Trigger warning: violence, rape

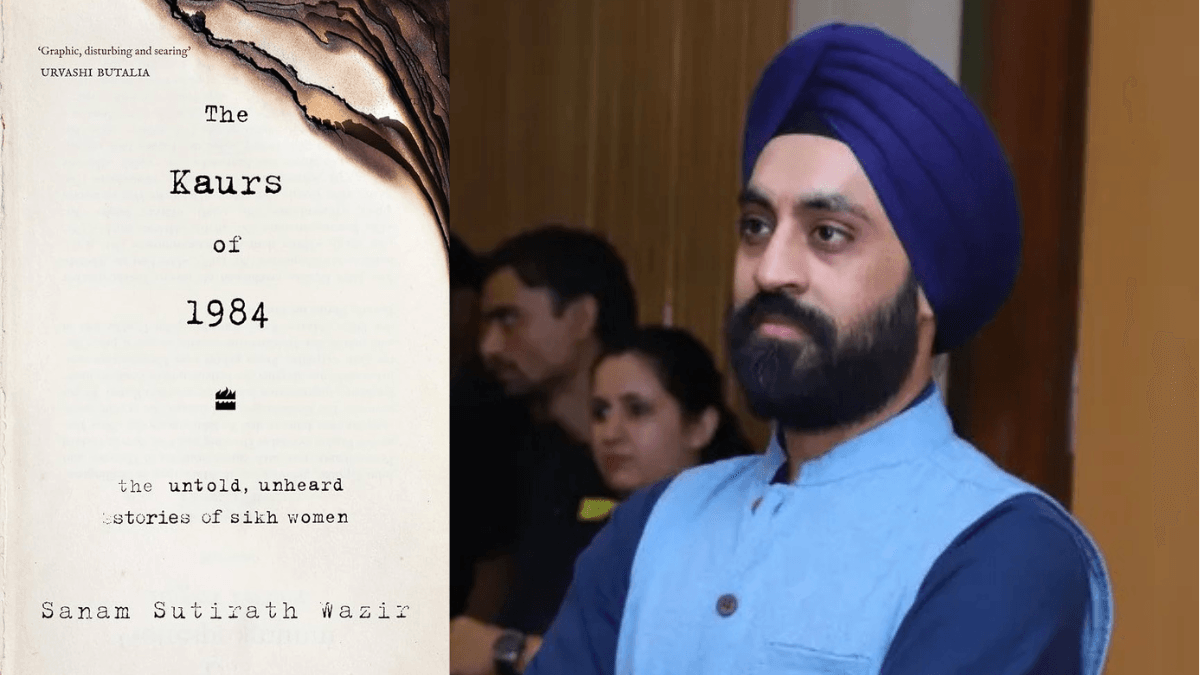

In The Kaurs of 1984: The Untold, Unheard Stories Of Sikh Women published by HarperCollins, the author Sanam Sutirath Wazir documents and presents a repository of chilling oral narratives related by the Sikh women victims of the 1984 genocide of the community. As we are in the 40th year from the genocide of innocent lives in India, it is important to retrospect on the state sanctioned pogrom against the Sikh community in 1984, as we must learn from history lest we repeat it.

As we are in the 40th year from the genocide of innocent lives in India, it is important to retrospect on the state sanctioned pogrom against the Sikh community in 1984, as we must learn from history lest we repeat it.

Amidst rising political tensions between Congress and the Sikh community advocating for more autonomy in Punjab, several militant groups sought refuge with their leader Jarnail Sigh Bhindranwale in Amritsar’s Golden Temple complex. In the summer of 1984, the Indian army launched a sustained attack on the temple grounds to remove Bhindranwale and his followers from the space. The attacks on the sacred grounds, dubbed Operation Blue Star by the government led to huge outrage and fuelled Sikh separatism and militantism.

On 31st October, as the political situation in the nation became more and more volatile, the then Prime Minister and Congress leader Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her bodyguards who were Sikh. This incident led to a series of prolonged and organised pogroms on the Sikh community throughout the nation, leaving behind gruesome murders, plunders and gendered violence in their wake.

