The famous silver screen of Bollywood has never been big enough to capture the exclusion, discrimination, life and aspirations of the Dalits, Bahujan and Adivasis. Even when Bollywood fell for the remake culture, it failed to remake some of the most outright portrayals of caste in regional cinema like in Fandry and Sairat in Marathi and Karnan and Asuran in Tamil and even when it did a remake in the form of Dhadak, it unapologetically dropped the caste side of the story and sold the story for the consumption of the dominant upper caste Hindus, to not make it commercially enviable.

But the Hindi cinema was not so exclusionary in its initial years. There have been attempts to reflect on the most oppressive system of Indian society which is the caste system in the beginning years of Hindi cinema even though they were not made by the Dalit or Bahujan people but it needs to be talked about.

Era of the 1930s cinema

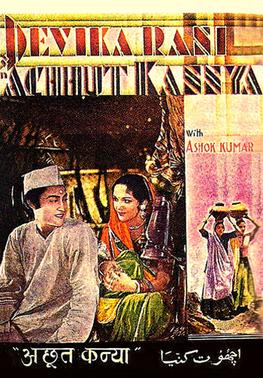

In the 1930s there were a series of films which portrayed caste relations. Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani’s Bombay Talkies produced Achhut Kanya, the love story of a Brahmin boy and an erstwhile untouchable girl. This was the first film based on the backdrop of the caste system. It deals with the protagonist’s inability to cross over their caste boundaries and get married. This film was a landmark in the history of caste conversations in Indian cinema.

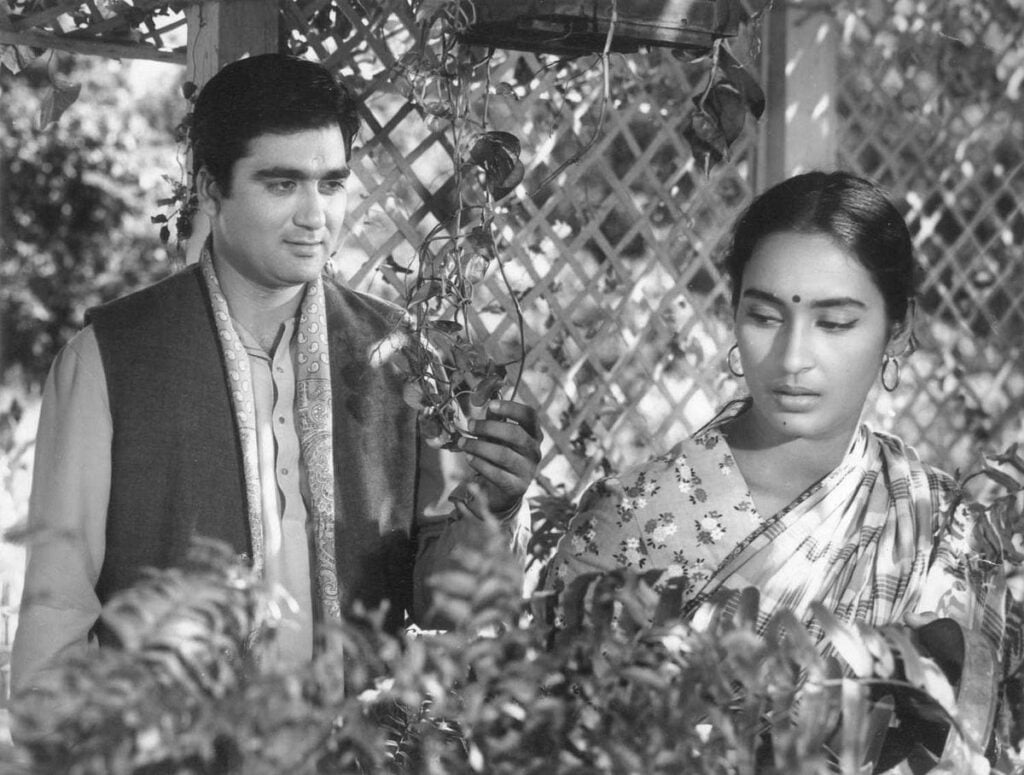

Another film on the same lines was Sujata in which Adheer, a young Brahmin man, and Sujata, an erstwhile untouchable lady, fall in love. It’s also the tale of a mother’s hard emotional struggle to accept her adopted daughter completely.

