There is a famous saying that Mard ko dard nahi hota (Men do not feel pain). Pop culture has portrayed that men do not feel any pain, and at the same time, women are overtly emotionally expressive when in pain. On the contrary, research has shown that it is women whose pain is perceived as lesser than men. Caroline Cridao Perez, in her work Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in A World Designed for Men illustrates how the systemic inequalities related to gender and their vast magnitude.

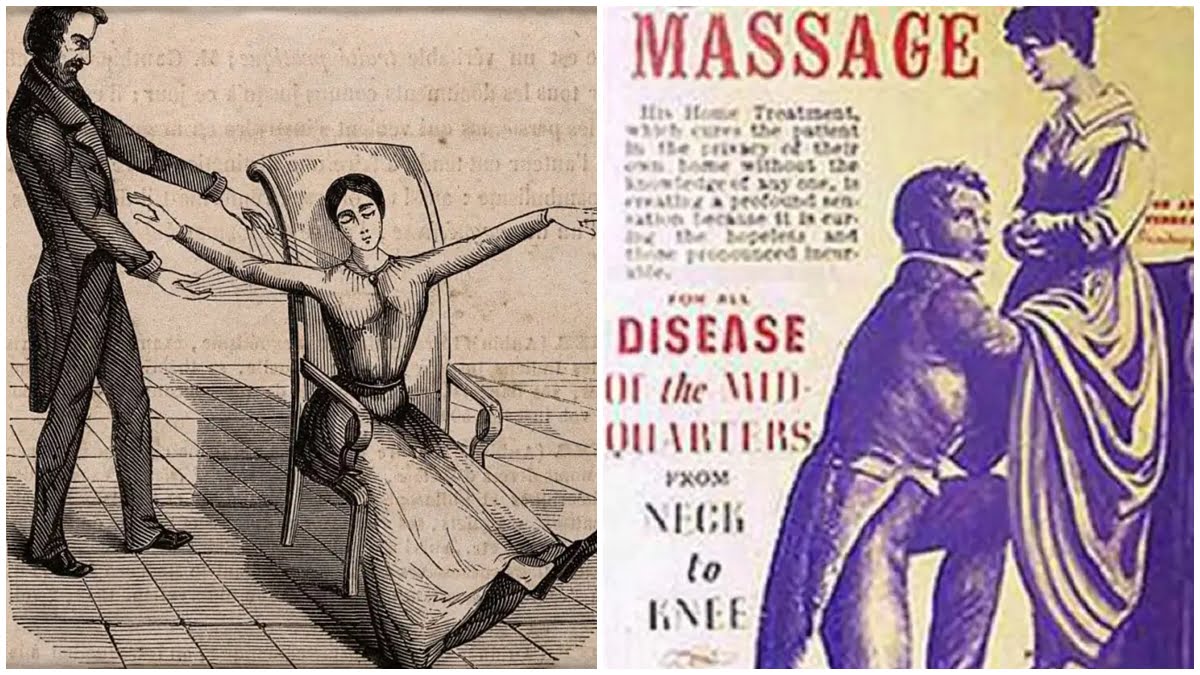

One of these inequalities leads to ‘Yentl Syndrome’ – the misdiagnosis of women unless they have symptoms as shown by men. The name comes from the 1983 film Yentl, where Barbara Streisand plays a woman pretending to be a man. When women say they are in pain, they are labelled as mad. Since the Greeks, women have been considered hysterical (hystera is the Greek word for the womb). This has been satirized by Taylor Swift in her song Blank Space and Netflix in the show Crazy-Ex Girlfriend. Historically, women’s mental health treatment has been met with the unnecessary incarceration of years in asylums and their pain is far more likely to be dismissed as ‘emotional’ or ‘psychosomatic.’ They are prescribed antidepressants when they are not even suffering from depression.

‘Yentl Syndrome’ is the misdiagnosis of women unless they have symptoms as shown by men. The name comes from the 1983 film Yentl, where Barbara Streisand plays a woman pretending to be a man. When women say they are in pain, they are labelled as mad.

Studies had also shown that when men and women reported pain, men were given pain medication, and women were given sedatives or antidepressants. Not only do men and women experience pain differently, but women’s pain might also increase or decrease through their menstrual cycle. They have more significant waiting times than men. In fact, a woman suffering from a heart attack will wait one hour longer than a man from the onset of pain to arrival at the hospital. To put it succinctly, the average general practitioner has no idea that drugs like paracetamol and morphine have differing impacts on women.

Pain is influenced by biological factors, like muscle pain sensitivity. Cultural aspects impact the understanding too, for instance, the way physicians treat pain in women and men patients can depend on the gender of the physician. Research also suggests that gender stereotypes impact the way men and women report pain. Painful conditions like endometriosis can go undiagnosed in women for years. Even though women have claimed to change the narrative in pop culture through shows like Fleabag, which had a long monologue on women and pain, it is crucial to understand that this monologue of pain and resilience contains notions of biological essentialism, and reeks of trans misogyny. It points out that women suffer because they are biologically predetermined. According to Plaidos, it fails to account for the myriad of social, cultural, and economic factors.

