Amma bought me my first brassiere like all mothers have to. It was a short intimate moment. She clasped this new addition to my body and its cups deflated on my chest. She said that it was time and I had to be more careful of boys now. I felt new, even though my chest hid under three layers of cotton looked strangely unappealing. I navigated life slowly under Amma’s maternal prowess guiding me through the battle of thickening breasts and slow hair eruptions. We grew up together as one world in the same household under the provoking of the same men. Little did she know that I grew up a little too fast and kept falling in love with women, even though she had only warned me about boys. I want to come out to Amma, but I also cannot. It remains an itch on my back, like the ones that we cannot properly reach.

Now, how do you treat an itch? I decided to poke it a little and my weapon of choice was a movie from the 1980s that Amma and I watched together. Deshadanakilli Karayarilla (translation: Migratory Birds Don’t cry) is an Indian Malayalam language film by P. Padmarajan and also the first queer film that my Generation Z self watched in the language I speak. The film introduces Nimmy and Sally, two best friends who take off from a school picnic to find the odds of the world, and to find what Sally terms a “safe place”. I wanted to ask Amma if she thought the green-eyed gum-chewing Sally was lesbian? Or if Sally and Nimmi had a little more than friendship? I wanted to know how she would react if I poked and prodded her about same-sex relationships, to see if the “safe place” that Sally was looking for is right before me.

Also read: Deshadanakili Karayarilla: A 1986 Malayalam Film That Attempted To Portray Queer Teenage Life

Thematically, the film explores desire, but not particularly queer desire or erotic desire. Perhaps the lack of sex or explicit desire in the film is why many deny the film to have queer intentions. Deshadanakilli Karayarilla explores desire in the garb of safety, an important element that we hope to bestow on anyone who comes out of the closet to their friends, family or to the world.

What P Padmarajan does through the film is construct a metaphor for the closet. He creates a landscape for two schoolgirls, undeniably in love, bolting from adults who persistently arbitrate their attempts at finding a safe space to come out to each other. In another sense, the film is not about queer love, but about queer love denied.

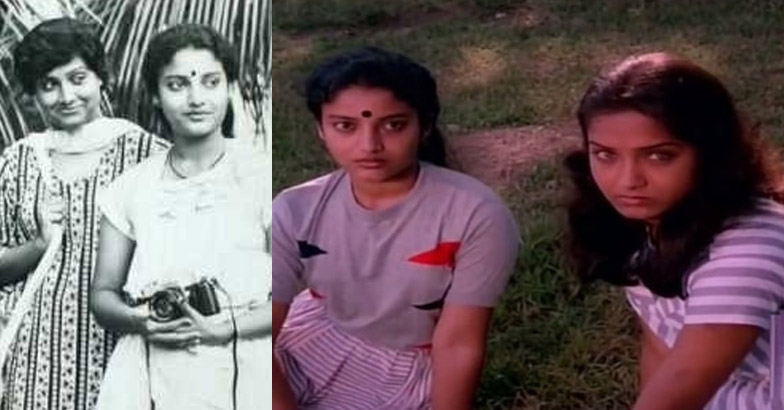

The on-screen portrayal of homosexuality in Malayalam cinema was not prominent before the 1990s. New age films explore queerness with more veracity but lack the nuances of queer love like friendship, heartbreak and acceptance. This is why I had to unearth this gem from the 1980s, not simply because it deserves due credit, but because it functions as a buried time capsule that could bridge queer meaning over two generations. Sally and Nimmy, though portrayed as best friends, are put against the same backdrops that lovers in Malayalam films are made to. Falling in love usually ensues a song, the camera focuses only on the two lovers while the world around them begins to blur for the viewer.

