Trigger Warning: Intimate partner violence and murder

A day after the much-celebrated Valentine’s Day, claimed as a day of love, a murder report surfaced. A 37-year-old woman’s body was found in a bed box in Maharashtra. A few days before that, a report of Nikki Yadav’s murder was headlining. A couple of days ago another murder was reported – a 28-year-old woman died in a fire in Rohini. Last November, Indian television was making the most out of Shraddha Walkar’s murder. These incidents are not scattered instances of violence but are strung together by a commonality – the prime accused is the live-in partner of the dead. The shocking wave of partner homicide is underlined by the status of their relationship. Is live-in relationship the trouble or is the media lopsided in its reports? Are we somehow missing the indicated problem?

Also read: Shraddha Walkar Murder: Is Media Paving The Path For A Theocratic Rashtra?

37-year-old Megha Thorvi was a nurse by profession who shouldered the household costs. Her live-in partner Hardik, son of a diamond merchant and unemployed, was caught fleeing Palgadh, Maharashtra, while Megha’s strangulated body was rotting in the cavity of the bed at their rented house. Reports claim the couple was known to quarrel often. Is that an anomaly in a relationship?

It is important how much information we divulge, how we present it and recon the need for repeating that information. In the name of reporting crime, Indian media has also been finding ways to blame victims and attack the legitimacy of live-in relationships as a domestic unit. When a country’s union minister finds ways to absolve themselves of any responsibility by blaming live-in relationships and drawing out the tired trope of “sanskaar” – it is the responsibility of the media to inquire into the structural violence.

The 28-year-old woman from Rohini was set on fire by her live-in partner Mohit after an argument over drugs. In a horrifying incident, a woman named Sindhu was murdered by her boyfriend Rajesh, who was her live-in partner, in broad daylight. The common symptom continues in this case – clashes in the relationship. It is important to take into account another aspect of the live-in relationship trends in India. Rajesh had abandoned his wife and children to live with Sindhu. The accused in the recent Delhi murder case of Nikki Yadav, Sahil Gehlot was set to get married to someone else. Available information indicates that Nikki was opposed to these plans and was murdered after a confrontation that led to – yes, an argument.

In a debilitatingly gendered list of partner homicide reports, there are some curious anomalies. A woman from Ghaziabad, identified as Priti Sharma, was caught with a trolley bag carrying the dead body of her partner Mohammad Firoz, last year. Claims suggest the reason was Firoz’s refusal to get married after four years of being in the relationship. A third concern that is a common source of discomfort for everyone is the way the bodies are being disposed of. In last year’s infamous murder of Shraddha Walkar, the police and the citizens glued to the news channels were horrified to know that Aaftab Poonawalla had not only murdered her coldly but taken time to discard 35 parts of her body across the city. From trolley bags, bed boxes and refrigerators to spreading the decimated body parts in the depths of a jungle – the homicides reveal a cold-blooded and meticulous design for hiding evidence.

Also read: Victim Blaming, Love Jihad And Islamophobia: Is There A Room For Justice For Women In India?

Yet, is this new? In a quizzical case from Kolkata in 1954, Ujjwal Chakraborty murdered his pregnant partner. He could not balance his dual life as a married man and a live-in partner. Again the question of marriage over a live-in partnership. Again, the discovery of severed body parts at the crime scene. The court sentenced the accused to death. While the patterns seem familiar, the context should not have been. Law Minister Kiren Rijiju recently reiterated that women are protected by The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 in live-in relationships. Yet the government shows no intent to create the necessary framework for live-in relationships. But this brings us to another question – does legality of relationships deter such crimes?

The lack of a legal framework almost always reflects in social behaviours. Murder is illegal, no matter the circumstance. But so is rape, except in the ambit of marriage in India. The number of murders should alarm us about the possible increase in intimate partner violence, reported and unreported. Knowing there is a lack of legal support, survivors of intimate partner violence in live-in relationships or marital rape lack social and legal routes to safety.

The same February that saw the aforementioned carnage was also witness to a petrifying murder committed by a man named Brajesh, in Delhi, of his wife and son. It also witnessed a husband, Nilesh Banduji, murder his wife Jyotsna in Maharashtra over an extramarital affair. Last year Pankaj Maurya, from UP, murdered his wife, Jyoti, justifying it with claims of her interest in staying at someone else’s home for prolonged periods. Again, severed body parts were discovered by the police. But the news that made the most noise last year was Shraddha Walkar – as if we were witnessing intimate partner violence in all its gruesome details for the first time.

