A recently leaked document from the US Supreme Court has created quite a stir world over. The leaked papers seek to make abortion illegal by overturning the 1973 landmark case — Roe versus Wade; although the Supreme Court has affirmed that the decision is not final. So, what is the Roe v. Wade judgment, which the leaked document claims is ‘egregiously wrong from the start?

Basically put, the Roe v. Wade judgement can be considered a comprehensive document regarding abortion. Society is sexist, and at the beginning of the judgment, the Supreme Court made the remark that abortion is a difficult issue to deal with, embodying sensitive, emotional and, often, patriarchial opposing concerns that keep even the medical practitioners divided let alone the general public. Apart from questions of philosophy, theology, science, morality, choice, population growth, poverty, and other social and economic factors, it may further complicate the debate around abortion.

In the same breath, the Court reiterated that it would seek to find a solution to the discourse free from the above concerns in a constitutionally sound manner to incorporate “fundamentally differing views”. For this, the Court delved into a deep analysis of the history, science, ethics, opinions, laws, etc., around the sensitive issue of abortion.

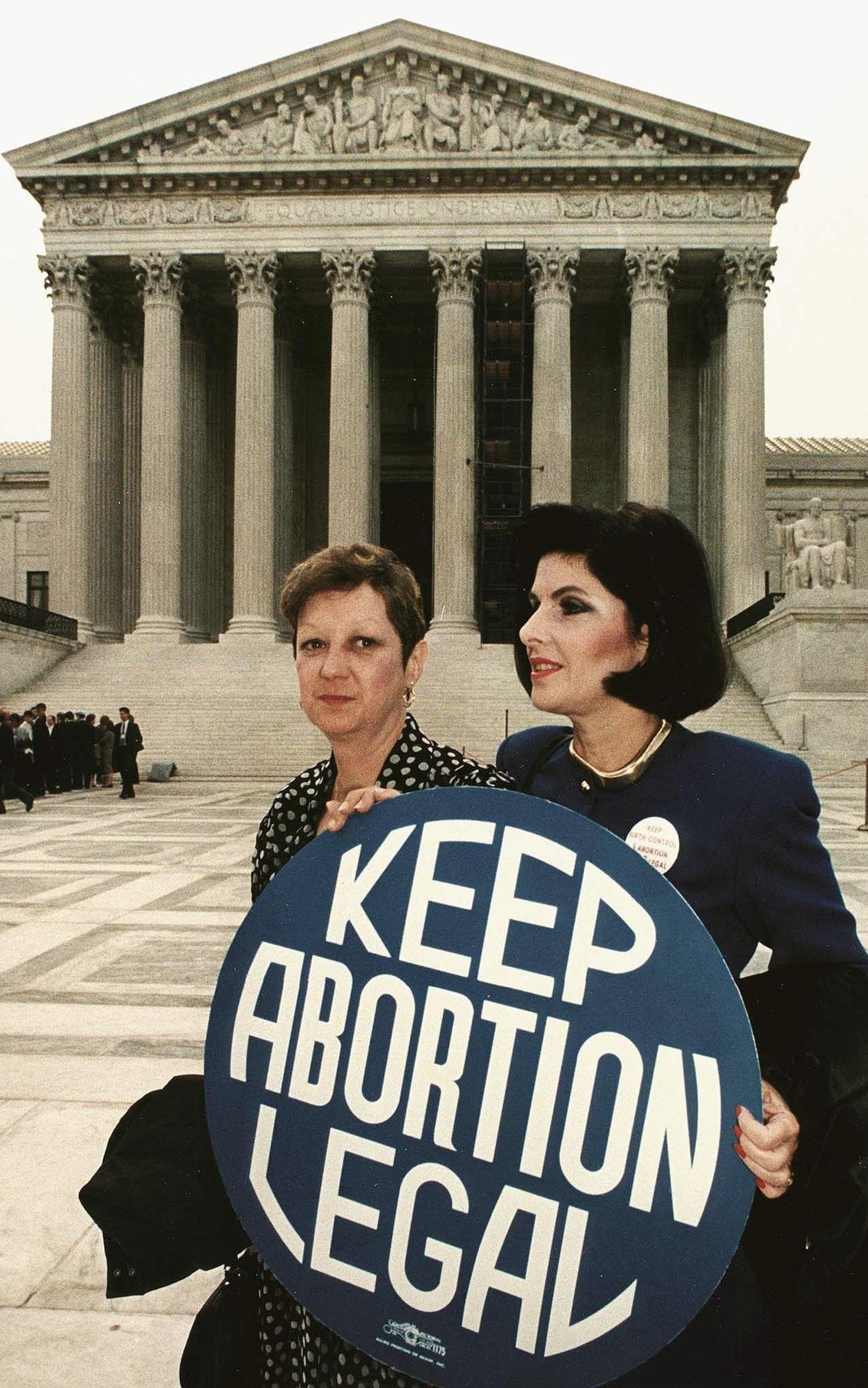

The law that was challenged made it punitive to abort a fetus, whether willingly or forcefully, except to save the pregnant mother’s life. The person challenging it was a young, unmarried pregnant woman using the pseudonym — Jane Roe (real name Norma McCorvey, aged 22); who just wanted a legal abortion “performed by a competent, licensed physician, under safe clinical conditions” when the fetus was not physically harmful to her life.