Wazir’s The Kaurs of 1984 starts with the haunting days of Operation Blue Star at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. As survivors of the horror recount their experiences of being violently attacked on temple grounds, in a sacred space, the onset of bloodshed is apparent, with the fated events of the genocide to soon follow later that year. Till now, most narratives of the 1984 Anti-Sikh genocide have been about the violence and its gory aftermath, not taking into account how gender comes into play in such situations. Wazir’s The Kaurs of 1984 is groundbreaking, in this regard.

In fact, in 1984, communities in Punjab were still healing from the fresh wounds of the Partition in 1947. Setting up in a newly birthed nation, after witnessing and facing unprecedented trauma, the Sikh community again fell prey to what can only be termed a great betrayal by the State that had promised to protect them. After Indira Gandhi’s assassination, when the religious identity of her bodyguards became reason enough for Hindu men to inflict violence on Sikh men and women, through murder, pillage and rape, the Sikh community in India became victims yet again, this time, of people they had considered to be their own neighbours, friends and countrymen.

Sanam Sutirath Wazir’s text, The Kaurs of 1984 is seminal in the way that Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence was important in the study of gendered history. Maybe, for the first time ever, the gendered violence that erupted during the 1984 pogrom comes to the forefront, through the oral narratives and testimonies of the women who saw it all.

Gendering the 1984 anti-Sikh genocide

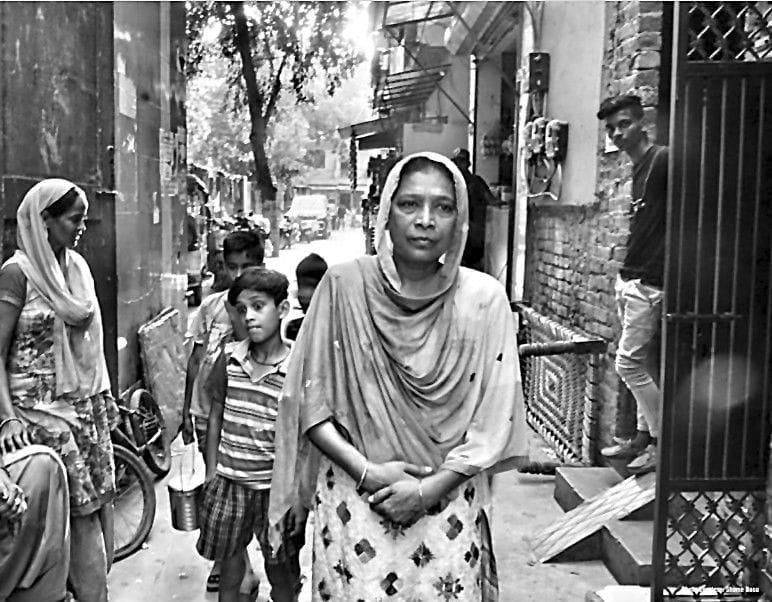

In the section titled ‘Sultanpuri’, Wazir’s narrative takes us to Satwant Kaur, a young wife planning to go to Calcutta to meet her in-laws with her husband. The text relates how excited she was for the trip: ‘It would be Satwant’s first ever trip out of Delhi, and needless to say, she was terribly excited. She had made pickles and had even knitted a new sweater for her brother in law. She had made new sets of clothes for herself as well; she wanted to look her best for this first trip to her in-laws’ home in Calcutta‘.

However, tragedy struck soon. Her and her parents’ homes were set on fire, everything they owned was burned to the ground.

However, tragedy struck soon. Her and her parents’ homes were set on fire, everything they owned was burned to the ground. Satwant was taken to a man’s house where four men took turns raping her. Whenever she protested, she was hit violently. Satwant saw other women being raped around her. All she could think of, she says, was how society would disown her after this and how this was all her fault.

The shame and guilt that Satwant had felt on the night she was raped, were the reasons the gendered nature of the Sikh genocide was not talked about more. Sikh women were afraid of the patriarchal society in coming out with their narratives of gendered violence. Moreover, as Wazir points out, the perpetrators were all Hindu men, like in the Babri Masjid demolition case, 2001 Gujarat riots or the 2020 Delhi pogrom. They were powerful men who, being the majoritarian community in the nation, are rarely held accountable for their actions. Therefore, narratives like Satwant’s go unheard and unacknowledged.