The film attempts to criticise the practice of untouchability in India by using Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle against it and the Hindu story of Chandalika as its subtext. Although both these films portrayed inter-caste relations, they did not explore the social background of the characters and what causes it in depth.

One can easily notice an upper-caste gaze piercing out of the stories to not disturb the sentiments of the dominant caste of the society, especially post-Independence. “What India’s nationalist movement brought to the forefront was that Indians should be seen as Indians. It wasn’t even recognising that there were backward castes though, internally, the caste system was playing out in society,” says filmmaker Shyam Benegal to Mint.

“Indian cinema came up during this time, so it also reflected the popular feeling. If you look at early Indian films, it is very rare that caste was even a subject in the film. Our films never told you where the hero came from, what kind of a householder d he grew up in, or which caste he belonged to—none of these things is ever seen,” he adds.

This was reflected in the films like Ankur and Kagaz Phool post-independence and Dalit elevated to the form of Nationalist cinema in the 1950s, through films like Mother India. There was another problem, even though Dalit characters found space on screen but there were hardly any people from the community to perform those characters or write those stories. And so those characters were played by the people from the upper castes themselves.

The 1970s is when the Masala genre flooded into Bollywood, with stories and themes that were based on the portrayal of the typical Hero or what they call the “Angry Young Man” of Bollywood took up the burden to free up society from the clutches of oppression, injustice and exploitation. A class conflict was still portrayed on screen but the Caste was nowhere to be mentioned.

Post-liberalisation cinema

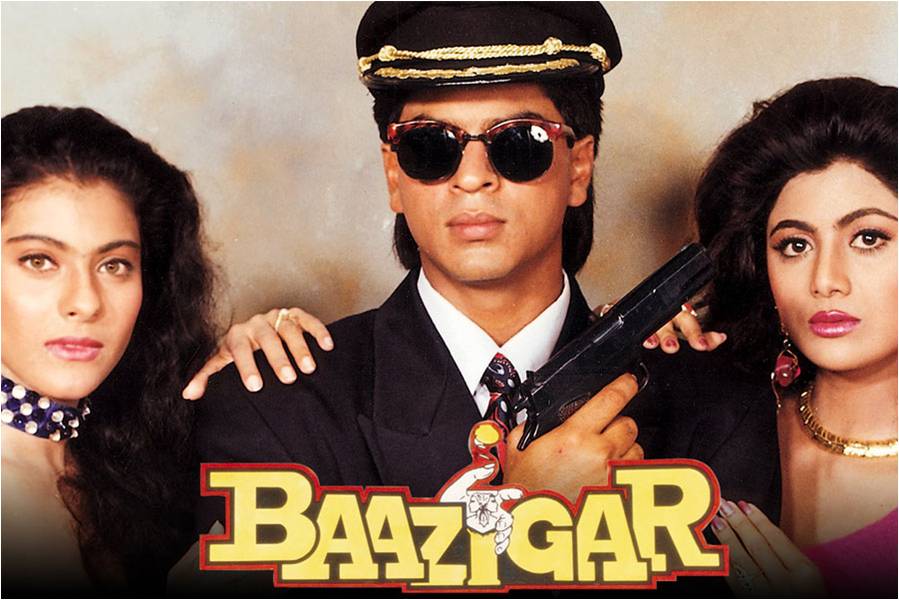

Post-liberalisation cinema is the era in which cinema lost its social reflexivity and then all the themes of larger-than-life love stories, foreign locations, massive sets, and lavish costumes filled up the silver screen expressing the hope of a nation which had just opened up its economy and is beginning to take up its journey towards globalisation, to cater to the imaginations of the diaspora.

