With the third wave of feminism in the 1980s, there was a substantial shift in the kind of scholarship being produced in Women and Gender Studies in the west as well as in the countries of the global south. It was during this period that, influenced by poststructuralism, feminist theorists began to question the centrality of hegemonic structures.

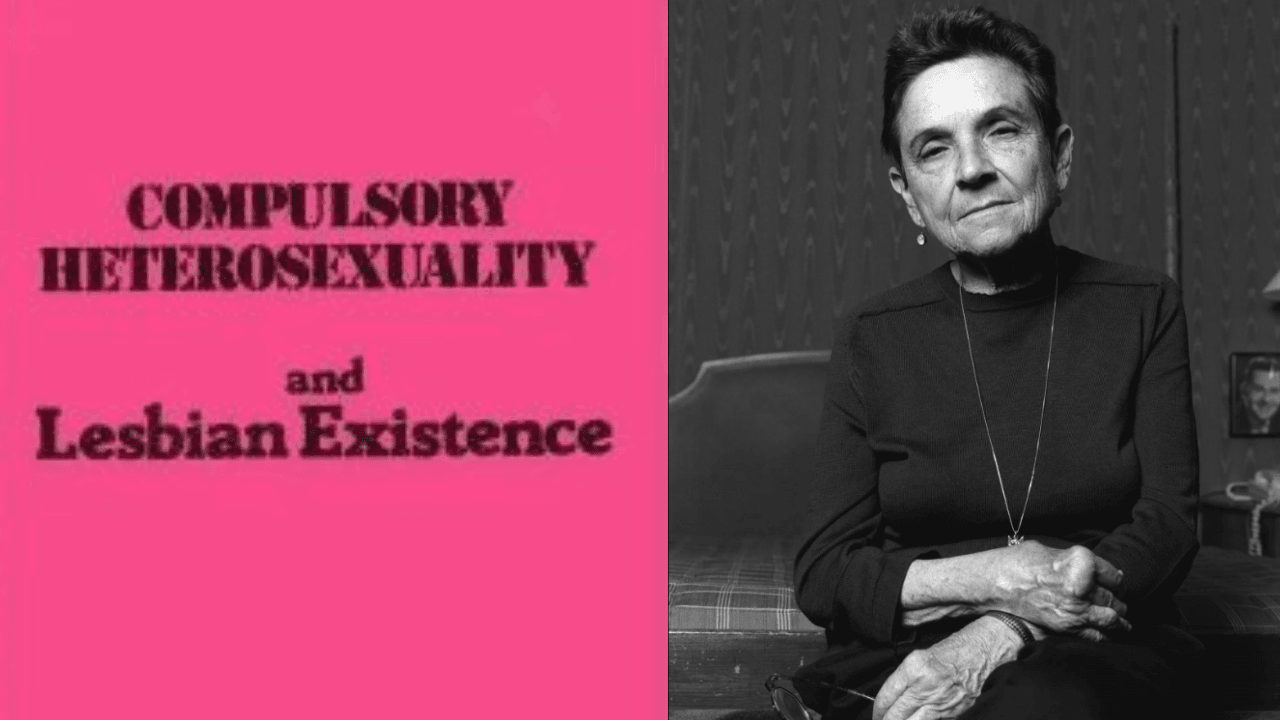

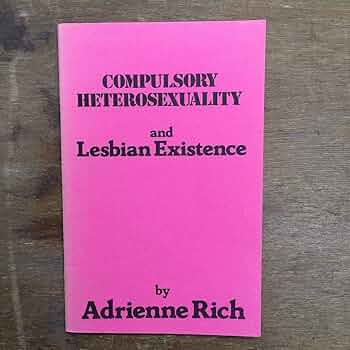

Adrienne Rich’s Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, which was published in 1980, is a foundation text in the discourse of destabilisation of gender and the inception of queer theory in the third wave of feminism. This foundation text premises its argument by stating that the normative discourse of hetrosexuality was based on the erasure of lesbian existence. Rich is questioning theory, including that of the feminist scholarship preceding her. She opines that hetrosexuality, in its ambit, assimilates “those who can manage it—is the most passive and debilitating of responses to political repression, economic insecurity, and a renewed open season on difference.”

In this ambit, lesbian existence is reduced to a deviation or just an asexual preference that must remain closeted. She continues to critique the medicalisation of women’s bodies and identities through “various cures, therapies, and normative judgements in different periods.” Her critique continues to target the emergence of psychology, which pathologised queer identities through “treatment.” For Rich, rather than a focus on the history of human sciences in light of the collaboration of social contracts between men and women, feminist scholarship should build on those identities that were historically ostracised.

