It is not uncommon knowledge that the interwoven intricacies of the media (which is omnipresent, omnipotent and divine in its sheer ability to encompass us) and our internal identities, which is so tiny, and so personal, in comparison that at times, it falls out of our pockets, and we lose sight of it, amongst the bountiful multi-coloured pebbles on the ground.

The romanticisation of problematic activities, like overworking yourself to attain some vague intellectual standard, goes to show how internet subcultures can seed feelings of imperfection in its members. Likewise, the academia aesthetics stemmed largely from 19th century European elite universities, fashion, film & literature—giving way to a modern day, predominately-white, eurocentric, misogynistic and overall non inclusive aesthetic.

For young people, with, arguably, much bigger pocket-holes, the internet is a space to communicate, explore, doom-scroll climate crisis news, and self-identify. The veil of perceived anonymity enables experimentation— whether that be with gender identity, becoming a part of cultures & communities, or aesthetics.

The issue with internet aesthetics is that they are uncannily vague. They’re not really trends—one aesthetic may get popular, but is unlikely to result in everyone subscribing to it. They’re subcultures of-sorts, but have a superficial air of post-modern performativity and only tend to exist online, because their very function, well, their function is largely escapist.

Aesthetics

Over on the internet, we find something new that we like, something that we relate to. We pick it up. We drop it. We find a new one. Our identities are thus dynamic and subject to change by external forces. A socio-political force may magic away the entire rainbow of pebbles from the ground, leaving you with only what you already have and an assigned singular pebble. Or a socio-economic-ecological force may snatch the ground from under your feet.

One such ground-snatching event, the global pandemic, spurred developments in the concept of online communities. For many, people on the internet became friends, through sharing common ideas, interests, or a common “aesthetic”.

Internet manifestations tend to veer towards the problematic, the intense, and the questionable. Let’s analyse 3 globally-popular aesthetics’ cases to better understand this bizarre world.

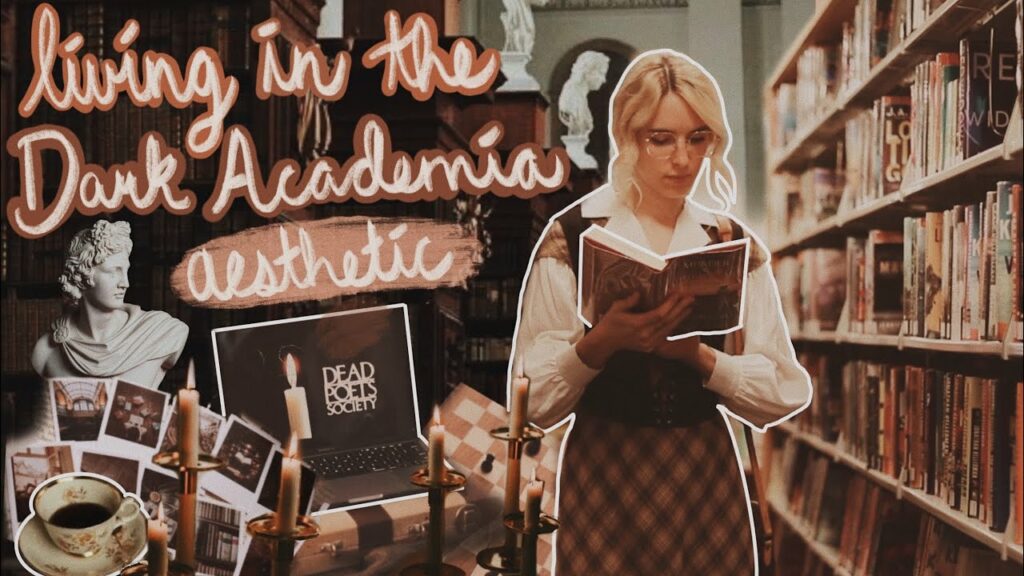

1. The Dark Academia aesthetic romanticises the pursuit for knowledge: it makes studying aesthetic. Naturally, this caught on during the years of online school and university, where students were forced to grapple with studying alone. People started curating a quintessential academic life online, as a substitute for experiences lost, seeking communities of fellow passionate learners.

