Parallel Cinema originated in West Bengal in the 1950s as a counter to mainstream Indian cinema. The defining features of films under this movement were scathing social critique, the absence of song sequences popular in the mainstream, and frequent depictions of the lives of the rural and working class. As such, caste discrimination was examined thoroughly: according to Thakur, Moharana, and Bobonga, the first films to address the cruelties under the caste system were Dharmatma (1935), Acchut Kanya (1936), and Sujata (1959).

Later, directors like Shyam Benegal, Girish Kasaravalli, and Pattabhirama Reddy portrayed the intersection of caste, class, and gender in their films. These films played an instrumental role in peeling back the layers of caste hierarchy to reveal its fundamental contradictions. The contributions of these directors to Indian cinema are monumental, and the films they produced have become vital to understanding the history and intersectionality of caste oppression in India.

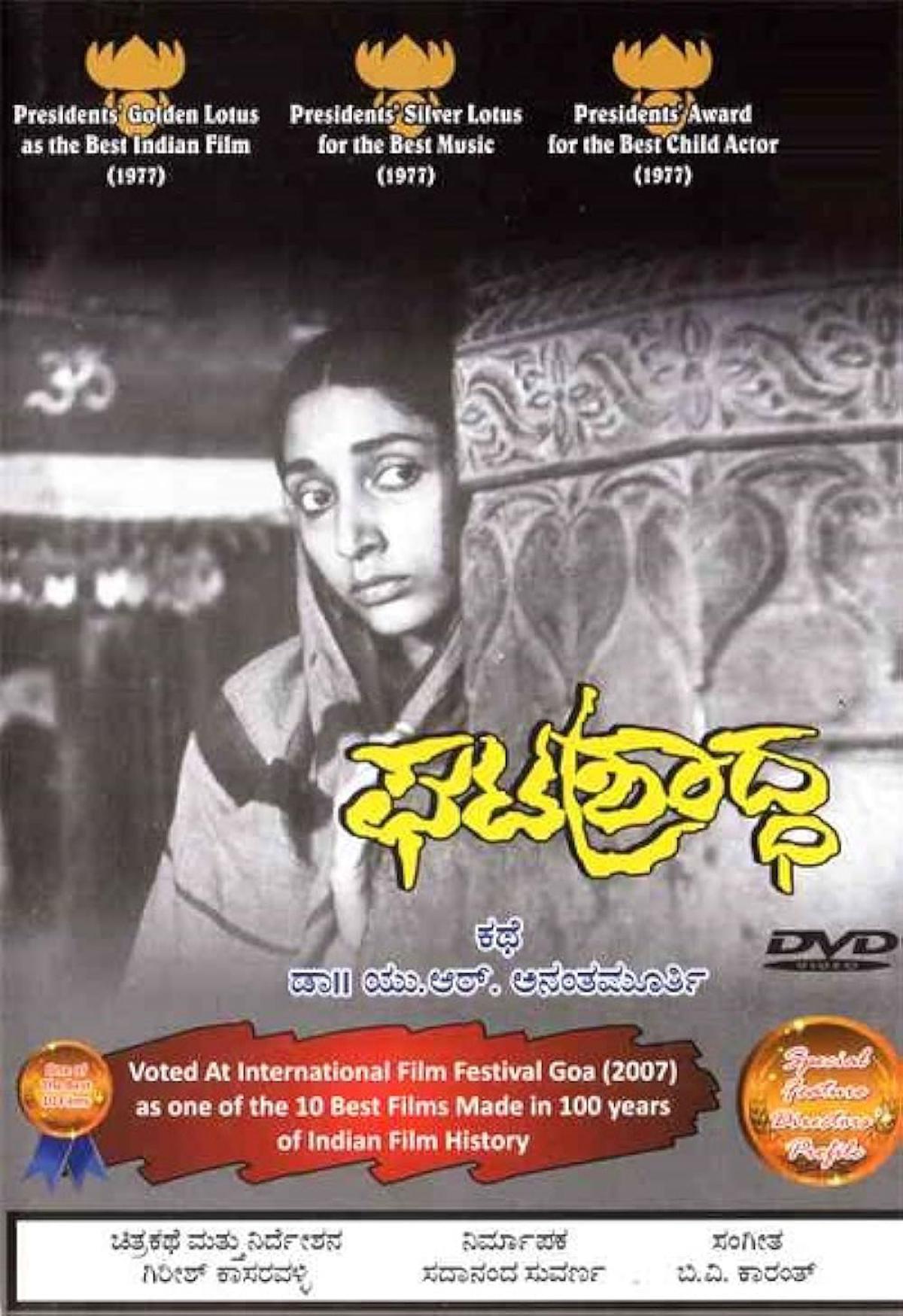

1. Ghatashraddha (1977)

Originally a short story by Dr U.R. Ananthamurthy, the 1977 Kannada film Ghatashraddha or ‘The Ritual,’ is directed by Girish Kasaravalli. The ritual the film refers to is the Brahmin practice of honouring the deceased. A ghata (pot) is filled with water and adorned with flowers – a representative of the family member who passed away. After it is worshipped, the pot is immersed in a body of water or broken.

