A Woman Killed With kindness is a critically acclaimed seventeenth-century domestic tragedy by famous English dramatist Thomas Heywood. It which deals with the themes of murder, adultery, honour, friendship, kindness, virtue and debt, with the artistic employment of double plots.

Although several twentieth-century scholars including T.S. Eliot criticised the absurdity of the sub-plot, Freda L. Townsend, in her paper The Artistry of Thomas Heywood’s Double Plots, mentions that the main plot and the sub-plot complement each other adequately to reflect class and monetary conflicts, but most importantly, in the way the play treats its women characters.

The story of A Woman Killed With Kindness opens with John and Anne Frankford celebrating their marriage ceremony with friends and relatives. The play’s narrative revolves around a houseguest named Wendoll, who takes advantage of John’s generosity to entice Anne into infidelity. On discovering the truth, Frankford decides to isolate his wife from everyone else, including their children.

Consequently, Anne’s guilt and alienation put her on a devastating road of self-inflicted punishment. This storyline is juxtaposed with a subplot concentrating on Sir Charles Mountford and his “chaste” sister Susan, who opposes her brother’s attempts to utilise her sexuality to help him get rid of his debt to Sir Francis Acton.

Numerous connections can be drawn to demonstrate how the two plots are intertwined with each other. Throughout the whole play, class conflicts are made evident in the main plot concerning the middle-class Frankford household, but it becomes more conspicuous with the decline of the status of the aristocratic Mountford in the society once he is neck-deep in debt.

Symmetry can be drawn between the two plots as Charles Mountford and John Frankford both kill people, albeit, the latter does it passively with “kindness“. Also, by the end of the play, both Francis Acton and Anne Frankford find ways towards making amends to those they had wronged and seek to redeem themselves.

Although, all patriarchal cultures treat their women as commodities to different degrees, as a modern-day reader one simply cannot ignore the horrifying extent of it in A Woman Killed With Kindness. It is quite intriguing to note that from the beginning, the idealisation and treatment of Mistress Anne Frankford as the “perfect wife” who is “meek and patient“, and her sudden fall from grace to a “strumpet” as she commits adultery, can be said to reinforce the Goddess and the whore dichotomy that women of all centuries and nations have been subjected to, quite inevitably

It is easy to draw parallels between Susan who is determined to kill herself rather than be raped, and Anne who is resolute in her decision to seek redemption through self-starvation. Also, the recurring theme of debt that occurs in the Mountford plot where Charles insists on settling his obligation to Acton echoes in resonance with Wendoll’s inability to meet Frankford’s debt of gratitude in the main plot.

The two interwoven plots which bring together almost all the important characters in the play in the opening scene as well as the closing scene show Heywood’s narrative continuity and thematic purpose.

However, most important of all, in both the main plot and sub-plot, the treatment of women as a commodity, and the indication that the gateway to all resolutions is somehow related to the chastity of a woman, is difficult to ignore. The main plot also resonates with the sub-plot in its depiction of male friendships and how communities of men do not only exclude women from the narrative of decision making entirely, but also seem to have no qualms about using women as their most valuable form of capital for strengthening bonds between men.

Also read: Are Marriages Made In Heaven?: An Analysis Of Henrik Ibsen’s Iconic Play ‘A Doll’s House’

While in the sub-plot, the commodification of Susan is quite distinct when her brother Charles Mountford offers her “chaste honour” to Acton as a means of repayment of his debt, in the case of Anne, it is more of a symbolic nature as her chastity is supposed to be the jewel of Frankford’s honour. Susan’s value to her brother is in the form of actual capital, while the latter’s price to her husband is chiefly symbolic.

Although, all patriarchal cultures treat their women as commodities to different degrees, as a modern-day reader one simply cannot ignore the horrifying extent of it in A Woman Killed With Kindness. It is quite intriguing to note that from the beginning, the idealisation and treatment of Mistress Anne Frankford as the “perfect wife” who is “meek and patient“, and her sudden fall from grace to a “strumpet” as she commits adultery, can be said to reinforce the Goddess and the whore dichotomy that women of all centuries and nations have been subjected to, quite inevitably.

