Since its inception, the theatre has been predominantly male-centric. Through the years, it has embodied various forms, and at each stage reflected contemporary political and societal issues primarily through a masculine perspective. Within this space that reasserts the reality of male power, women’s lives and everyday existences are reduced to supporting roles and flat characterisations. Despite this, many female playwrights have made invaluable contributions to theatre throughout history. Although their work is overlooked or undervalued, they have certainly reshaped the theatrical landscape, challenging conventions and crafting complex, eclectic plays that spurn the male gaze.

Popularly recognised as feminist theatre, these plays, written and directed by women, are driven by a desire to reclaim female voices and agency, challenging patriarchal narratives and power structures. These artists have not only produced exceptional works but also defied conventional theatrical norms. By reimagining plot structures, character development, and even the very essence of theatre itself, they have expanded the boundaries of dramatic art.

Here are seven seminal pieces by women that deserve careful study.

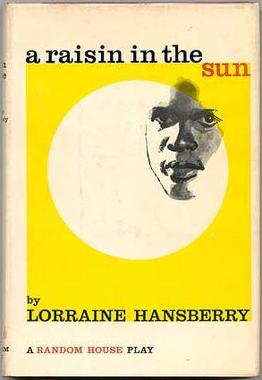

1. A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (1959)

At the heart of A Raisin in the Sun is the struggle of a Black family to find a house in a white neighbourhood. Hansberry masterfully reopens the question Arthur Miller posed about the consequences of the American dream, and applies it to the Youngers family as they attempt to combat the twin evils of racist discrimination and poverty. This is a story that places the home as the site of social security in a state of intense racial turmoil.

Hansberry’s women take up space, make decisions and strive for intellectual and professional independence, even when all odds are pitted against them.

2. Inner Laws by Poile Sengupta (1994)

Poile Sengupta’s amusing comedy Inner Laws tells the story of Lavanya, a newly married woman, who joins the DIL club, an association exclusively for frustrated daughters-in-law. In the format of a mock epic, Sengupta’s satiric exploration of the infamously fraught relationship between the mother-in-law and the daughter-in-law is as thought-provoking as it is hilarious.

Inner Laws’ success, therefore, is in its ability to make the audience laugh through its unreserved social commentary. This comedy chronicles the unlikely transformation of the typically antagonistic relationship of Laavanya and her mother-in-law, while simultaneously offering witty critiques of societal expectations and the quirks that define these women’s lives.

3. How I Learned to Drive by Paula Vogel (1997)

The Pulitzer-winning play concerns itself with heavy themes of sexual harassment, post-trauma, and the protagonist’s journey towards psychological healing. Vogel’s unconventional storytelling technique employs a non-linear structure, allowing L’il Bit to navigate her past in a fragmented and disjointed manner.

Structurally, the play takes on a rather interesting element. The infusion of a classic Greek chorus in the backdrop of a drama that deals with contemporary issues in a thoroughly unconventional, chronological pattern makes for a remarkable dramaturgic experience.

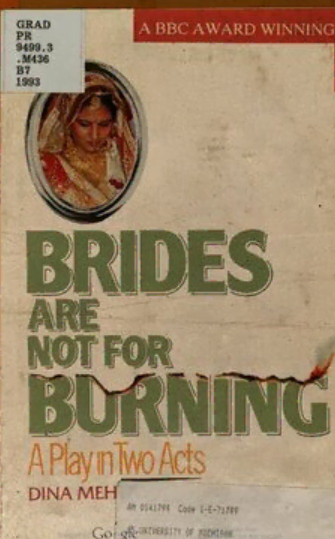

4. Brides are not For Burning by Dina Mehta (1993)

The plot of Brides are not For Burning revolves around Laxmi, a victim of dowry death and Malini, her sister. Malini questions the premise of Laxmi’s untimely demise and concurrently exposes the sustained injustice disseminated by patriarchal hegemony. The failure of the couple to produce children is a weight that must be singularly shouldered by the wife. The play focuses on the oppressive structures of dowry, gender inequality, and the silencing of women, particularly in cases of male infertility or domestic violence.

By examining the performance of gender roles and the prioritisation of male lineage, Mehta highlights the societal pressures and systemic issues plaguing Indian society.