Also read: Tracking The Painful Credibility Deficit Of Women

The Lack of Representation Of Women’s Anatomy in Medical Textbooks

The Ancient Greeks saw the female body as a ‘mutilated male’ body, and ovaries were initially known as female testicles. The male body has been thought of as anatomy itself as the males of the Caucasian population have been considered as the “norm” to study population, leading to male bias as researchers thought that women would have the same response as men to diseases. Even today, sex and gender issues are not addressed in curriculum development, and ‘gender-neutral information’ represents half of the male world. The failure to include women in anatomy textbooks is due to the historical perception of the male body as ‘the default’.

Sex and gender are distinguished for analytical purposes, but one must understand that they also interact to form individual bodies, cognitive abilities, and disease patterns. Sex itself is not as simple as a binary of male-female. It is so complex, so much so, that beyond the X and Y chromosomes, a full third of our genomes behave differently in men and women. For years, physicians have referred to women’s healthcare as “bikini medicine” because women’s bodies are treated the same as men, leaving aside the parts that could be covered with a bikini (the sheer misogyny and sexism here is appalling).

Stemming from this understanding of sex and the human body, the idea of “women’s health” has been understood as only reproductive health. Now, it incorporates women’s distinctive biology, which involves studying diseases that are unique to women, have a higher prevalence in women, or show different symptoms for women.

The Lack of Understanding of Women’s Health

Perez shows how women are given dosages as per men’s average weights and metabolisms. To take a case in point, women from poorer socio-economic backgrounds are 25% more likely to develop heart diseases. Furthermore, even though the lifetime risk is the same for both men and women, women tend to develop the risk 5-10 years earlier than men, highlighting the need for sex-specific research. Only recently, research has started to grapple with how women show differing results from men to clot-busting drugs or undergoing specific heart-related medical procedures.

Studies have shown that the immune systems of men and women respond differently to different infections due to genetic factors. Also, women might have evolved a swift and robust immune response, which at times can attack the body, leading to more women developing autoimmune disorders. A woman’s reactive immune system leaves her more susceptible to autoimmune diseases and allergies. Of all those affected by autoimmune diseases, 78% are women.

The lack of emphasis on women’s health includes men being considered cheaper for trials and women’s oestrous cycle constructed as a hurdle. Researchers say– we lack comparable data, female bodies are too complex or too costly to be tested on, and gender integration in research is burdensome. They even go as far as to say that it is difficult to recruit women for clinical trials due to their care-giving responsibilities. Conversely, women are also at the risk of overtreatment in reproduction areas like unnecessary caesarean sections and hysterectomies and these differences become more acute with different ethnicities.

The Exclusion of Women from Clinical Trials

Women are included in trials when their hormone levels are the lowest (early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle) or when their hormone levels are similar to that of men. This ignores how menstrual cycles have impacted findings on antipsychotics, antihistamines, and antibiotic treatments. Women’s menstrual cycles have been used as excuses to keep them excluded. They are often overdosed, perceived as more sensitive or prescribed multiple medications as their symptoms are matched with those of men. This is even though researchers have mentioned that it is crucial to understand drug disposition and its regulation as per sex differences.

Women are excluded from another crucial clinical trial – one related to sports science. The exclusion becomes visible with how most of the research on traumatic brain injury is done on men, even though women suffer concussions more. Consequently, female athletes are less likely to be adequately treated. The gender bias in sports science has been historical. Women are also under-represented in exercise in science (same excuse of the menstrual cycle). By extension, it is not just biological reasons; there are cultural reasons like female athletes getting less TV time, pay, and recognition than men, leading to less funding that impacts them directly.

Women are excluded from another crucial clinical trial – one related to sports science. The exclusion becomes visible with how most of the research on traumatic brain injury is done on men, even though women suffer concussions more. Consequently, female athletes are less likely to be adequately treated. The gender bias in sports science has been historical.

Women are also more likely to report asymptomatic symptoms of depression. Even though women have higher chances of suffering from depression than men, animal studies are five times more likely to be done on male animals. There is also a high prevalence and overall cost of depression for women, substantiating the urgent need of inclusion of women in clinical trials. The involvement of women does not mean mere enrolling in clinical studies; it includes planning, designing, and conducting clinical research integrating gender, considering both sexes. Failure here leads to the generalisation of the results of studies conducted on males to females, leading to serious breach of ethics. Accessibility to clinical trials is also crucial as it impacts women and gender minorities disproportionately.

Also read: The History Of ‘Hysteria’ And How Science Can Be Sexist

Feminist Approaches to Health: Towards A Shift From Binary to Intersectional

The advancement in women’s health and research would require critical, collective support from policymakers, healthcare professionals, advocacy organisations, and funding organisations to promote health equity. Feminist reforms in biomedicine have also been attacked because of women’s higher life expectancy or other illogical reasons. With the argument of higher life expectancy, it is missed that even with higher life expectancy, women spend more significant years of their lives in ‘ill health.’

The Dutch Gender and Health Knowledge Agenda, calls for a “sex and gender-aware research methodology.” It traces a shift from ‘the binary’ to ‘the intersectional,’ focusing on epidemiology, pointing towards the areas that need rectification and urgent intervention. Feminist researchers are pushing for a “community” or “social” mode of investigation for evaluation of women’s health as opposed to the dominant “biomedical” model of research. Merely increasing the number of women in medical professions oversimplifies and depoliticizes a complex cultural process, highlighting the need for a multidimensional process of social change which requires support from both men and women.