Another fascinating thing to observe here is the contrast in the ways of repentance between a woman and a man, for the same offence. Wendoll decides to go away to foreign countries, mourn, and only return once he recovers. However, Anne on the other hand, prioritises her husband’s forgiveness on Earth over a long life. Perhaps in Heywood’s drama, the only path to redemption for a woman is through her death

As Lyn Bennett says in her paper, it is important to note that married and unmarried women play different roles in Heywood’s drama. Before marriage, Susan is eligible to be exchanged as a commodity for her brother to retain his house and repay his debt to Acton. However, after marriage, a woman becomes an ideal property whose value belongs solely to her husband, as this is made evident in Anne’s case.

From this, it can be further deduced that adultery in the seventeenth century was not just about unfaithfulness and heartache. It was rather a matter of public disgrace and ridicule. It is consistently mentioned by Frankford towards the end of the play that their children’s names would be tainted because of Anne’s transgression.

Heywood shows that a woman’s infidelity was not just a moral issue, but an opportunity for the patriarchal society to take a dig at the husband’s manliness.

One would also find it interesting to note that although Acton later fell in love and married Susan, initially, he wanted to humiliate her by treating her as a means to exact revenge on Mountford. Susan’s virginity is not only treated as a prize to be given but also as an “object” to be taken to hurt her family’s “honour”.

Another fascinating thing to observe here is the contrast in the ways of repentance between a woman and a man, for the same offence. Wendoll decides to go away to foreign countries, mourn, and only return once he recovers. However, Anne on the other hand, prioritises her husband’s forgiveness on Earth over a long life. Perhaps in Heywood’s drama, the only path to redemption for a woman is through her death.

The hypocrisy of the society that Heywood has portrayed through A Woman Killed With Kindness is quite self-explanatory. A man’s act of forcing his sister to sacrifice her chastity and autonomy while objectifying her to be prized “above a million“, to serve his own agenda and egotistical sense of “honour“, is considered a sacrifice.

However, a woman committing adultery, albeit unjustifiable, but consensually, is labelled a vamp, exiled, and has to die by self-starvation to receive “forgiveness” from a man. This is a reflection of the patriarchal gender norms that the society mandates for men and women. Even today, far ahead of the seventeenth century, the themes in the play hold true with respect to how women are perceived and treated by the society.

Also read: Nationalism And Motherhood As Symbols In J.M. Synge’s Evocative Play ‘Riders To The Sea’

References:

Wiggins, Martin. A Woman Killed with Kindness and Other Domestic Plays. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Bennett, Lyn. “The Homosocial Economies of A Woman Killed with Kindness.” Renaissance and Reformation, vol. 36, no. 2, 2000, pp. 35–61., doi:10.33137/rr.v36i2.8606.

Heywood, Thomas, and Margaret Jane Kidnie. A Woman Killed with Kindness. Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2017.

Lisa Hopkins, The False Domesticity of A Woman Killed with Kindness. Connotations, 22 Sept. 2019.

Kidnie, Margaret Jane. “We Really Can’t Be Doing 1603 Now. We Really Can’t’: Katie Mitchell, Theatrical Adaptation, and Heywood’s A Woman Killed with Kindness.” Shakespeare Bulletin, vol. 31, no. 4, 2013, pp. 647–668., doi:10.1353/shb.2013.0068.