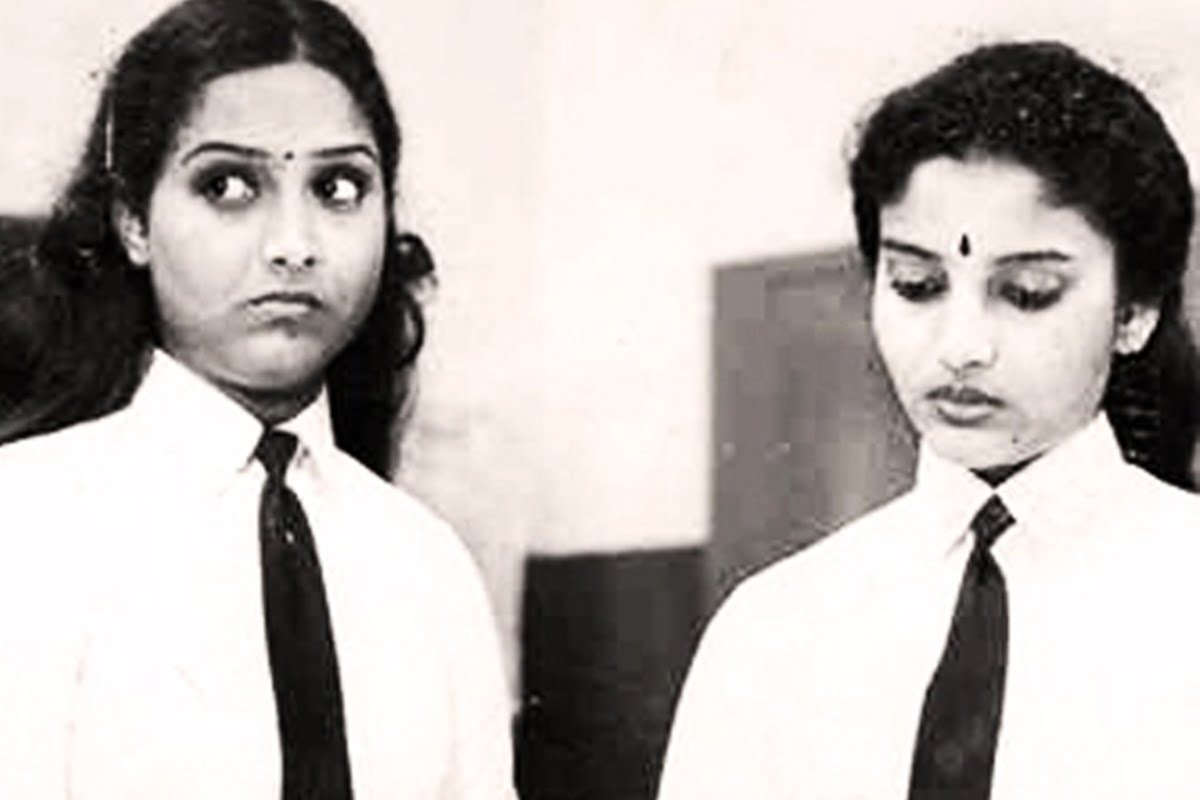

The song ‘Vaanampaadi Etho’ penned by O. N. V and sung by K J Yesudas does this, but instead of the expected heterosexual couple, we get a montage of Sally and Nimmi working against the world as one thick globe. It is at this point that the film becomes threatening. P Padmarajan ensures that the actors Shari and Karthika who play Sally and Nimmi have the potential to become typecast lovers and therefore destroy the Malayalee palate for men and women falling in love, again and again on screen. A viewer would hope to see them be cast the same way again, and this hunger to see queer love on screen is why Deshadanakilli Karayarilla is an itch on your back, a method of picking apart society’s appetite for compulsory heterosexual romance.

P Padmarajan ensures that the actors Shari and Karthika who play Sally and Nimmi have the potential to become typecast lovers and therefore destroy the Malayalee palate for men and women falling in love, again and again on screen. A viewer would hope to see them be cast the same way again, and this hunger to see queer love on screen is why Deshadanakilli Karayarilla is an itch on your back, a method of picking apart society’s appetite for compulsory heterosexual romance.

Sally and Nimmi live as hideouts, taking refuge in a youth hostel under different names, altering their appearance and doing odd jobs at antique stores. Their school puts out a search for them but it is quite easy for two odd girls to get ambiguous in the waves of Cochin port, India. Sally is tormented by the fear that she is followed which is not irrational because strange men seem to follow them relentlessly. Two men lurk around them on the first day on their own. The women talk in English to avoid being understood, pretend to belong and escape on an autorickshaw to town.

At town, they get followed again by a policeman who is suspicious about two girls going about late evening without a man accompanying them. Quick-witted Sally tells him that they are sisters and need an auto which he helps arrange for them. He also unnecessarily accompanies them to their fictional friend’s convent hostel because the thought of two girls alone at night is a space that self-righteous men like him love to invade.

Also read: Montero & Take Me To Church: The Pride And The Peripeteia Of Paradise

Perhaps it is the constant trespassing of men in their personal space that causes Nimmy to place trust in Harishankar, a character played by Mohanlal, who although knows the girls are hiding their identity never reports them to the police. Nimmy, like the many women I know, takes refuge in one man to evade the prowling of many others and thus she falls in love. When Sally realises that Nimmy has fallen in love with Hari she assures Nimmy that to be loved and to love is one of the greatest blessings in the world. This is the point at which Sally proves to be the better lover, one that bends her rules for an imagined safe space that she has not yet found but is ready to provide it to Nimmy.

In Deshadanakilli Karayarilla, When Sally realises that Nimmy has fallen in love with Hari she assures Nimmy that to be loved and to love is one of the greatest blessings in the world. This is the point at which Sally proves to be the better lover, one that bends her rules for an imagined safe space that she has not yet found but is ready to provide it to Nimmy.

If I ponder more about my own queer relationships, coming out is a repeated event and the demand to come out is always dissolved in the safety of the one you are in love with. Sally is denied an exit from the closet and she willfully avoided it, to keep Nimmy safe. If Sally had come out to Nimmy fearing the looming threat of Hari, she would have either lost Nimmy or would have taken away something that Nimmy deeply wanted. Sally is denied her identity by forces like her conservative school, family and men like Harishankar and Devika teacher. Her agitation is expressed when she lashes out on her teacher, calling her a “bitch” for trying to take Nimmy away from her. Sally and Nimmy are two closeted teenagers and Deshadanakilli Karayarilla can possibly be the first queer film in the Malayalam language.

Two generations have watched and re-watched this film and only recent developments have brought attention to its queer nuances to the attentive malayalee. Yet, the film is denied its queer intentions due to the lack of open disclosure about homosexuality or sexual innuendoes between Nimmy and Sally. Like I remarked before, the film is a time capsule to be found by closeted queer persons today, one that is a conversation starter to come out to a parent who grew up in the 1980s and know only the absence of homosexual relationships. The question, “Amma, do you think Sally is a better lover than Hari?” followed by a sudden gasp of “eh? What are you saying?” is quite enough to know where your safe place is, far far away or maybe, right here.

Sharon(she/her) is a literature graduate from the University of Hyderabad currently working on her research proposal even though a nice long gap from academics will do her good. But, she never listens to her own advice and spends most of her time being anxious. Her life is full of queerplatonic relationships and she can’t seem to stop writing about love and loss. In her free time, she reads photographs and writes long emails. You can find her on Instagram and WordPress.

Featured image source: IFFK

About the author(s)

Sharon is a staff writer for FII.