In many households, particularly in traditional and conservative societies like India, women are responsible for the preparation of food, cooking, and cleaning throughout the day. They serve men, children and elders with platters of food, attend to their needs, and only then eat what is left over. Some women take pride in this and bequeath the same experiences and practices to the next generations due to internalised misogyny and patriarchal conditioning often making them believe that men are superior.

Patriarchal and traditional societies have deeply intertwined customs, norms and gender roles that are rigid. In such societies, culinary and dietary habits and practices intersect with one’s gender, one’s ethnicity, class and caste.

For example, the intersection of food and social class is seen in the prevailing norm that individuals from higher socioeconomic strata consume high-quality organic and superior food, whereas individuals from lower social classes consume lesser-quality food.

So is the case with the caste, the upper caste Brahmins eat ‘pure vegetarian food,’ while the lowered/oppressed castes eat meat and pork, which is considered ‘impure.’ This food politics and prejudice extends to the binary between upper-caste Hindus and Muslims as well. Muslims are considered to be eating impure, barbaric foods containing meat, and poultry.

Food choices and norms are political. Women are often more impacted by food insecurity. In any patriarchal family, as men are given priority to have food first over women who are constantly looking after their dietary tastes and preferences, boys are also given priority to eat better food which results in the food disparity based on gender. The girl child is often neglected and as a consequence, she suffers from various nutritional deficiencies.

Moreover, this prejudiced classification further extends between men and women binary, where women are considered to be eating different foods- the food that women eat is considered to be feminine and the food that men eat is masculine in more or less in Western societies. For instance, look at the famous food phrase, “steak for the gentleman and salad for the lady.”

Forbes writes, “As for you women, how many times have you steered away from the hamburger you quietly craved and opted for the chicken salad, just to seem that little more lady-like? Still, there’s no need to feel sheepish; as it turns out, this gendered reaction to meat is pervasive in Western society, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.”

Food choices and norms are political. Women are often more impacted by food insecurity. In any patriarchal family, as men are given priority to have food first over women who are constantly looking after their dietary tastes and preferences, boys are also given priority to eat better food which results in the food disparity based on gender. The girl child is often neglected and as a consequence, she suffers from various nutritional deficiencies. For instance, milk and other products are often saved and reserved for boys from middle-class families under patriarchal steups. In addition like their elder counterparts, girls look after the family, prepare food, and serve food to the men of the family, while their needs are neglected.

In more rural areas and setups, “daily household chores and maintenance activities such as food preparation and firewood to water collection, women also manage the care work, farming, farm-related activities, etc. That consists of seed selection and preservation, threshing, cleaning and harvesting of crops, maintaining livestock, and planting vegetables in kitchen gardens,” according to a paper called Gender, Water, and Nutrition in India: An Intersectional Perspective. Such gender roles and norms, create food insecurity for women and girl children as they continue to serve and prioritise the needs of the men and attend to house.

Pregnant women and lactating women also suffer this food injustice and insecurity. These women need more nutrition and food security than an average woman or man. However, most of the time, their demands are not met due to poverty, lack of resources and the prejudice that they are lower in status than men. According to ORF, “A 2021 study finding reveals poor dietary intake among pregnant women due to poverty, food unavailability, lack of awareness, food taboos and gender bias.”

It is ironic that apart from food insecurity, dietary practices, dietary habits and in simple terms how women eat the food are also dichotomised. It is perpetrated that women should eat slowly, they should eat less and they should also not open their mouths wide enough to relish a burger. That is considered a masculine trait. Women relishing and eating their bellies full is looked down upon by most patriarchal and misogynistic men and sometimes even women.

Food is political, what you eat, how you consume, where you eat, who you eat with, your taste, your food object of desire, your food security and sustainability, all are political. The policies, economics, and socio-cultural ideas of food are all political and need this gender dynamics and bias based on food should also be seen from the political perspective.

Therefore we at FII, want to know your food for thought and want to create a discourse on the correlation and intersection of the gender dynamics and norms, and dietary habits and practices within our society.