The Cottagecore aesthetic gained a lot of traction for its soft, light, naturey appeal. It’s all about embracing rural, often agricultural, living, by moving away from the inaccessibility and chaos of urban modernity. Such a subsistence-based, niche way of living has also been interpreted as post-capitalistic by some.

Borne out of a desire to learn, this aesthetic ironically perpetuated a very narrow-minded focus. The romanticisation of problematic activities, like overworking yourself to attain some vague intellectual standard, goes to show how internet subcultures can seed feelings of imperfection in its members.

Likewise, the academia aesthetics stemmed largely from 19th century European elite universities, fashion, film & literature—giving way to a modern day, predominately-white, eurocentric, misogynistic and overall non inclusive aesthetic.

The beauty of internet subcultures, though, is its ability to self-criticise and re-evaluate—giving fruition to nicher aesthetics. Chaotic academia aestheticises imperfections and authenticity—prioritising the actual chaos of studying over superficial colour schemes and trendy outfits. Desi academia seeks to reclaim South Asian cultures, by reading in translation, wearing traditional clothing and drinking way too much masala chai.

Although, it is important to note that Desi Academia, too, is going through the criticism and improvement cycle—namely, because of its predominant oppressor caste-privileged-Indian focus that tends to exclude the diverse intricacies of South Asian heritage. This is not new. A socio-geo-lingual debate over the term ‘desi’ has been going on for a while.

2. The Cottagecore aesthetic gained a lot of traction for its soft, light, naturey appeal. It’s all about embracing rural, often agricultural, living, by moving away from the inaccessibility and chaos of urban modernity. Such a subsistence-based, niche way of living has also been interpreted as post-capitalistic by some. The warm and cheery nature is also quite a fave amongst sapphic communities and queer people in general, because of its ideals of a safe space of its own, that is a progression from real rural regions (which tend to be rampant with homophobia and transphobia).

The problem here is caused by the undercurrent of radical ideologies within the aesthetic, itself. With an idea to reject urbanity, there is an implication of rejecting capitalism. Left-leaning and right-leaning folks both seem to find solace in the aesthetic—albeit for very disparate reasons. For some folk, it is a liberation from patriarchal, heteronormative, ableist, classist cultures, but for others, this marks a reversal back to the good ol’ days of patriarchy (#TradWife).

Aside from the internalised anti-feminism, there is a whole lot more irony to deal with. This is an issue that is not restricted just to CottageCore, but is omnipresent within all aesthetics.

Hint: it’s capitalism.

Despite its seemingly anti-capitalistic notions, a lot of folk who perform the CottageCore aesthetic simply give in to consumerist cultures. Just slap a few strawberries onto an unethically-produced, water-intensive-cotton skirt—fast fashion never knew a better time for greenwashing its problems away.

Cottagecore also has a white problem—it tends to romanticise imperialist european traditions, and is inherently classist. Few have the resources to just up-n-away to the forest, hence the popularity of creating such digital dreams.

Also read: Minorities And Cyberspaces: How Neutral Is Our Internet?

Trying to contextualise this in India also posits several issues. In a country where rural regions tend to be stark, “poor” and fraught with climate disasters, what people deem more important is: opportune cities, economic progression, hustle culture, and “development.” Who cares about public health, ecologies, food security and socio-cultural values anyway?

