not have any romantic feelings towards them. In fact, each dumper – Maeve, Aimee, Cal, Eric and Mrs Groff – appreciate and return the romantic advances of their partners, but ultimately choose to prioritise a need to grow unattached and unencumbered. The ‘rejections’ are brought about so organically in each case, that I did not notice that a pattern of independent growth is being championed in the season, until I reflected on it a few days later.

In Sex Education, each dumper – Maeve, Aimee, Cal, Eric and Mrs Groff – appreciate and return the romantic advances of their partners, but ultimately choose to prioritise a need to grow unattached and unencumbered. The ‘rejections’ are brought about so organically in each case, that I did not notice that a pattern of independent growth is being championed in the season, until I reflected on it a few days later.

It was undeniably heart-breaking to watch the couples I’d grown fond of and often projected my own desires onto, end their relationships (or refuse to embark on them despite the killer chemistry).

But it has to be acknowledged that vital character development would have been squandered if the season had ended with any of these couples choosing to be together. Watching this eclectic mix of young and older women, and Black and queer people make tough decisions about developing themselves was strangely relieving. Furthermore, the willingness to detach male self-improvement from romantic reward was so refreshing and reminded one that coming-of-age is truly about much, much more than romance. Indeed, men’s humanity and empathy should neither be belittled, nor excessively rewarded, but simply understood as it is – growth for the sake of growth.

It’s not every day that a show beloved by the masses honours authentic character trajectories – especially for marginalised identity characters – and risks a few disappointed male characters. Although I’m still rooting for many of these couples to get back together, I’m far more excited to see the individual character trajectories blossom further and I have Sex Education’s writing team to thank for that. It’s just too bad that they haven’t helped me at all with how impatient I am for the next season.

About the author(s)

Richa is talkative, argumentative but, above all, loves all things feminism.