A court-ordered survey in the Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh on 24 November led to unrest and communal violence in the area. What followed the survey was a classic example of how Muslims and their lives are treated in post-2014 India. Issues escalate rapidly and end in violence, injuries and killings. These incidents are fully avoidable and can be seen as hate crimes.

The current incident has led to the killing of four men from the area, with two more deaths unconfirmed as of 26 November, detention of at least 15 including women and injury of numerous people. Internet services in the area had been suspended and tensions had forced schools to be shut till 1 December.

What is the issue?

The Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal which comes under the Moradabad division, was constructed by the first Mughal emperor Babur between 1526-1530. It is protected under the Places of Worship Act, of 1991, which states that the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947, must be maintained. A petition claims that the mosque was built on the site of a Hindu temple for the last avatar of Lord Vishnu, Kalki. The site is protected under the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, of 1904 and is a Monument of National importance.

A claim such as the one in the petition would be barred under the Places of Worship Act; however, in similar cases of surveys petitioned for mosques in Gyanvapi and Mathura, the Supreme Court has allowed access to the mosques despite the provisions of the act protecting their religious status. Following the same trend, the District And Sessions Court of Sambhal at Chandausi allowed the survey of the mosque in Sambhal.

Justifying the access to mosques, in May 2022, Justice DY Chandrachud said that although changing the nature of the religious place is barred under the 1991 law, the “ascertainment of a religious character of a place, as a processual instrument, may not necessarily fall foul of the provisions of Sections 3 and 4 (of the Act)…”

Reactions to the survey

Samajwadi Party MP from Sambhal, Ziaur Rehman Barq said reacting to the survey of the Jama Masjid, “Outsiders have attempted to disrupt the communal harmony of the district by filing a petition of this nature in court. The Supreme Court has already stated that, according to the Worship Act of 1991, all religious places that existed in 1947 will remain in their current locations. Jama Masjid in Sambhal is a historic site where Muslims have been offering prayers for several centuries. We have the right to appeal to the high court if we do not receive a satisfactory order from the local court.” Barq has since been booked for provocating the crowd.

Zafar Ali, a prominent lawyer and the Sadar Chief of Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal was detained by the Uttar Pradesh police on Monday evening, immediately after a press conference where he accused senior district officials of orchestrating the firing on Muslim youth during recent protests, Maktoob Media reported. “The mob became uncontrollable because they thought excavation was underway. Despite our appeals for calm and announcements clarifying the situation, the administration’s mishandling and lack of communication worsened the chaos,” Ali added.

Mohammed Sameer, a member of the local aman (peace) committee, said those who indulged in the violence were not from the locality. “These people belonged to nearby localities. There was not a single person in the crowd from the lane leading to the mosque. I tried to reason with them to maintain peace, but I was also struck by a stone,” he said in a report by the Indian Express.

Academician Apoorvanand said, “Courts have now made it so easy for anyone to demand that his curiosity be satisfied by ordering survey of mosques. Dr Chandrachud opened the flood gate but that does not mean the top court should not stand up and make 1991 Places of Worship Act effective.”

The question is then raised about the protection of Muslim properties anywhere in the country – when the courts can defy constitutional provisions that are meant to prevent such instances of unrest, where do the disharmony and violence end? Properties have been under attack since the previous term of the current regime with the popularisation of the bulldozer. Muslim majority neighbourhoods in Tughlakabad and Jahangirpuri, Delhi saw the demolition of homes and shops with little to no prior notice last year. The CM of Uttar Pradesh has indulged in self-proclaimed “bulldozer justice.”

Sambhal in crisis and what led to it?

What’s specifically interesting here is how rapidly the events progressed. The timeline of filing the petition to its move to action was not just fast but also followed a smooth process.

The petition was instantly heard and acted upon, an advocate commissioner was appointed for the survey within hours and the two rounds of survey were undertaken within a week – an initial one on 19 November and another on 24 November which sparked protests. These are the same courts that let guilty sexual harassers run free and the same government that praises them and even allows them to contest in elections.

The Moradabad riots of 1980, the Meerut riots of 1987 and the Delhi riots of 2020 in Northeast Delhi as well as the unrest in Delhi over the controversial CAA-NRC acts are just some of the major examples of the pattern over the years.

