Editorial Note: Being Feminist is a fortnightly column that features personal narratives documenting the emotions, vulnerabilities and innermost contradictions every feminist encounter while trying to push through various degrees of patriarchy in private, professional and public spaces.

I think it is impossible to understate my childhood love for J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter. Between the ages of 12 and 16, I read each book about 20 times. Every social media platform I had access to at the time, including Google Classrooms and other platforms not meant for personal expression, was littered with profile pictures of Luna Lovegood and quotes by Albus Dumbledore. As a teenager, I administered a Harry Potter-themed meme page and posted 4 original memes a day. I was obsessed.

One of the biggest draws of J.K. Rowling’s Potter series for many young women and readers, in general, was how progressive the book seemed. At a time when the fantasy genre was so hopelessly male-dominated, having a book where a third of the core cast was female seemed out of this world. What was more impressive were the themes of poverty and injustice, discrimination and bigotry that the subject matter addressed. The fandom praised the book for addressing real-life issues through its fantastical subject matter.

Personally, I loved the female characters in Rowling’s Harry Potter as a child. In my teenage language, they were badass. Hermione punched Draco in the face. Ginny set a Bat-Bogey hex on her bullies. Luna was weird and had no qualms about it. Hermione, particularly, was always extremely relatable. She was smart, resourceful, and hence always extremely useful to the group.

For a little introverted girl who was only proud of her academic prowess, I related to her like nobody else. Like Hermione, I too wanted to feel included and wanted by friends but also appreciated and needed for my ability to excel in school. If Hermione could have it both ways, I could too.

At the time, Hermione was marketed in the fandom as an alternative to other book heroines. Most prominent of the lot was Bella, of the Twilight fandom. The Twilight vs Harry Potter wars of the early 2010s was rampant, with memes and culture wars afoot. As someone who participated in the Harry Potter fandom at the time, I am not proud to say that I was some part of that culture war. The book’s heroines were a particular sticking point for me and the rest of my peers.

Also Read: An Open Letter To J.K. Rowling On Casting Johnny Depp As Grindelwald

“Hermione was a strong, independent woman who didn’t need a man,” I had written several times. “Bella was a weak girl who relied on a man. Comparisons of the two books also extended to their authors. In those days of fandom culture, J.K. Rowling represented the “modern woman“, the “feminist” woman. She could do no wrong, and Stephanie Meyer was a girly girl, an insult to the movement.

Of course, as a child and young teenager, my critical thinking skills were not great. It took a lot of self-reflection to understand that under a thin veneer of progressiveness, Rowling’s Harry Potter books also purported their own set of sexist and conservative beliefs. It took years of separation from the fandom and a good study of other literature to understand where the flaws in the wildly popular book series lay, and why relating to Hermione as a teenager had impacted me so deeply.

While Hermione, Ginny, and Luna may have been the epitome of female empowerment in my childhood, it takes an analytical eye to see how other female characters are described, and why they are not given the same mantle as these three. Rowling’s authorial voice shudders at the thought of women being distinctly feminine, and all three of these characters are described as apart from this stereotype. They are not obsessed with beauty and vanity, they do not care about their appearance, like pink, or are overly emotional.

Also Read: Harry Potter And The Problem Of Under-Representation Of Women

On the other hand, a character like Fleur Delacour, who is described as both beautiful and vain, but also extremely capable in magic and strength, is derided by our more “practical” female characters for her vanity and her intrusion into their lives. Another instance is Cho Chang, Harry’s first love interest who has an emotional breakdown after the loss of her first boyfriend. A particularly garish scene in the fifth book describes Potter and Chang having a particularly bad date at a “girly” coffee shop, blamed on Chang’s over-emotional behaviour instead of Harry’s lack of sensitivity. Another example is Dolores Umbridge, one of the antagonists of the fifth book, whose major character trait is liking frills, pink, tea, and kittens.

It is easy to handwave away these instances of the derision of female characters because J.K Rowling is careful to give these “feminine” characters objectively bad character traits alongside their femininity.

A 15-year-old me might say that Fleur is hated for her snootiness, not her femininity and that Chang is hated for her petulant nature, not her emotional breakdown. But J.K

Rowling is careful to only associate these overly-feminine traits with characters whom she would like to paint in an unsympathetic light. Characters who are meant to be sympathetic are never assigned these traits, instead characterised as “masculine” in their behaviour: independent and with a penchant for violence against their abilities.