Bollywood cinema which otherwise was a collective experience now excluded a large section of society both on caste and class lines, since people from the marginalised sections could hardly afford to pay off the costs associated with the entertainment experience.

The themes of Nationalism got subverted and Caste was cast off. Even love stories did not reflect the dark social realities. The Box Office ruled and cinema as an art form was superimposed with a kind of commercial viability and entertainment question which still has gripped the Bollywood cinema. This became more prominent after the multiplex culture emerged replacing the single screen.

Bollywood cinema which otherwise was a collective experience now excluded a large section of society both on caste and class lines, since people from the marginalised sections could hardly afford to pay off the costs associated with the entertainment experience.

Even though directors like Satyajit Ray who were the pioneers of the ‘Parallel Cinema Movement‘ themes of caste, discrimination and caste violence re-emerged but again depicted the Dalits as broken people in search of a saviour who will emancipate them.

“In this realm, however, even the ‘realistic cinema,’ which is celebrated for its actual narratives and commitment towards presenting a naked truth to the audience, contented mainly in showcasing the superficial populist stereotypes of the marginalised lives and hardly entered into the core debate of social realities,” writes Prof Harish Wankhede.

The era of experiments

In recent times there have been films like Aarakshan and Article 15 which explored the social, political and legal aspects of caste and caste-based violence but both these films reflect the same “Upper caste gaze” as well as the “saviour complex” which gripped Bollywood in the earlier phases.

There have been films like Gangs of Wasseypur or Tumbad which have artistically portrayed caste in a gritty manner but then with films like these the setting is mostly rural which again endorses the stereotypes that caste is a thing of the village and urban spaces are progressive which is not true much to our disappointment.

“In contemporary cinema, it seems that the possibility of experiments has increased; however, its commercial logic still governs the art form,” writes Prof Harish Wankhede.

But then there is a little hope that films like Jhund offer, which have proved caste can be shown in an urban setting, with people from the community playing the characters so that Bollywood does not have to paint the faces of the Upper caste actors browner to portray Dalit characters. Dalit assertion can be portrayed on screen powerfully without stereotypes through the festivals without the angry young man Amitabh Bachchan standing with hands folded in front of the portrait of Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Dalit aspirations can be represented on screen by the people themselves, with no waiting for the saviour and paving their ways out. However, there are not many films like this that too with people from Typical Hindi cinema.

There can always be a balance but the problem of Bollywood is that it has been reflective only of the ideas and cultures of the Upper caste Hindus and any idea of experiment or line of thought that looks harmful to the sentiments of this group will make Bollywood stories fail both critically and commercially.

There are hardly any Dalit actors, writers, directors forget producers in Bollywood and what is astonishing is that it does not even feel a need to address this concern. Even the critics are from the privileged upper castes, who will question the story in terms of technicality or aesthetics but never raise the question of the social responsibilities of the film as an art form.

Hence even in times when regional cinema like Tamil and Marathi has given some great stories portraying caste without stereotypes and have also achieved some commercial success, Bollywood seems to remain under the umbrella which does not want to get itself drenched in the themes of caste or discrimination.

There are hardly any Dalit actors, writers, directors forget producers in Bollywood and what is astonishing is that it does not even feel a need to address this concern. Even the critics are from the privileged upper castes.

That is the only reason that despite there being a strong Dalit movement, led by the Dalits themselves, despite there being so much Dalit literature in place, despite there being so many icons Bollywood could hardly explore these themes and remained exclusionary.

Thus, although Indian cinema never reflected the system of caste oppression on screen it is a classic example of an industry that imitates hierarchies, inequality and denial of occupation which are particularly the traits of the caste system.

About the author(s)

Preeti Patil is a learning enthusiast. She has completed her master's in Politics with a specialisation in International Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She graduated in Electronics Engineering from RTMNU. Her area of interest is Gender studies, feminist security perspectives, Dalit feminism, Caste & diaspora & affirmative action policies.