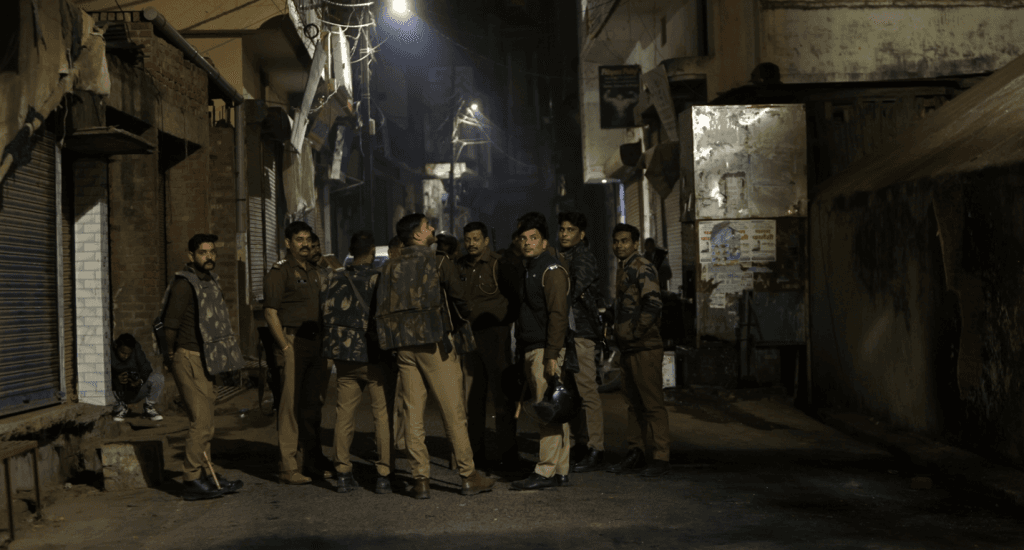

Soon after the survey in Sambhal, the blueprint of communal violence took charge – stone pelting by a mob, tear gas and lathi charges by the police forces and detention of civilians along with sloganeering and incitement of violence. It must be noted that this series of events has become increasingly common with violence and riots happening multiple times a year. The Moradabad riots of 1980, the Meerut riots of 1987 and the Delhi riots of 2020 in Northeast Delhi as well as the unrest in Delhi over the controversial CAA-NRC acts are just some of the major examples of the pattern over the years.

Consequences of the Sambhal violence

The irony in the timing of the violence in Sambhal is its proximity to the Constitution Day which is celebrated on 26 November every year marking the completion and enactment of the Indian constitution. The Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution would never have envisioned a day when the minorities of the country would live as second-class citizens. With each passing incident, Muslims in India become exceedingly worried for their future. The communalism follows the backdrop of the Babri Masjid demolition of 1992 the ripple effects of which can still be felt in the community. The fear, anxiety and apprehension still exist and they are only getting worse.

The extravagant inauguration of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya earlier this year was a spectacle for the nation and added to the uneasiness of Muslims across the country. The innumerable orange flags that still stand tall in support are a political statement upholding not just the Ram Mandir but the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the riots that followed, decades prior.

Incidents are not limited to rioting or sloganeering, microaggressions and taunts are a reality for Muslims every day and violence just adds a new layer to the discomfort of being an Indian Muslim. With minimal to no Muslim representation in the Parliament and unsafe spaces in elections, now the judiciary cannot be trusted either. Trust in law and order crumbles when the police forces are seen and reported to be open-firing on civilians.

SP Bishnoi of the area made a statement warning dissenters of further protests and said, “We are following a zero-tolerance policy towards criminals. Those arrested will face the Goonda Act and the National Security Act.” It seems to be a trend that constitutional provisions lose meaning when petitions arise in court and the same constitution is used to threaten dissenters in a democracy, more specifically using draconian laws like the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and National Security Act which have been misused on numerous occasions and are known to be stringent and discriminatory.

About the author(s)

Sara Siddiqui is a freelance journalist from Delhi. Her passion for writing and the need for social justice drew her to journalism. She believes words can change the world. Sara has bylines in the Indian Express and the Millennium Post as well as published work online. She posts her original poems, book reviews, and personal essays on her WordPress blog.