She writes, “witches, femmes seules, marriage registers, spinsters, autonomous widows, and/or lesbians—have managed on varying levels not to collaborate. It is this history, precisely, from which feminists have so much to learn and on which there is overall such blanketing silence.”

Lesbian existence and lesbian continuum

Rather accentuating on lesbianism, Rich introduces the term “lesbian existence,” which is also a political assertion that connects queer identities across temporality. Close to this terminology, Rich also refers to the notion of “lesbian continuum” in her essay, which highlights a feminist comradeship amongst women that is emotionally knitted. She is offering a critique of masculine power relations by problematising the enforced “emotional, erotic loyalty, and subservience to men.” She cites Kathleen Gough’s “The Origin of Family,” explaining how coercion and violence are central to the maintenance of asymmetrical power relations between men and women.

Rich is questioning various forms of subordination that are based on biological determinism. Nividita Menon, in a similar argument, puts forth in “Seeing Like a Feminist,” “If ‘normal’ behaviour were so natural, it would not require such a vast network of controls to keep in place….Why would we need laws to maintain something that is natural?“

Dissecting the fetishised image of women in pornography and popular media, Rich is revealing the voyeuristic gaze of these media. She writes that these advertisements “depict women as objects of sexual appetite devoid of emotional contexts, without individual meaning or personality.” She also puts forth the relationship between capitalism and heterosexuality and how these masculine structures feed each other. In the radical argument, she writes about the possibility that “men fear that…women could be indifferent to them…that men could be allowed sexual, emotional, and economic access to them only on women’s terms.” Concluding, she writes that feminist discourse must move ahead of western women’s studies. Rich asserts to move from the personal to the political through resistance. This resistance is against models of power, which is also the model of exploitation and illegitimate control.

Gender, a social construct

Judith Butler highlighted in Gender Trouble (1990) that gender and the compartmentalised category of ‘woman‘ are socially, economically, and culturally contoured. Hence, a universalised category of “women” ignores the modification by their intersection with “racial, class, ethnic, sexual, and regional modalities.” For instance, in The Colour Purple, in the background of the Jim Crow era, the marginalised status of Sophia before Miss Millie, the mayor’s wife, remains evident on the premise of race.

Joan Scott writes in “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” “We need a refusal of the fixed and permanent quality of the binary opposition, a genuine historicisation and deconstruction of the terms of sexual difference.” “Gender is a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes” is one of Scott’s many definitions of gender. “Gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power,” the speaker continues. Because society rejects or suppresses alternatives, some gender stereotypes endure.

Individuals behave “as if these normative positions were the product of social consensus rather than of conflict,” assuming that the dominant narrative is the only one. She cites fundamentalist religious organisations as an example of organisations that seek to put women back in the “traditional” role. In the light of the text The Colour Purple, the alternative is a same-sex relationship between Shug and Celie along with a consolidated Black community that emerges as a negation to the “American Dream,” which is a fetish of the white bourgeois household. The issue here, Scott observes, is that there may be a faction that works to bring old binary definitions back in reaction to societal change. She advocates for a continual and constant questioning of how gender is incorporated into the structure of people’s lives. Isolation on the basis of gender binary is a cultural phenomenon, according to Scott. However, resistance and dissent need to be on a continuum for her.

Building on the feminist legacy of Rich, Butler and Scott are both perhaps arguing to mould the epistemology around gender to “trouble” to create counter-discourses and indulge in a freeplay with the centrality of the binary.

Thus, the lesbian continuum persists with a diverse array of resistance theories and literature that critiques any form of identity that is enforced.

References:

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge, 1990.

- Nivedita Menon. Seeing like a Feminist. Zubaan Penguin Books, 2012.

- Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 15, no. 3, 1980, pp. 11–48.

- Scott, Joan W. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” The American Historical Review, vol. 91, no. 5, Dec. 1986, pp. 1053–75, https://doi.org/10.2307/1864376.

- Walker, Alice. The Colour Purple. Pay Per View, 1982.

About the author(s)

Anchal is a writer, poet and spoken word artist based in New Delhi. Her works have been published on various platforms, including Enroute Indian History Blogs, Indian Review E-Journal and department and annual magazines of Miranda House, Kirori Mal College and Gargi College. Currently, she is pursuing an MA in English at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and loitering around the city.