The law that was challenged made it punitive to abort a fetus, whether willingly or forcefully, except to save the pregnant mother’s life. The person challenging it was a young, unmarried pregnant woman using the pseudonym — Jane Roe (real name Norma McCorvey, aged 22); who just wanted a legal abortion “performed by a competent, licensed physician, under safe clinical conditions” when the fetus was not physically harmful to her life.

In the American scheme of things, the case was a class-action suit, which meant that Jane Roe stood not just for her own cause but for the entire ‘class’ containing all the women in a similar position as hers; and sued Henry Wade, the District Attorney of her place of domicile, Dallas County, to seek redressal of her grievance. The claim of Jane Roe was based on the Right to Personal Privacy guaranteed under various amendments of the US Constitution, which gave her the freedom to choose to do to her body whatever she wanted.

The use of a fictitious name by McCorvey was discussed and accepted by the Court. Most pertinently, the issue of an existing pregnancy to constitute a valid suit was analysed at length. Usually, in US federal cases, the actual controversy should exist at the time of adjudication of the dispute in courts. However, in the present case, McCorvey had already given birth to the baby before this case reached the Supreme Court via the appellate process. Hence the opposite party claimed that the case was now moot as the issue was non-existent.

The Court did not agree with this. It opined — “But when, as here, pregnancy is a significant fact in the litigation, the normal 266-day human gestation period is so short that the pregnancy will come to term before the usual appellate process is complete. If that termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation seldom will survive much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be effectively denied. Our law should not be that rigid. Pregnancy often comes more than once to the same woman, and in the general population, if a man is to survive, it will always be with us. Pregnancy provides a classic justification for a conclusion of nonmootness (sic). It truly could be “capable of repetition, yet evading review.” Two more groups of people — a doctor James Hubert Hallford; and a married couple (with the wife having some sickness but not pregnant at the time of the suit) also wanted to join in in favour of legalising abortion but were denied permission.

The Court dealt with in detail the history of abortion jurisprudence. Starting from ancient history — in the Persian empire, criminal abortions were severely punished. However, the Greeks and Romans performed abortions “without scruple”. In fact, most Greek thinkers like Plato and Aristotle commended abortion. Moreover, ancient religion did not condemn/ bar abortions. A drastic change began with the emergence of religious teachings that were thoroughly and completely against abortions.

the Greeks and Romans performed abortions “without scruple”. In fact, most Greek thinkers like Plato and Aristotle commended abortion. Moreover, ancient religion did not condemn/ bar abortions. A drastic change began with the emergence of religious teachings that were thoroughly and completely against abortions.

Looking from the point of view of laws — the Common law (or that part of English law that is derived from custom and judicial precedent rather than from statutes), around the 16th to 18th century identified the concept of ‘quickening of the fetus’, to differentiate between the criminal levels of abortions.

Quickening refers to the first fetal movements that begin around the end of the first trimester and is thought of as the time of the fetus experiencing the beginning of some consciousness and hence considered by some to be a live human. Abortion before quickening was not thought of as a crime. Whether abortion after quickening was considered a criminal offence or not is still disputed, but the majority opinion is that it was a lesser offence and never considered equivalent to murder.

Then in 1929, England came the Infant Life (Preservation) Act, which emphasised the destruction of “the life of a child capable of being born alive” and made it a criminal offence. However, it made an exception from it when the mother’s life was in danger. The Abortion Act of 1967 expanded the realm of exception to include abortion of a fetus involving “injury to the physical and mental health of the pregnant woman, or any existing children of her family, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated”; and “that there is a substantial risk that if the child were born, it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped”.

It is noteworthy that nowhere in all this debate did the Court discuss the rights of the father, barring a reference to the Roman era.

As far as American legal history is concerned, the Court came to the surprising find that 19th century America was much more liberal regarding abortion as compared to the 20th century. Connecticut was the first state to enact abortion legislation in 1821. Abortion before quickening was made a crime only in 1860. In 1828, New York brought legislation that served as a model for other states.

Although abortion, both before and after quickening, was prohibited, aborting a fetus before quickening was considered a lesser offence. There was also a concept of ‘therapeutic abortion’ which was allowed to save the mother’s life. Gradually in the mid 19th century, the ‘quickening’ distinction began to fade out, and all abortions started to be getting banned, except in a few states.