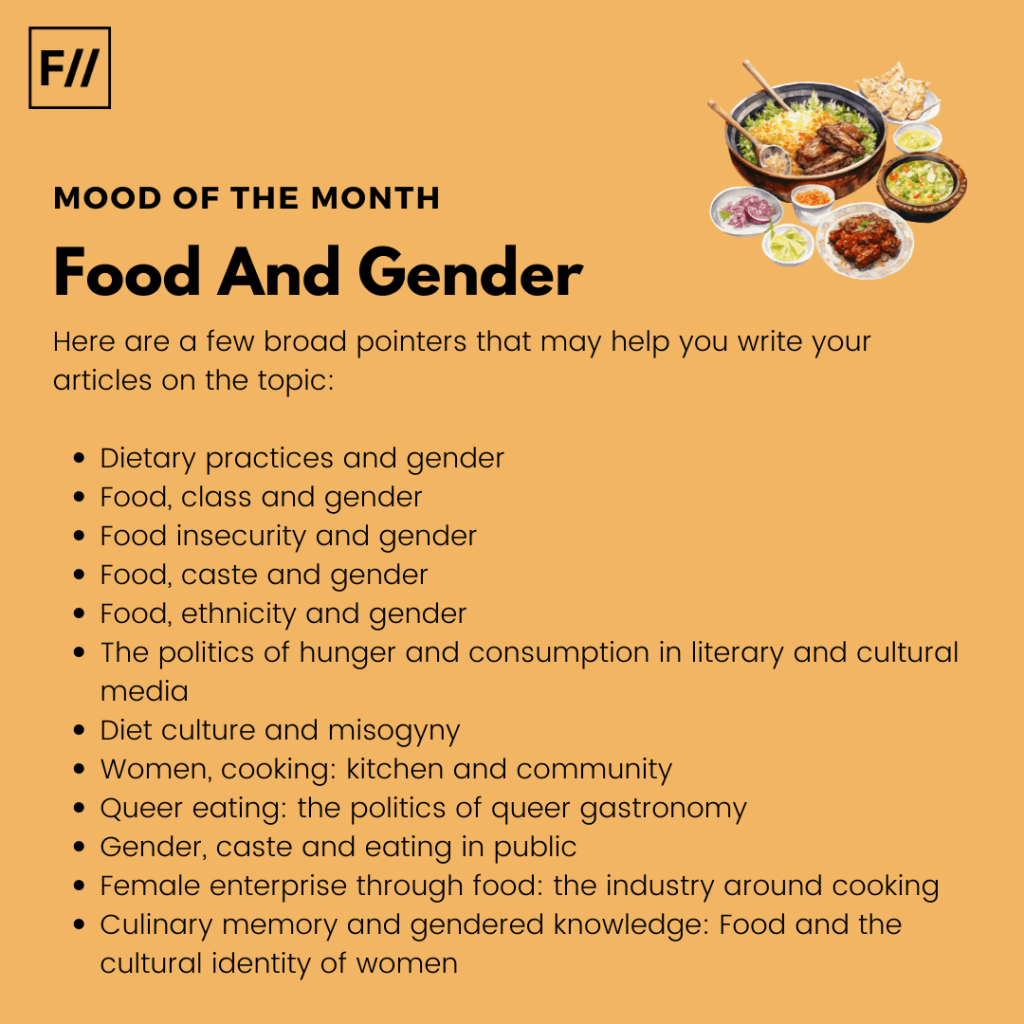

Food for thought: Here are some of the themes that you may find helpful in putting together your thoughts.

- Dietary practices and gender

- Food, class and gender

- Food insecurity and gender

- Food, caste and gender

- Food, ethnicity and gender

- The politics of hunger and consumption in literary and cultural media

- Diet culture and misogyny

- Women, cooking: kitchen and community

- Queer eating: the politics of queer gastronomy

- Gender, caste and eating in public

- Female enterprise through food: the industry around cooking

- Culinary memory and gendered knowledge: Food and the cultural identity of women

- The intersection of nutrition in women, food practices, caste, and gender

- Climate change, food and gender

- Food choices and political discourse in India

- Food disorders, class and gender

- Food and intersectionality

- Food choices at home, patriarchy and women’s role in preserving ‘Indian culture’ through food

This list is not exhaustive and you may feel free to write on topics within the theme that we may have missed out here. Please refer to our submission guidelines before you send us your entries. You may email your submissions to shahinda@feminisminindia.com

Note: Send your entries by 25th of the July.

We look forward to your drafts and hope you enjoy writing them!

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.

Hi! Your submission guidelines require sending a pitch first. Is the same applicable for this call as well?

Thankyou

Hi Garima, yes same submission guidelines apply to Mood of the Month too.

Do you pay for submissions?

Hi there, kindly email for details.

what is the word limit and do we have to send two pitches?

Hi,

Are we required to send in a whole draft by the 25th, or just the pitch?