But, as The Kaurs of 1984 tries to do, the accounts of gendered violence during the 1984 pogrom must be told and heard. Wazir’s text shares how there have been few attempts to bring forth justice and provide reparations to the victims. Justice has been indefinitely delayed for long and many victims were even discouraged from seeking it.

In a genocide of this sort, women suffer differently from men as they are already at risk due to the patriarchal social order. In order to subjugate a people, the oppressor wants to conquer the vulnerable body of the community’s women and thereby dehumanise them and the entire oppressed community at large. Therefore, such violence needs to be understood through a gendered lens, which is precisely what Wazir does in The Kaurs of 1984.

The Kaurs of 1984: of militant Sikh women avengers

The image of the insurgent or militant, who has taken up arms for a shared cause, throughout most of history and society, has always been that of a strong man. In Wazir’s The Kaurs of 1984, college students and housewives, daughters and sisters, women who have lost loved ones, faced violence and shared a vision, make up the image of the female Sikh militant.

Most of the Sikh militant women whom Wazir interviewed, took up arms after they had lost close family in the pogrom or to state brutality.

Most of the Sikh militant women whom Wazir interviewed, took up arms after they had lost close family in the pogrom or to state brutality. These daughters and wives of militant men, mostly followers of Bhindranwale, were unyielding and staunch in their beliefs. From Nirpreet Kaur to Jasmeet Kaur, the women militants of 1984 have fought for a cause they believed in and to avenge their loved ones who had been murdered at the hands of the state. They have gone through unspeakable violence at the hands of the police, but they remained firm in their resolve not to give away their comrades:

‘…she was called to sit on a chair which had some wires spiraling around it. It was an instrument of torture, used to give electric shocks to prisoners…

As a consequence of her defiance, she was forced to sit on the notorious chair commonly used for torture in Punjab back in those days…

The first few shocks were painless, so numb was Jasmeet. “I kept praying and asking for strength in order to keep my mouth shut.” A live wire was placed on her hands. She still refused to speak. Finally, they gave her an electric shock in the neck. “That almost killed me, it was so painful,” recalled Jasmeet. But even then I kept my mouth shut. Finally, the officers told me, “O shedanee (crazy woman), make some noise, otherwise the SP himself will come and torture you.” Jasmeet still resisted and, this time, the live wires were placed right on her face. “That was it It. It felt like they’d taken the skin off my face. I screamed and screamed. After that, I went numb.”

However, despite facing such atrocities, none of the militants in their accounts regretted taking up this path.

‘I don’t regret my actions. The government was responsible for alienating young people. We did what was required,‘ said Jasmeet Kaur.

Documentation as reparation for violence

The recounting of oral history is crucial as it begins possibly the first attempt towards reparation for this violence, in a sensitive manner. The Kaurs of 1984 is historical in a time like ours where, in India, and around the world, genocide are being brushed of as “wars” and violence is being trivialised and neglected.

Wazir, in the text, confesses of his hesitancy to take up the project of documenting the genocide through a gendered lens as he feels, as a man he might not do justice to the stories. However, he has done a splendid job of letting the women’s narratives speak for themselves. The narrative is free of an ethnographer’s omnipresence, and Wazir’s writing never takes away from the women’s stories. He is sufficiently detached from the stories, yet is involved in the book just enough. Wazir is passing on the microphone to the Sikh women in the narrative and never does he speak over them.

The text is triggering. In fact, it will shock readers through the traumatic accounts of violence. However, we see, around us, in Palestine, Sudan and India, violence is becoming commonplace. Every day, we wake up to news of hospitals being bombed in Gaza or an innocent Muslim being lynched to death. As we, as a generation living through genocides, continually become more and more desensitised to cruelty, texts like The Kaurs of 1984 jolt us into reality and tell us how devastatingly violent, violence can be, anywhere in the world, at any time in our history.

About the author(s)

Ananya Ray has completed her Masters in English from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. A published poet, intersectional activist and academic author, she has a keen interest in gender, politics and Postcolonialism.

nice experience with this article