Within urban spaces in India, the stigma around therapy as a mental health tool has seen a notable reduction. The reason why this phenomenon is specific to urban spaces is because of financial and educational privileges which make therapy a more accessible option. However, even as therapy seems to be getting destigmatised, it is important to question if access is equal for everyone.

In India’s current socio-political climate, the instances of violence against individuals of religious marginalisation have significantly increased. In such an environment, the mental health concerns of individuals from these communities proportionately increase. In her piece on the lack of acknowledgement of Islamophobia by India’s mental healthcare systems, therapist Sadaf Vidha mentions that the constant fear of being a target of violence by the police and public, along with constant states of feeling frustration and helplessness at the situation of the community, can increase anxiety. It also increases violence within the community, wherein individuals who are further down the hierarchy in these communities, such as women, children, or individuals from the queer community, and lowered caste communities, face the release of this increased anger fuelled by feelings of helplessness.

An interview with an expressive arts therapist, AB* who works with clients in trauma revealed that when there is always concern and exhaustion about the perception of individuals in the public eye, the experience of any additional trauma is furthered as compared to individuals who are coming from religiously privileged backgrounds in India and facing the same trauma.

In the face of such circumstances, therapists must be aware of the socio-political realities that their potential clients from these communities navigate. The navigation of experiences, even those that are not directly related to their oppression, is coloured by the circumstances of oppression that they face. An interview with an expressive arts therapist, AB* who works with clients in trauma revealed that when there is always concern and exhaustion about the perception of individuals in the public eye, the experience of any additional trauma is furthered as compared to individuals who are coming from religiously privileged backgrounds in India and facing the same trauma.

It is then simply ignorant to believe that mental health and therapy can be kept separate from conversations of religious marginalisation.

The statement above is in no way intended to underestimate the extent of trauma any individual goes through. It is simply to highlight the extent of differences in experiences of the same trauma when they are layered with the intersectionality of religious marginalisation. To further highlight this perspective, a Muslim individual, Sanaf* who is currently in therapy revealed that when they meet someone new their first concerns are, “Does this person perceive me as a threat?” and “Should I be worried that they can threaten me?” It is only when they feel reassured in both these answers that they can proceed to have a conversation safely with people. If one is in a constant state of panic about their basic safety, then any other experiences that they have are being built on the foundations of constant anxiety. An anxiety of being perceived.

The growing agitation against certain religious and caste groups in India (individuals from Muslim, Sikh, Bahujan and Adivasi communities) is not a secret. It is present every day in the myriad of news articles of violence and discrimination. It is present in incidents of increased suicides among individuals from marginalised communities. It is then simply ignorant to believe that mental health and therapy can be kept separate from conversations of religious marginalisation. Mental health can only be accessible to individuals who face marginalisation when they can be reassured that the therapists they reach out to are sensitised in understanding the unique experiences that their marginalisation creates.

Why is there a lack of access to therapy for the religiously marginalised?

When so much research shows that mental health is closely linked to experiences of oppression and religious marginalisation, then why is there still such a dearth of accessibility to therapy for the religiously marginalised in India?

The first and most obvious reason is that religious marginalisation is closely linked to socio-economic marginalisation. Access to therapy is usually only available for those who are financially privileged in India. While some organisations and therapists do offer services at reduced costs or on a sliding scale, they are limited in the extent to which they can sustain themselves. Individuals from communities who are religiously marginalised don’t have access to the same opportunities as those from privileged backgrounds.