Typically, this ritual is conducted by a male member of the family. While on the surface this practice seems harmless, the director states that “this ritual of emancipation later on became a ritual of suppression and used by the Brahmin society to excommunicate women who rebelled against a male-dominant society.”

How does this come to pass? The answer is found in the characters of Naani, a young boy bullied by his friends, and Yamunakka, a Brahmin widow and his only friend. The film is set in an orthodox Brahmin village, where Yamuna lives with her father who runs a Vedic school (where Naani is a student). She often meets her lover who is a teacher in the village. The crisis in the film begins when Yamuna is pregnant, and the village comes to know of her pregnancy. It is at the hands of the “voyeuristic” Brahmin boys at the school that the affair is made known to the entire village. She is forced to get an abortion by the teacher and is eventually excommunicated from the village on account of her “immoral” character. In the end, she is isolated under a tree with her head shaved; away from her community and her friendship with Naani.

The ritual in the title comes into play when her father, upon returning to the village from his pilgrimage, learns of this matter. He proceeds to perform a “mock funeral” for his daughter. In essence, she is punished for her immoral and sexual transgression by a strict Brahmin society. Kasaravalli utilises symbols like the pot to represent the destruction of the womb – he aims to depict how Indian society believes it reveres women by assigning moral and religious value to fertility.

In reality, this results in the control, exploitation, and eventual destruction of women’s lives by the upholders of casteist and misogynistic beliefs. Krishna Manavalli elaborates on the misogynistic anxiety entrenched in the Brahmin structure of society that motivates this subjugation. She states that Yamnuakka’s identity is reduced to mere sexualisation at the hands of the men around her, which gives rise to patriarchal anxiety about her sexuality and their desire. Thus, to protect the bounds of society, she is demonised and removed from the village. This, she says, is the fundamental way in which Brahmin patriarchal society defines itself.

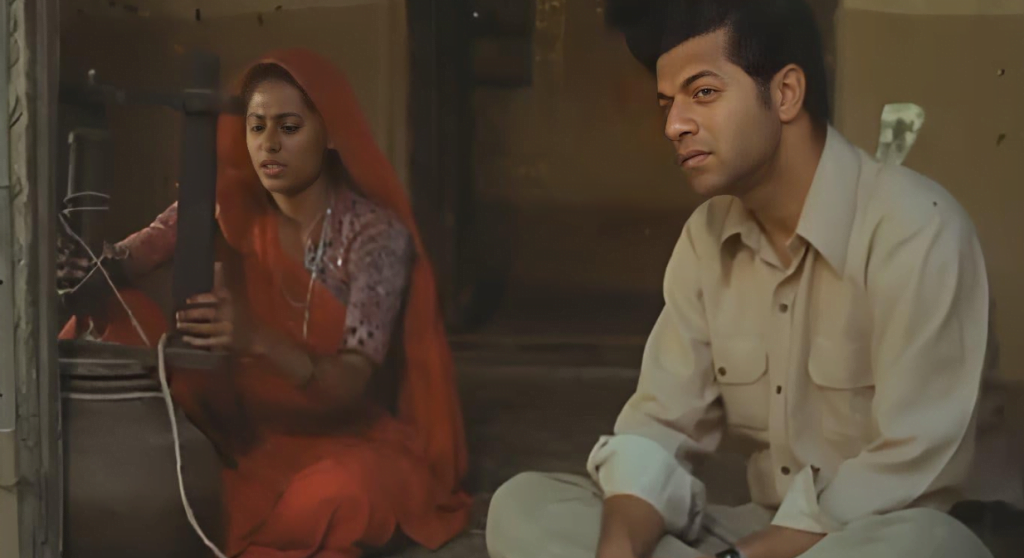

2. Manthan (1976)

Mathan, directed by Shyam Benegal, was released in 1976. It is the first ever fully crowd-funded film in the history of Indian cinema: 500,000 farmers came together for its production. The title means ‘The Churning,’ referring to the process of “violently shaking whole milk which brings its fat globules together, causing them to clump, leading to formation of butter or ghee.” This process mirrors the events of the film – the farmers, initially lacking in unity, change drastically as Dr Rao, a veterinarian, attempts to set up a dairy cooperative in their village.