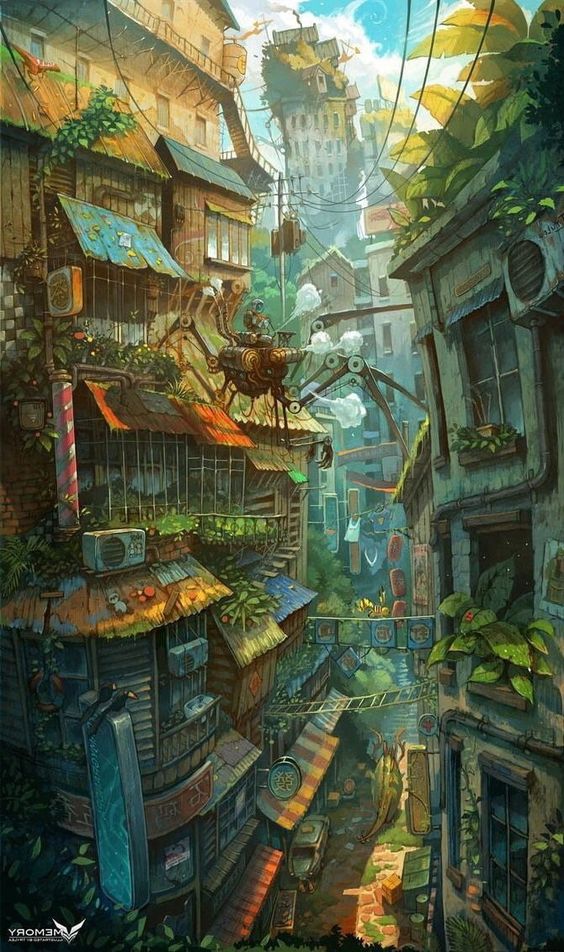

3. SolarPunk: the aesthetic that emerged in response to the apocalypse: a subculture to save the world from crises. But first, some context on punk:

Like most aesthetics, punk emerged from western movements in the 1970s—this one, though, is unique in its political philosophy. According to AestheticsWiki, it emerged as an aesthetic face to pro-anarchist values, with the whole idea being to rebel against the status quo.

While some love the visual fashions in favour of the actual philosophy (as in the case of most aesthetics), most punks do deeply believe the original values—with, even, the lyrics of most punk songs advocating for smashing inequalities. Today, unlike other aesthetics, punk is less popular on social media than it is on videogames, in music, and in film & literature (speculative fiction has its own subgenres for each *insert cool word*-punk.)

While other aesthetics tend to emphasise isolation and solitude, solarpunk nourishes the idea of forming communities even across the expanses of the internet. It’s also gratifying to note that solarpunk takes on a lot of artistic elements from Asian and African cultures, while also prioritising Indigenous land rights, eco-conscious education and holistic climate justice.

The original leather-jacket-and-piercings punk scene birthed various sub-aesthetics: cyberpunk, steampunk, stonepunk, and most recently—solarpunk. Until solarpunk, the futurist punk genre/movement/aesthetic had gotten pretty bleak, dealing with some pretty heavy themes: societal decline, apocalypse, dystopias.

In defiance to climate despair, solarpunk gave people the hope for a liveable, sustainable future. With increasing climate disasters and dwindling faith in governments & corporations to protect our futures, solarpunk offers us the tools to build resilient, ecocentric, inclusive communities. It’s all green plants, cosy dwellings, multigenerational families, and harmonious people.

The main points that stand it apart from cottagecore are its inclusivity and genuinely radical sustainable ideals. That is, except for those designs of tall buildings with plants that are actually quite water-intensive & unsustainable (read: greenwashing); they have since been rejected from the solarpunk canon.

While other aesthetics tend to emphasise isolation and solitude, solarpunk nourishes the idea of forming communities even across the expanses of the internet. It’s also gratifying to note that solarpunk takes on a lot of artistic elements from Asian and African cultures, while also prioritising Indigenous land rights, eco-conscious education and holistic climate justice.

For the first time, here’s nothing eurocentric or homogenous about this emerging aesthetic—we have the creative liberty to contextualise it within our own locally intricate cultures. And most importantly, we can translate this from the internet, to our real lives and designs.

(Digital) Identity (In a Crisis)

The Internet is not the ground. No. The internet is compiled of all the billions of people around you who are dropping and picking up pebbles or who have long dropped and picked up pebbles but whose pebbles are the only things alive about them.

I digress.

The extent to which we manifest our “real” or “public” identities digitally—and vice-versa, needs some thought. We must delve deeper into surface-value digital aesthetics and emerge with societal revolution. We must evolve old aesthetics with newer intersectional values. And we must go beyond the digital realm and take to the streets for true justice.

Trees don’t just grow on the internet. Online aesthetics cannot be simply resigned to a form of escapism, when they are so grounded in our present, real actions. They serve to guide us into a future where we change systems, bottom-up. After all, not everyone has access to the internet, and we need to recognise how this controls knowledge-sharing and marginalisation, even within social movements.

Also read: How Internet Beauty Gurus Sell The Myth of Perfection Online

What aesthetics do you subscribe to? How does it change who you are and how you identify with other people? How can we use this art, these social media platforms, and our digital “self” to further social justice?

And where does that leave our socio-economic-ecologic–public-personal identities?

This is not a Ship-of-Theseus story, this is a question for the digital age.