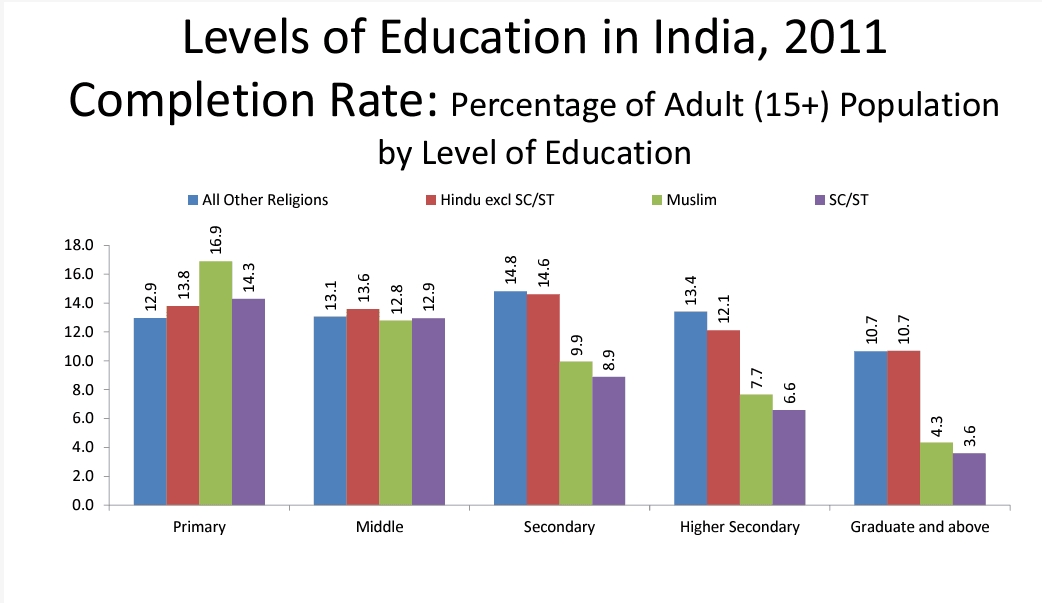

According to the census report in 2011 literacy rates among Indian Muslims were 67.6 per cent and 50.1 per cent for men and women respectively (compared to the national average of 75.3 per cent for males and 53.7 per cent for women). The MCHRDI also found that completion of education across different levels (from primary to graduate levels) drops significantly for individuals from Muslim and SC/ST communities (as shown in the graph below).

Even from the perspective of job opportunities, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2022-23) found that minorities faced a loss of regular wage jobs from the period of 2018-19 to the period of 2022-23. For the Muslim community, it dropped 6.8 per cent points between the two periods, and for the Sikh community, it dropped 2.5 per cent points.

There is a struggle to gain financial upward mobility due to this lack of opportunities. This in turn creates a vicious cycle of therapy access for the marginalised. There is evidence to show that individuals of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to develop mental health concerns owing to their lack of access to basic safety. However, their socio-economic status also does not let them access therapy as a tool to address their mental health concerns.

Nevertheless, this is just one piece of the puzzle. The larger picture is that therapists are simply not trained to identify the importance of socio-political influences in individual experiences. Psychology as a field is taught as if it exists in a vacuum, outside of the realities of socio-political experiences.

An interview with a therapist, A* who has been practicing narrative practice for over a year now revealed that it was important that therapists took a stance on political discourse to make therapy more accessible. Another therapist, Z* mentioned how it was often taught to therapists that they were not supposed to take a stance to be able to be a ‘good therapist.’

Therapists who don’t condemn the violence against the marginalised

In an interview with Adnan*, a Muslim individual who was pursuing therapy, mentioned the relief he felt when he was assigned a Muslim therapist. He claimed that if he had been assigned a non-Muslim therapist, he would have still considered going but he would have constantly worried about how open they would be. The question is, for every person who chooses to continue therapy even when they aren’t certain about identity-based safety, how many individuals stop?

There is also an additional layer to this conundrum. A therapist, X* mentioned that Muslim clients often seek out non-Muslim therapists, especially if their concern is linked to issues within the religious community. However, the choice of individuals is almost equivalent to being stuck between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, they need a therapist who has some distance from the structure of their community, while on the other they are uncertain if they can find a therapist outside of their community who does not perceive them negatively. It is then often easier to abandon the idea of going to therapy and find other means to cope with their concerns.

How can therapy be made more accessible for individuals from religious minorities?

There is no doubt that the decrease in stigma towards therapy and its increased access is primarily only benefiting those who are financially and religiously privileged in India. So, how can therapy be made a more accessible mental health tool?

At the most basic level, the structure of education in psychology has to be brought into question. The idea of psychology being an apolitical field has to be abandoned. Present education of psychology in India is heavily influenced by Western ideas, which centre individuals outside of their identity experiences. There is a need to decolonise conversations of therapy right from the educational level. Therapy training has foundations in medical models which are focused on pathologising experiences and consider them as existing outside of larger systems and structures.

There is also the additional need to sensitise therapists through larger training. Some of this can be through material that is created by therapists already in the field who are from communities that are religiously marginalised. Rather than informing individuals from these communities what they should do, working with mental health professionals who are familiar with the experiences of the community directly is significantly more beneficial. In line with this, it is also extremely important to take mental health work beyond just individual concerns and take on community programs. Working with individuals from the community is the most sustainable way to create more welcoming and safe mental health spaces.

At the end of the day, the empathy that therapists offer cannot be limited to only making individual symptoms of mental health ‘better,” especially when the lens of those symptoms is so heavily pathologised. They have to focus on affirming experiences and systems that are causing these symptoms and hindering healing.

*names have been kept hidden to protect the privacy