5. Lights Out! by Manjula Padmanabhan (1984)

Manjula Padmanabhan’s Lights Out! is based on an eyewitness account of the physical violence perpetrated on a woman outside the home of Leela and Bhasker. Padmanabhan emphasises the complicity and insensitivity of the aspiring middle class who remain mere spectators even when crimes are committed in their direct sightline. When Leela begs her husband to call the police, he retorts with a “why should we?” This is an uncomfortable story of a dying humanity.

Padmanabhan effectively shakes the audience by the shoulder and asks them to witness the brutality of injustice and the equally great sin of mute spectatorship. As images of the assault haunt Leela to increasingly strong degrees, the viewer questions the indifference of the educated, conscious elite class.

6. Sons Must Die by Uma Parameswaran (1998)

Uma Parameswaran’s Sons Must Die places themes of war, motherhood and loss at its locus. Set against the backdrop of Kashmir’s turbulent terrain, the story follows three women as they grapple with grief upon witnessing bloodshed and political turmoil. The women come from different parts of the country but are united by the maternal anxieties common to them.

Sons Must Die addresses the resounding consequences of war on the common people and asks the question “should sons die?“

The play’s unique configuration immerses its audience in an innovative theatrical experience. The absence of dialogical inter-character interactions, acts, scenes and linear progression adds to the impact of the play.

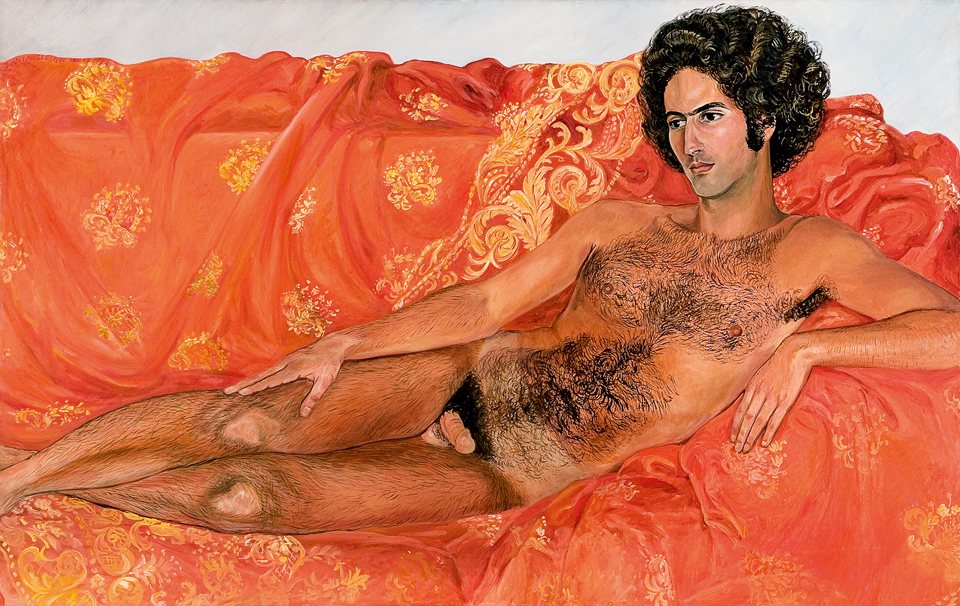

7. In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play) by Sarah Ruhl (2009)

Ruhl’s play In the Next Room is set in the 1880s when the vibrator was first invented to treat hysteria by inducing orgasms. The play explores the failing marriage of Dr Givings, an electrical scientist, and Catherine Givings, his sexually dissatisfied wife. Ruhl additionally inspects themes of ignorance of female sexual desire among women, as well as the complexities of motherhood and breastfeeding.

Dr Givings’ treatment significantly impacts their marriage, as Catherine curiously listens to the happenings in “the next room.” When jealousy invades the household, In the Next Room spirals to its final scenes when Catherine reclaims her sexual agency.

This is by no means an exhaustive or representative list. Suggestions to add to this listicle are welcome in the comments section.

About the author(s)

Gayathri S (she/her) is currently pursuing her master's in English. With a deep-rooted love for literature and writing, she hopes to streamline her interests towards a career in journalism. Alongside her studies, Gayathri has gained practical experience through internships in content writing, editing, and research. These opportunities have strengthened her commitment to impactful storytelling and managing projects aligned with broader social goals. Gayathri looks forward to merging her passion for writing with journalism, where she can explore and report on diverse narratives.