If you are an active social media user or a voracious consumer of news media, irrespective of your interest in technology you must have encountered the buzz surrounding ChatGPT — from the inaccurate answers that it mutters or the imminent fear that it invokes on account of its potential to replace white collar jobs at scale. However, what still remains relatively away from the preview of engagement is how an AI tool, on the surface meant to be a ‘harmless’ instrument to enhance productivity by helping users get directed answers from the myriad of information on the internet, has while proved to be efficient in many ways, it continues to replicate the gendered nature of the world we inhabit.

Take for instance my last interaction with ChatGPT — upon asking it the name of five great historians through the history of humankind; it chose to select a curated list of notable historians including Herodotus, Thucydides, Ibn Khaldun, Edward Gibbon and Fernand Braudel. It was only when asked specifically to answer for female historians, did the system provide names of scholars like Sappho, Anna Comnena etc.

Also Read: IAMAI Report: Digital Gender Divide Lingers In India

ChatGPT’s replication of prevalent gender norms is worrisome not merely because it reinforces skewed gender relations and thereby creates an echo chamber of misinformation in the absence of corrective redirection but also because it is symptomatic of a worrisome emerging trend in the global digital space — one where digital divide threatens to further widen the gender gap globally but more specifically in the developing world.

Digital divide: How is the digital world mirroring gender inequality of the real world

The Covid-19 Pandemic in its wake bought tectonic dislocation in learning and educational outcomes of school-going students. A joint report authored by World Bank, UNICEF and UNESCO in 2021 noted that the present generation of students risks losing $17 trillion in lifetime earnings as against the earlier evaluation of $10 trillion, in present value, or about 14 percent of today’s global GDP.

Learning Poverty refers to the inability to read and understand a simple text by age 10. It serves as a critical indicator of the school system’s functionality or its lack thereof to equip children to acquire not only foundational skills such as elementary learning but is also diagnostic of the school’s inefficiency to help children learn in other areas such as math, science, and the humanities.

In addition, The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery, noted that in low and middle-income countries, children living in learning poverty could reach a staggering 70 percent from the current worrisome figure of 55%. Learning Poverty refers to the inability to read and understand a simple text by age 10. It serves as a critical indicator of the school system’s functionality or its lack thereof to equip children to acquire not only foundational skills such as elementary learning but is also diagnostic of the school’s inefficiency to help children learn in other areas such as math, science, and the humanities.

Closer home, the World Economic Forum underlined that countries like India, which already struggle with low learning outcomes, high school pushout rate and low resilience to shock are at a higher risk of Covid-19 induced short-term and long-term socio-economic dislocations. That India’s digital divide along the rural-urban landscape and its engendered nature is being intensified by existing inequalities is testified by the rigorous data analysis in the wake of the pandemic.

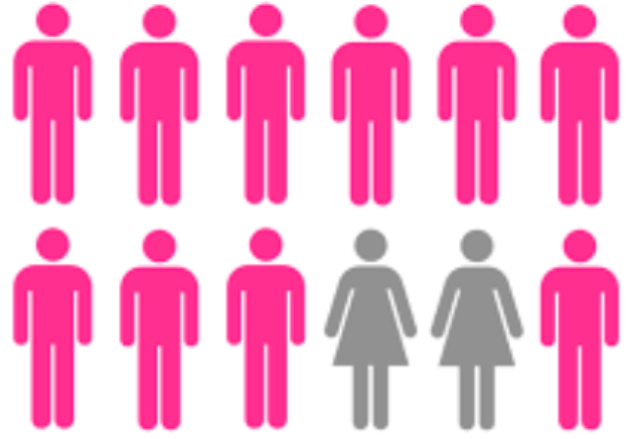

UNICEF’s latest finding on the digital divide’s gender dimension further extends the worrisome findings, confronted first in the wake of the pandemic. It noted that while globally adolescent girls and young women faced significant disparities in accessing the internet, it was particularly stark in low-income countries. Spatially, the data pointed out that the largest gap was observed in South Asia, where adolescent boys and young men were favoured by 27 percentage points over their female counterparts.

A closer analysis reveals that the ability to access remote learning opportunities for students in India was shaped by the fulfilment of operational prerequisites such as stable access to electricity — only 47% of Indian households receive more than 12 hours of electricity according to the 2017-18 survey conducted by the Ministry of Rural Development. Coupled with NSSO data on internet access which underlined that fewer than 15% of rural Indian households and close to 42% of urban households had access to the internet, the picture already looks bleak for India’s vast majority of socially and economically marginalised citizens. What makes this picture starker is that merely 13% of people surveyed (aged above five) in rural areas — just 8.5% of females — could use the internet.

UNICEF’s latest finding on the digital divide’s gender dimension further extends the worrisome findings, confronted first in the wake of the pandemic. It noted that while globally adolescent girls and young women faced significant disparities in accessing the internet, it was particularly stark in low-income countries. Spatially, the data pointed out that the largest gap was observed in South Asia, where adolescent boys and young men were favoured by 27 percentage points over their female counterparts.

While internet access poses the first barrier, the second threat comes from the deficit in digital skills — for every 100 male youth who have digital skills, only 65 female youth do, across 32 countries and territories analyzed in the UNICEF Report. The final barrier is posed by access to smartphones in a given unit of household; across 41 countries and territories analysed, female youth are nearly 13 per cent less likely to own a mobile phone than male youth within the same household, limiting their ability to participate in the digital world.

Also Read: Post-Pandemic Ascend In Gender Divide In Digital India

A personal smartphone coupled with internet access opens the avenue to participate in the rapidly emerging digital ecosystem and thereby gain from the opportunities of the fourth industrial revolution — yet gatekeeping women from accessing the range of opportunities that this period enables not only reinforces the prevalent gender gap but balloons the existing problem of women’s limited labour force participation in India.

Way forward

With generative-AI posing a real risk to the short and long-term labour market by showing the high potential of either automating large chunks of administrative work or driving down wages it is imperative that women are provided with an ecosystem that is necessary to enhance their access to the internet — Internet Saathi, a joint partnership between Google and Tata Trust is an emulation worthy example of corporate-civil society partnership to deepen digital literacy.

While generative-AI may potentially cause massive dislocations in the labour force, it will at the same time create a range of new employment opportunities in the technology sector — a prerequisite to accessing them and being literate in the digital ecosystem. Timely intervention is crucial if one wishes to arrest the gendered digital divide and solve the skewed labour force participation rate that the country is struggling with.

Also Read: E-Education & Access To Information In Lockdown: Digital Divide

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.