Inspired by Amul and Dr Verghese Kurien, the film details the difficulties faced in the setting up of this cooperative society for the benefit of farmers. One such difficulty is the lived reality of caste and class discrimination against the Dalit farmers in the village. At the start of the film, Dr Rao points out the system of discrimination set up by Mishraji, a powerful man who buys milk from the farmers at unfair prices. He deprives the farmers of their deserved profits. He then provides them with loans to ‘help,’ them financially. Most farmers are unaware of the exploitation they face at the hands of Mishraji, and the ones who are, are unable to break away from this system due to their indebtedness to him. Thus, he keeps the farmers in the vicious cycle of poverty.

One such farmer is Bhola, a Dalit man in the village. While keenly aware of the discrimination his community faces at the hands of upper caste wealthy men, he is apprehensive about the establishment of the cooperative. His reasoning is sound – what if this initiative too is co-opted by the same men who oppress people like him? An initiative that is meant to redefine the casteist and classist structure of their society might become a mechanism of oppression itself. In an attempt to prevent this, Bhola contests against another man from the upper caste community to become the next head of the village. After many disagreements, Bhola emerges victorious as the Dalit farmers in the village finally unite against their oppressors.

The intersection of gender and caste is thoroughly explored through the characters of Dr Rao and Bindu, another Dalit woman at the forefront of the movement in favour of establishing the cooperative. The two begin an extra-marital affair. After the upper-caste representative loses the election, Bindu is exploited to meet their ends – her husband kills their cow, their only source of income, as revenge for her affair with Dr Rao. Left without anyone to support her, she goes to Mishraji to ask for monetary aid, who, along with the upper caste representative that lost the election, takes advantage of the fact that she is illiterate to make her sign a document accusing Dr Rao of raping her. This is done to excommunicate him from the village. If Dr Rao is no longer in the village, Mishraji can once again exploit the Dalit farmers and deprive them of their profit. Meanwhile, the upper-caste representative will be free to once be the village head.

Other characters that lend themselves to such explorations are Chandavarkar, the man helping out Dr Rao in the village to set up the dairy cooperative, and a Dalit woman from the village. While Chandavarkar leaves the village unscathed after their affair is unveiled, the woman faces the worst of the situation at the hands of her family. She is beaten and then tied up to a pole, preventing her from escaping her “punishment” for overstepping the bounds of caste and gender.

In these ways, the film reveals the intricate relation of upper-caste interests vested in the economic exploitation of lower castes who are also, in this case at least, those from a lower class.

3. Samskara (1970)

Directed by Pattabhirama Reddy, Samskara (Funeral Rites) is a Kannada film set in a village called Durvasapura. Initially banned by the Madras Censor Board, the story revolved around Naranappa, a Brahmin man who was found dead in the village. According to Madhwa customs (the community of Brahmins to which Naranappa belonged), the last rites must be performed at the earliest by the family of the deceased. However, he was a man who broke all the rules laid down by Brahminism: he ate meat, married a “Dasi” (a prostitute) named Chandri and consumed liquor.

Praneshacharya, the ideal Brahmin, is asked to find a way to perform Naranappa’s last rites – Naranappa has no family and none of the villagers want to do so, since they believe he is impure. However, they cannot ask another person who is ‘impure,’ i.e., from a ‘lowered caste‘ like Chandri to cremate his body; after all, he was a Brahmin ‘by birth.’

Praneshacharya, in his quest to find a solution, comes across Chandri. The ideal Brahmin transgresses the bounds of caste and has sexual relations with her – just like Naranappa. Ashamed by his actions, he leaves the village, but not for good. After he leaves, Chandri cremates Naranappa’s body, and as the film comes to a close, the Acharya is seen returning to his village. However, the conclusion is not revealed to the audience. Whether he admits his ‘guilt‘ to the villagers or not is left up to the imagination, calling us to question just how much we trust the integrity of the ‘ideal Brahmin,’ emphasising the fact that morality is unrelated to caste.

Throughout the film, the characters challenge the audience’s perception of rigid meanings of “reality and appearance, tradition and defiance of tradition.” It is through their actions and their contradictory nature that the hypocrisy and moral contradictions in the Brahmin code of law are revealed.

This is by no means an exhaustive or representative list. Suggestions to add to this listicle are welcome in the comments section.

About the author(s)

Aaliya Bukhary (she/her) is student of Economics student based in Mumbai. She is passionate about merging data analysis with her love for writing, and aspires to empower through information. Aaliya also has a fondness for cats and enjoys listening to Mitski!