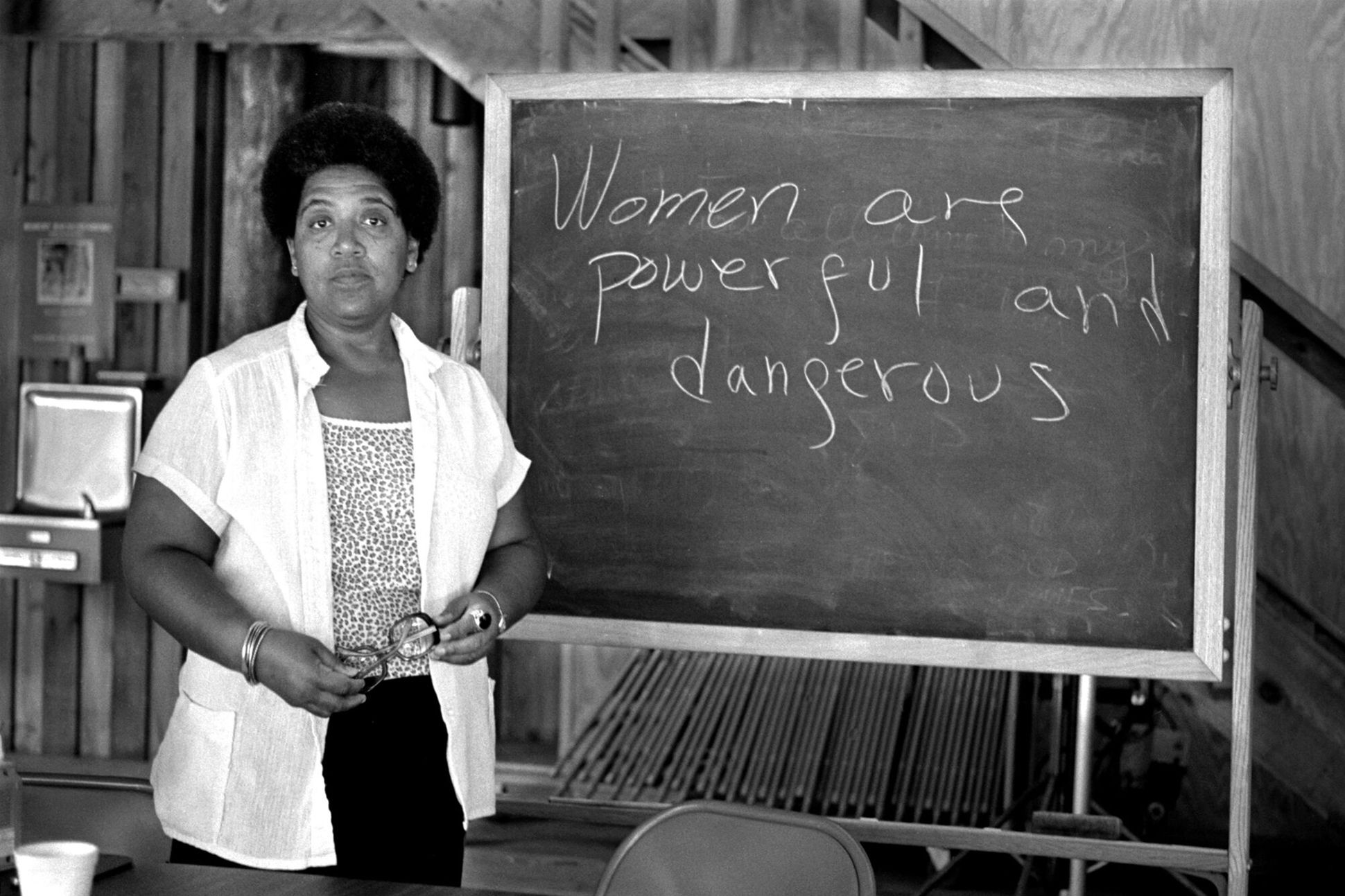

Featured Image: From Kate Mitchell’s production of A Woman Killed With Kindness, Dan Rebellato

About the author(s)

Poulomi is a Master's scholar from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, who loves to scribble poetry and write essays just when she can't seem to hold it all in. Her research interests include feminist studies, postcolonial theory, trauma and disability studies. She is very eager to read anything she can get her hands on, when she is not obsessing over spicy food or sleeping