This analysis of history led the Court to comment — “it is thus apparent that at common law, at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and throughout the major portion of the 19th century, abortion was viewed with less disfavour than under most American statutes currently in effect. Phrasing it another way, a woman enjoyed a substantially broader right to terminate a pregnancy than she does in most States today. At least with respect to the early stage of pregnancy, and very possibly without such a limitation, the opportunity to make this choice was present in this country well into the 19th century. Even later, the law continued for some time to treat less punitively an abortion procured in early pregnancy.”

This analysis of history led the Court to comment — “it is thus apparent that at common law, at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and throughout the major portion of the 19th century, abortion was viewed with less disfavour than under most American statutes currently in effect. Phrasing it another way, a woman enjoyed a substantially broader right to terminate a pregnancy than she does in most States today.”

The Court identified three reasons for the enactment of criminal abortion legislations in the 19th century that also justify their continuance. The first was to discourage illicit sexual conduct in adherence to strict Victorian morals. However, in the present case, the opposite parties categorically denied this as a state purpose in the 20th century. Further, it was realised that earlier abortions were made criminal offences as they involved substantial health risks for the mother. However, modern medical science has made great strides, and abortion now is a relatively safe procedure, especially in the first trimester.

This led the Court to deduce that abortions were banned not so much to protect the unborn child but to protect the health of a pregnant mother. Moreover, the third reason advanced to banning abortions was to preserve prenatal life. It was argued that the state’s interest in protecting a potential life began with the conception of the fetus, and only when the mother’s life is at stake should the potential life be allowed to be sacrificed.

However, the Court acknowledged an abject absence in earlier statutes, legal history, cultural aspects etc., which was that state interest in banning abortions was due to giving protection to the fetus. The Court also delved into the question of the personhood of the fetus. If the fetus is indeed a live person, then they have an inherent Right to Life attached to them, and the mother’s Right to Privacy cannot prevail over it. So, what are the rights of the unborn child and should they be considered a full-fledged person and citizen, garnering equal state protection as the mother?

it was realised that earlier abortions were made criminal offences as they involved substantial health risks for the mother. However, modern medical science has made great strides, and abortion now is a relatively safe procedure, especially in the first trimester.

The Court identified that nowhere in law has the unborn been provided complete legal rights akin to the people who have indeed taken birth. And even the few rights which are given to the unborn are contingent upon them taking birth successfully. There are no easy answers to the issue of ‘life’ of the fetus leading the Court to opine — “We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.” The Court added — “The pregnant woman cannot be isolated in her privacy. She carries an embryo and, later, a fetus,” and “The woman’s privacy is no longer sole, and any right of privacy she possesses must be measured accordingly.”

Also read: What Are Self-managed Abortions?

This leads us to the initial question of the personal privacy to bodily integrity of the mother. Regarding this, the Court held- “This right of privacy….is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” However, the Court did not agree with an absolute right to abortion and recognised legitimate state regulation via-a-vis safeguarding health, maintaining medical standards and protecting potential life. This means that the mother was considered the most important person in a pregnancy, albeit with regulated state interference. It is noteworthy that nowhere in all this debate did the Court discuss the rights of the father, barring a reference to the Roman era.

Finally, considering all relevant observations, the Court came to the creation of a ‘compelling’ time before which the state cannot interfere in the woman’s pregnancy. That time is the first trimester, as it is a widely accepted fact that mortality in abortion during the first trimester is less than that during childbirth. After this ‘compelling’ point, the state may impose reasonable restrictions on the pregnancy to safeguard maternal health, public policy etc.

From the point of view of granting state protection to the potential life of the fetus, the ‘compelling’ point is fetus viability. Viability is the quality of the fetus to be able to stay alive, with or without artificial means, outside of the womb of the mother, which can be considered at about seven months (sometimes even six months) of gestational age. Since, after this point, the state can protect the life of the fetus without the active involvement of the mother, the Court allowed the state to involve itself in protecting the life of the fetus. With this, the Court ruled the total banning of abortions unconstitutional.

Today, instead of acknowledging and progressing over this past law and making laws easier and more friendly for those who can get impregnated, society has been going further into patriarchial orthodoxy and gender repression. Laws need to be amended to extend agency to those who might get pregnant instead of upholding sexist norms which take away the autonomy of women and other marginalised genders.

Also read: Abortion Laws In India: Do Pregnant People Have Agency Over Their Own Bodies?

Medha Pande is a Mechanical Engineer born in Nainital, India. Presently she is a law student and loves writing to satisfy her soul about varying topics and is a published writer in reputed magazines/news outlets like Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), the Wire, the Quint, Hindustan Times and Down To Earth. She has gone to numerous slums for reaching out to people in need of legal aid. Her hobbies include photography, reading, bird-watching, nature walks and watching movies. She is fascinated by the ‘Zero Waste Lifestyle’. She can be found on Facebook.

Featured image source: openDemocracy, Medical News Today