Rowling’s knack for making fun of societal minorities and justifying it by their objectively bad behaviour is not limited to her depiction of women. It extends to her depiction of fat people, other magical creatures (allegories for social minorities), and even activists. Was it really necessary to describe Dudley Dursely as “three times wide as he was tall“, or was it simply justified to do that because he is an objective antagonist? In comparison, “good” fat characters such as Hagrid or Molly Weasley are simply described as “pleasantly plump” or “large“.

Together with understanding the inherent prejudices in the book came an understanding of the biases of the fandom. Recent times have brought around a Twilight “renaissance“, so to speak. While most still agree that Bella had very few defining character traits and her relationship with Edward was remarkably creepy, it is also understood that most of the derision the books and films faced were not out of some objective lack of quality of the text. Neither of the series had literary merit akin to Shakespeare or Dostoyevsky, by any means. The only difference was that the Twilight books and films were mostly enjoyed by a female audience, especially a young female audience, which was the cause of much of its criticism.

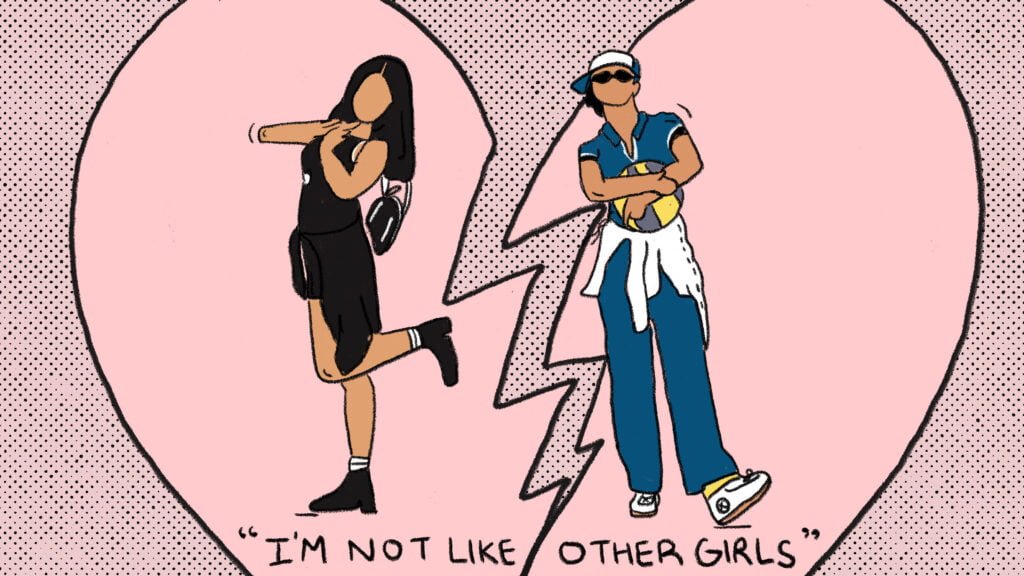

For a young child reading Potter books and participating in fandom, it is easy to internalise these sexist ideas. Unbeknownst to me, alongside practising obscure spells from the books, I was also practising my sense of femininity.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter contributed so significantly to my “not like other girls” phase that I lost many of the interests that I loved in childhood. I didn’t have an answer for anyone who asked me why I stopped putting on makeup or using pinks in my art. I just knew that I wanted to be like Hermione and Ginny, not like Bella and Fleur. I had picked my role models and had lost some sense of myself.

In the years since more light has been shed on J.K. Rowling’s problematic views of gender. Her essays about trans issues and trans rights have rightfully drawn much ire from her fanbase. While some fans wonder how she could have changed so far after her wonderful depictions of women in her books, I don’t.

Also Read: J.K. Rowling’s Exclusion From The Harry Potter Reunion: Justified Or Not?

I know how far I have had to come to unlearn J.K. Rowling’s views of feminism and femininity from my core identity. I remember the palpitations of leaving the house wearing lipstick for the first time and understanding that any bullying I faced for that from other women came from someone who has not undergone the same unlearning process that I had.

I am not a makeup fiend now, but I have a decent collection. I like to use a little eyeliner once in a while. Find the time to put up a few pink picture frames in my room. And that’s okay.