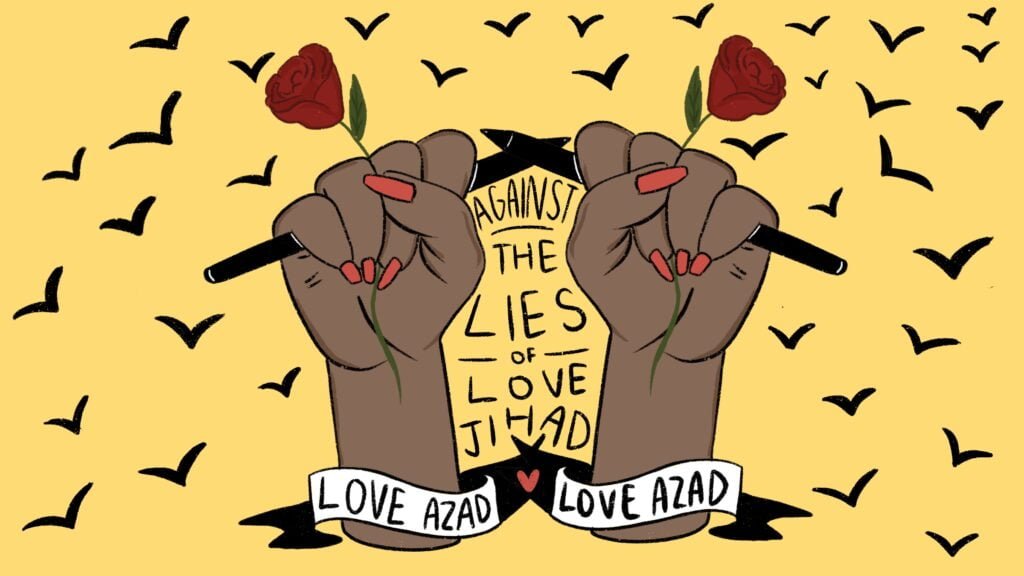

The “unbiased” Indian media in tandem with the mood of our country quickly spun the story of communal hatred – also known as love jihad. Thereafter, cases of Shraddha, Nikki or Megha became stories of astonishing violence. Our audience is well-versed in violent images – trained by cinema and news. As they consume these stories like an episodic tragic drama – they become tools to shame victims and possibly tarnish alternative domesticity outside marriage. Not to mention the possible psychological effect of these violent images and information repeatedly imprinted on their senses. One of the questions arising is, why are so many reports of murders related to live-in relationships?

The National Family Health Survey 2019-21 in India showed that 31.2% of married women in the country have faced domestic violence or sexual violence in their marriages. A 2019 research, published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, indicated that “one in three women in India is likely to have been subjected to intimate partner violence of a physical, emotional, or sexual nature”. It was also noted that only one in ten formally reports physical offence to the police or healthcare professionals. Indian familial laws are largely governed by religious personal laws. The ostensibly religious laws did not initially recognise live-in relationships. Does it now? Not legally. Neither the religious nor the secular laws recognise live-in relationships as a legitimate familial structure. The only statute applicable is the act protecting women against domestic violence.

The lack of a legal framework almost always reflects in social behaviours. Murder is illegal, no matter the circumstance. But so is rape, except in the ambit of marriage in India. The number of murders should alarm us about the possible increase in intimate partner violence, reported and unreported. Knowing there is a lack of legal support, survivors of intimate partner violence in live-in relationship or marital rape lack social and legal routes to safety.

Also read: Shraddha Walkar Murder: A Grave Reflection On Unaddressed Issue Of Intimate Partner Violence

Often women in live-in partnerships have strained relationships with their families. There has been significant evidence that both Nikki Yadav and Shraddha Walkar did not find the necessary support or acceptance from their parents. The National Commission for Women (NCW) urged parents to be more supportive and communicative with their children. A support system is crucial in identifying violence and possibly finding ways towards safety.

It is important that the media recognises its vital role in building sensitive narratives around the recent havoc. The over-sensationalization of murders might even have a detrimental effect on people with compromised mental health. Recent news from UP found a man searching “How to commit a murder” on Google before murdering his wife while Aftaab Poonawala (from Shraddha Walkar’s case) confessed he was inspired by the popular series about a serial killer – Dexter.

It is important how much information we divulge, how we present it and recon the need for repeating that information. In the name of reporting crime, Indian media has also been finding ways to blame victims and attack the legitimacy of live-in relationships as a domestic unit. When a country’s union minister finds ways to absolve themselves of any responsibility by blaming live-in relationships and drawing out the tired trope of “sanskaar” – it is the responsibility of the media to inquire into the structural violence. Gender-based violence, especially intimate partner violence, is not a comfortable conversation. But if we cannot begin that right now, will the blood not be on our hands?

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo