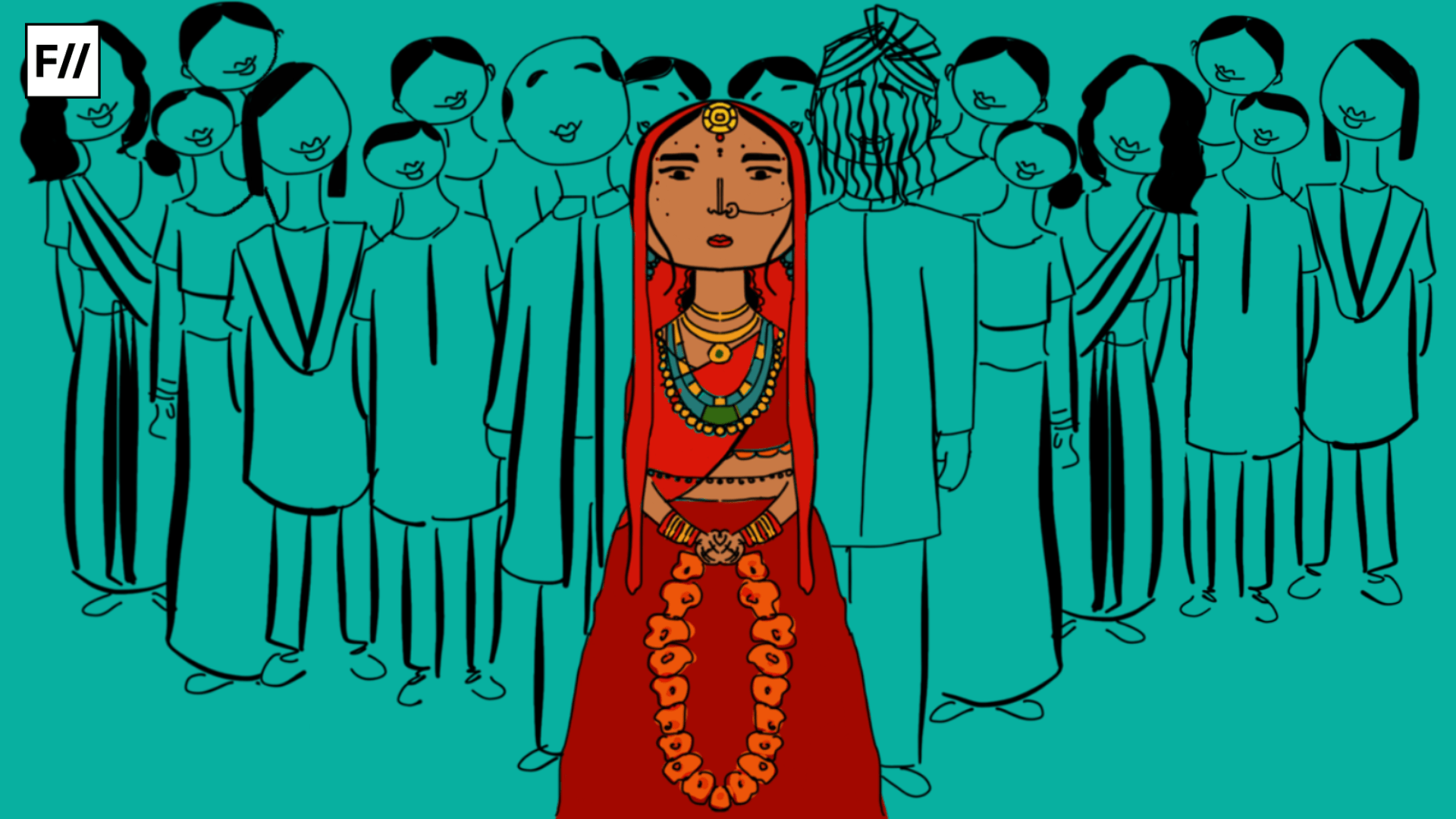

This article challenges the belief that streedhan serves as compensation for women’s lack of inheritance rights. It argues that treating streedhan as a solution perpetuates patriarchal norms, reinforces economic dependency, and ignores the need for structural change. By delving into the social context and debunking flawed arguments, the article emphasises the importance of addressing gender inequality, challenging unequal social structures, and promoting women’s empowerment. The patriarchal compromise that suggests women rely on streedhan as a trade-off further sustains existing inequalities. The article calls for a reevaluation of streedhan, urging society to prioritise equal rights, challenge patriarchal norms, and strive for comprehensive changes that foster gender equality.

Unveiling the illusion of ‘individual choice’ in streedhan

No “streedhan” was ever of the Stree only . These are gifts of patriarchy and not of love.

Unlike today, in the ancient times, immovable assets like land were also included as part of streedhan. However, it is important to note that even in this context, a woman did not have full ownership rights over her streedhan. This is because ancient texts like the Manusmriti propagated the idea that a wife, along with her property, belonged to her husband.

Therefore, the concept of streedhan was intertwined with Brahminical beliefs about women, portraying them as dependent on either their father, husband, or son. Also, the counterpart for men(purushdhan) did not exist because according to Manusmriti, only a woman leaves her paternal home after marriage.

The question of whether the “gifts” given by the bride’s family to the groom are dowry or not come out of only one litmus test. “Svaichcha” i.e. individual choice. Dowry is ‘demanded’ while streedhan is given to “Stree” (woman) by ‘individual choice’ of family members and larger society as it includes gifts given by strangers as well. I argue that both dowry and streedhan are “demands” of a patriarchal society and both make society unequal rather than giving financial support to women.

In assuming that these “gifts” or streedhan are solely made by one’s own individual choice is to argue that one has an isolated individual choice at the first place. A woman might claim a list of items as streedhan but the court does not have to accept all that is being contested by her. The court might accept or reject the demand of streedhan by woman as seen in Pratibha Rani vs. Suraj Kumar case.

A woman might claim a list of items as streedhan but the court does not have to accept all that is being contested by her. The court might accept or reject the demand of streedhan by woman as seen in Pratibha Rani vs. Suraj Kumar case.

Individual choice does not exist as most choices are a product of social conditioning. The is a “social-self” which is not ontologically easily seen but forms a basis for all choices. Privileged individuals who are themselves embedded always in an unequal society (patriarchal and casteist) very often justify the already existing exploitative and unequal social in terms of such “choices”. Example, ‘I am a Savarna and I want to marry a Savarna, not because of underlying caste-system (already existing social-self) but by individual choice.’

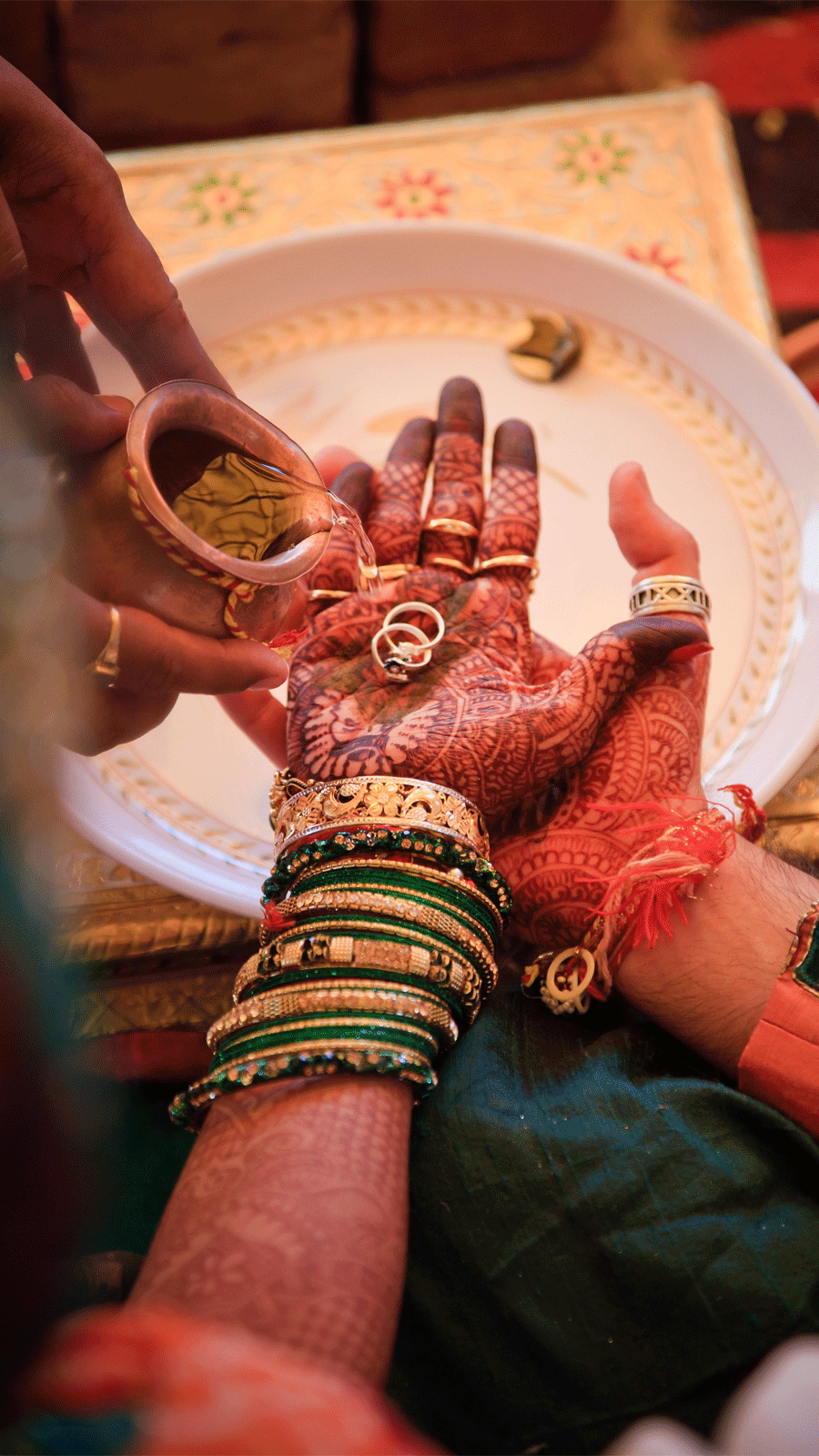

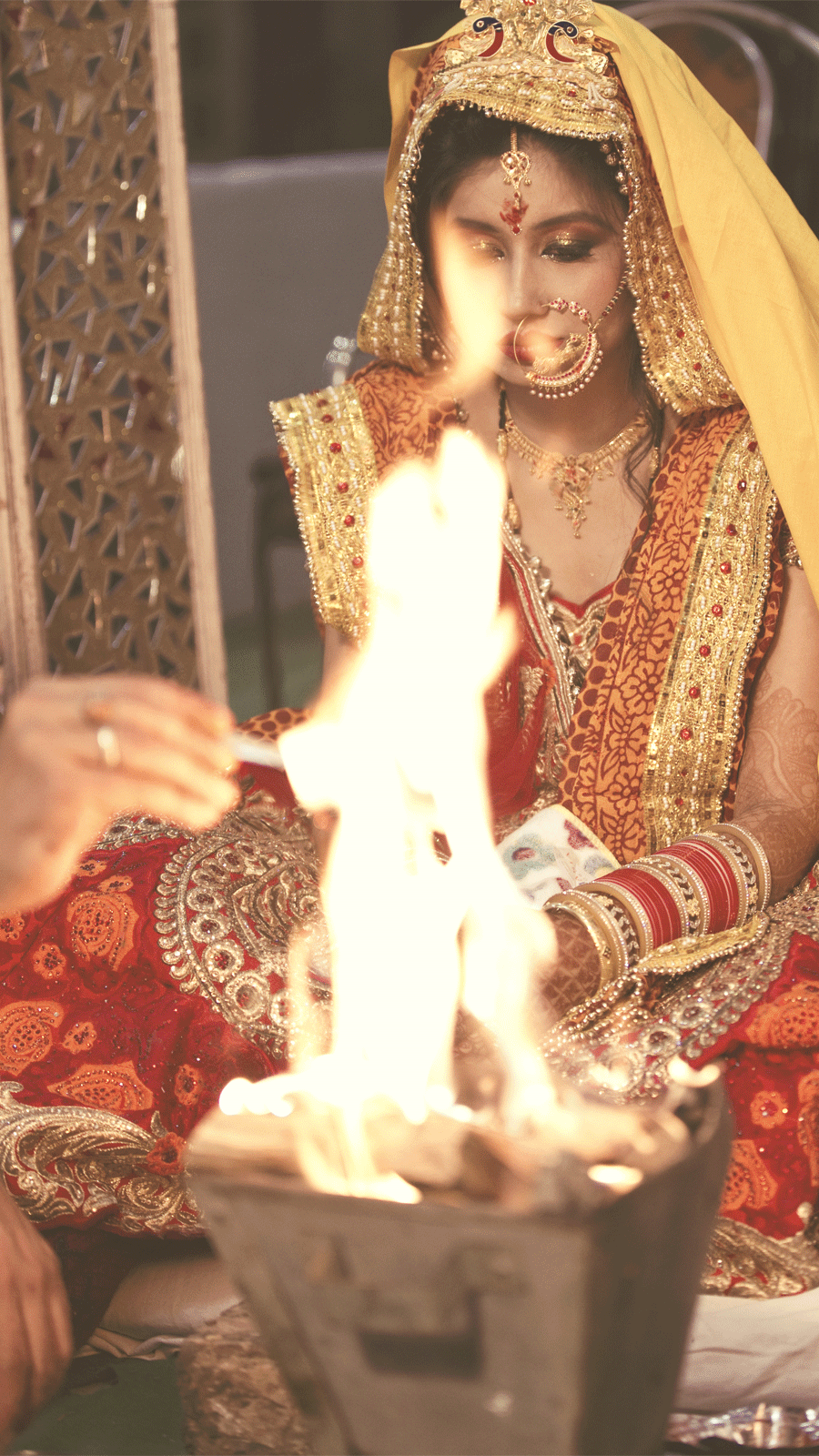

Similarly, one may argue that “gifts” made during marriage to the women are streedhan. Not acknowledging that the ontological existence of streedhan already is a product of an unequal social and thus can’t be called as only an individual choice. Streedhan, that had a different meaning in ancient times, has metamorphosed as a concept with the start of “dowry” demanded by the Rajputs in medieval times. Thus, the demand for dowry (vara Dakshina) gained momentum while streedhan lost its relevance as “woman’s property” by becoming status symbol i.e. matrimonial-gifts. When the british invaded India, the practice of demanding streedhan as a part of dowry was entrenched.5 This led to disturbing consequences such as female infanticide, early marriages of young girls to dying men, and the abhorrent act of bride burning. Despite efforts by Mughal emperors to eradicate the barbaric custom of bride burning, known as sati, it persisted.

Streedhan was divided into two parts: Sauadayika (acquired during maidenhood or widowhood), over which she had full rights of disposal, and the non-sauadayika (acquired as a married woman) for which consent of husband was required.

Streedhan was divided into two parts: Sauadayika (acquired during maidenhood or widowhood), over which she had full rights of disposal, and the non-sauadayika (acquired as a married woman) for which consent of husband was required. Legally, today, the husband has no rights over streedhan but in the realm of social realities, it is a transaction made in the name of woman but enjoyed by the bridegroom and his family.

B. Pramila argues, ‘By giving the right to the wife to have full control over the stridhana, the property in the forms of gifts, presents, jewels etc, the State accorded same legitimacy to the practice of dowry‘. Further, loopholes in the act make it difficult to prove these “gifts” were dowry and not streedhan. Section 2 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, stipulates that gifts presented in the form of cash, jewelry, clothing, or other items are not considered as dowry unless they are given with the intention of being part of the marriage arrangement. This provision appears to undermine the original purpose of the Act. This is because the individuals offering these gifts, typically the bride’s parents and relatives, may not file a complaint in the best interests of the bride. Additionally, it can be challenging to establish that these presents were given as a condition for the marriage.

A fight against such “social-self” which makes the women puppets in the hands of the patriarchal social and not equal partners in marriage, is crucial.

Immovable property vs movable property: prioritising the male heir

It is interesting to note that only “movable” property can be considered as Streedhan. Land inherited from males, was termed as “woman’s estate” under mitakshara and dayabhaga schools. Difference between these two is that woman had limited rights over woman’s estate. However this was done away with The Hindu succession Act 1956 which could not have been possible without the efforts of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar who pointed out the disadvantages in the succession laws for Hindu women and made changes in the existing laws in the new Hindu Code Bill.

Often, in an attempt to justify the practice of dowry, proponents argue that the division of immovable property among sons and daughters is not feasible in India due to the small sise land holdings. They suggest that as a form of compensation, Streedhan can be paid during marriage to alleviate the perceived inequality. However, this reasoning is deeply rooted in patriarchal traditions that inherently favor male heirs over female heirs.

This belief system operates under the assumption that only sons have an inherent claim to property, while daughters are deemed secondary or excluded from this entitlement. In the face of scarcity, where land sizes are insufficient for equal division, the solution proposed by this patriarchal perspective is to allocate the land to male heirs and provide compensation in the form of streedhan to female heirs.

In the face of scarcity, where land sises are insufficient for equal division, the solution proposed by this patriarchal perspective is to allocate the land to male heirs and provide compensation in the form of streedhan to female heirs.

This justification, though presented as a pragmatic solution, perpetuates and reinforces gender based discrimination within inheritance practices where families start pressurising women after marriage for dowry and streedhan becomes only a fictitious metaphor for it. It not only upholds the existing power dynamics that prioritise male lineage but also implies that women should accept their exclusion from immovable property ownership in exchange for monetary or movable property as compensation. This reinforces the idea that women’s economic worth is limited to the gifts they receive during marriage, rather than recognising their inherent rights to equal inheritance.

In this way society effectively perpetuates the cycle of gender-based disparities. Rather than challenging and transforming the patriarchal traditions that underpin this unequal distribution, the focus remains on finding compensatory measures that maintain the status quo.

Reinforcing patriarchal norms: The illusion of streedhan as women’s compensation

Proponents of Dowry often argue, ‘Dowry (demanded as Streedhan) was good (as compensatory way of justice), Patriarchy made it bad.‘ To say so is to argue, that any “consciousness” of inequality of the already existing unequal exploitative social structure, throws dirty water on “compensations” done by the privileged as if they weren’t already intrinsically bad. It is important to ask for rights and not charity, call for revolution and not settlement and to fight against oppression and not compensate for it.

Thus, according to this logic, the caste systen was good as a way of giving reservation (as jobs remained restricted to a caste by birth), but seeing it with an Ambedkarite lens made it bad. It is like saying that the Zamindari system was a good way of giving livelihood to tenants (mostly lower castes devoid of land), but class and caste consciousness made it bad.

Saying that Dowry compensates women for the lack of inheritance rights is a flawed argument because it fails to address the underlying issue of gender inequality and the root causes of the problem that is the structure of the social itself which favors dowry over streedhan.

Legal change and structural transformation

Legally, women today can demand rights of inheritance but in the social realm this is often not easy. The assertion that women don’t seek inheritance and should rely on streedhan or dowry stems from a flawed argument rooted in patriarchy. Many women don’t demand inheritance as a right as a result of already existing stereotypes and social structure which always portrays men as the rightful owners of property. Also, once a girl is married as a child, she usually neither claim a share of her ancestral property, nor such claims, if made, are considered by paternal family as this would involve adding her husband as a new member to the family’s joint property.

Often families justify dowry as compensation for various costs incurred during marriage or as a way of not having to share property and ancestral rights with women. This narrative shows that since society is not ready to accept a social change, dowry or streedhan as forms of trade-off must go on so that it can help sustain the already existing social structure, which is one of inequality.

If streedhan was ever of the “Stree” she could have demanded it. She could have demanded anything that she wants as streedhan, maybe even inheritance in property itself. However, this will never be acceptable to family, in laws or society.

Thus, the if first condition of receiving streedhan would be made to be inheritance in property under the new Succession Act of 2005, and not a trade off to an equal inheritance, many who are vociferous defenders of “streedhan” will start having problems with it.

Definition of Streedhan must be clearly defined in the dowry prohibition act making sure that existing laws around streedhan or dowry become a way of structural social change and not structural social fallacy.

Unfortunately, Systems of shift in power dynamics is not taken well by the privileged, but systems of petty reconciliations are. Legal rights of women over streedhan need to be complemented with addressing loopholes in dowry prohibition act. Definition of Streedhan must be clearly defined in the dowry prohibition act making sure that existing laws around streedhan or dowry become a way of structural social change and not structural social fallacy.

References:

- Halder, Debarati, and K. Jaishankar. “PROPERTY RIGHTS OF HINDU WOMEN: A FEMINIST REVIEW OF SUCCESSION LAWS OF ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND MODERN INDIA.” Journal of Law and Religion 24, no. 2 (2008): 663–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25654333

- Guru, Gopal & Sarukkai, Sundar. (2019). Self and identity, Experience, Caste, and the Everyday Social. Pp 94.

- Pramila, B. “A CRITIQUE ON DOWRY PROHIBITION ACT, 1961.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 76 (2015): 848. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44156653