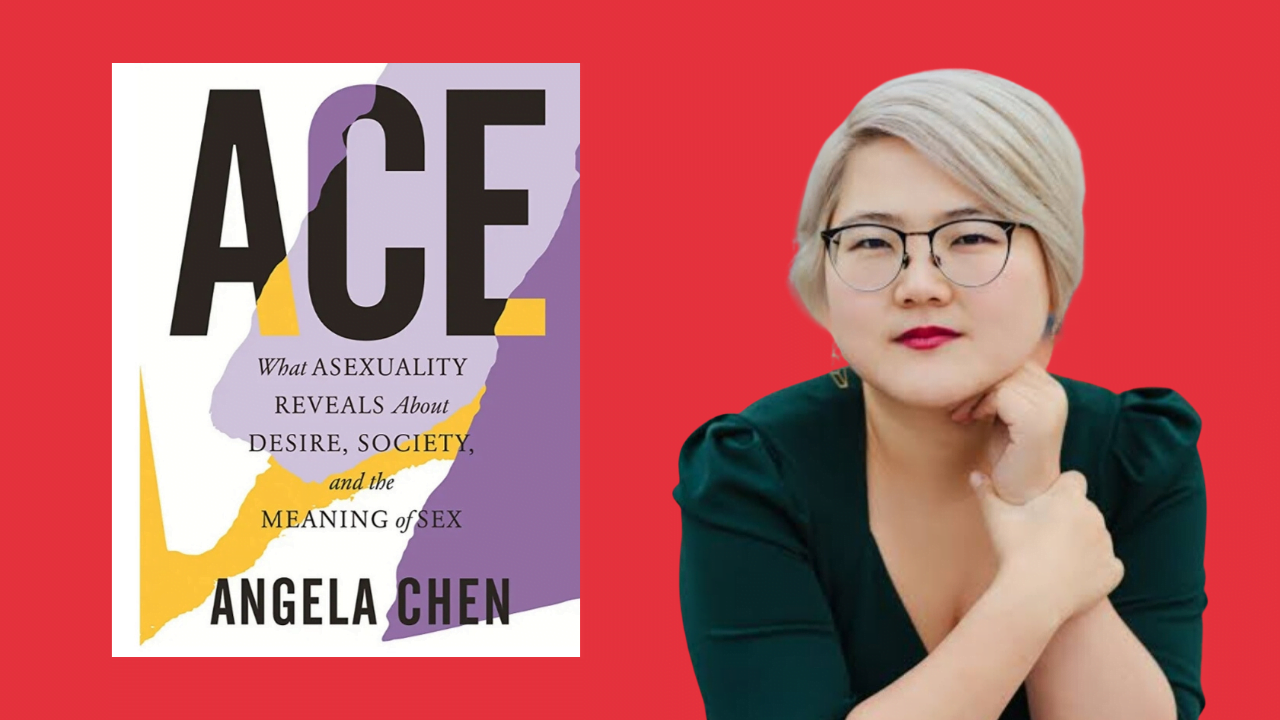

Discussions surrounding sexual orientation and gender identities have gained momentum in India and across the world. However, asexuality remains an overlooked and misunderstood subject. The discourse surrounding asexuality has grown recently, challenging our fundamental assumptions about human sexuality. Angela Chen’s groundbreaking book, Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex, serves as an insightful guide for understanding this issue.

Published in 2020, it was the first book of its kind, combining research, anecdotes and cultural analysis to draw a comprehensive picture of asexuality and its impact. Chen invites readers to explore the diverse aspects of asexuality and achieve an encompassing understanding of human sexuality. She asks us to reflect on how we think of sexuality and challenge our preconceived notions. Whether you identify as asexual or allosexual, reading Ace is an enlightening experience.

Published in 2020, it was the first book of its kind, combining research, anecdotes and cultural analysis to draw a comprehensive picture of asexuality and its impact. Chen invites readers to explore the diverse aspects of asexuality and achieve an encompassing understanding of human sexuality. She asks us to reflect on how we think of sexuality and challenge our preconceived notions. Whether you identify as asexual or allosexual, reading Ace is an enlightening experience.

This review examines key concepts and poignant quotes from Ace, putting forth a picture of asexuality while dispelling the misconceptions associated with it. It also delves into the impact of asexuality and asexual discourse on individuals and society at large.

Exploring asexuality: Understanding a diverse spectrum of human sexuality

So, who are asexuals? What is asexuality? There are no simple answers to these questions. Asexuality is often defined as “the lack of sexual attraction to others”. This understanding implies sexual attraction to be normally present in humans, and defines asexuals by their lack of this phenomenon, as opposed to allosexuals, the “normal” people who experience sexual attraction. In a chapter titled Explanation Via Negativa, Chen discusses the same. “It requires us to use the language of “lack,” claiming we are legitimate in spite of being deficient, while struggling to explain exactly what it is we don’t get,” writes Chen.

Additionally, this also comes up with quite a narrow understanding of asexuality. Asexuality can also be a low or absent interest in or desire for sexual activity. A more encompassing approach to the term asexuality would be to consider it a spectrum of behaviours and sub-identities. “It’s an umbrella term that covers different, diverse, and sometimes inconsistent experiences, including ones that don’t perfectly hew to the “lack of sexual attraction” definition,” writes Chen.

Dismantling stereotypes: The diversity of asexual experiences

Chen emphasises that the ace community is not a monolith. Just as there is no one way to practise (allo)sexuality, there is no single archetype of asexuality which is the standard. Despite this, within and without the asexual community, there is often an ideal of what an asexual is supposed to be like.

This explicit and tacit acceptance of diversity in the asexual community was one of my favourite parts of Ace. Chen goes out of her way to include anecdotes from many different ace persons. Though of course, it is impossible that Chen would describe my exact experience, the book is written with such understanding and warmth that reading it made me feel accepted and respected.

This explicit and tacit acceptance of diversity in the asexual community was one of my favourite parts of Ace. Chen goes out of her way to include anecdotes from many different ace persons. Though of course, it is impossible that Chen would describe my exact experience, the book is written with such understanding and warmth that reading it made me feel accepted and respected.

Many asexuals feel like they do not belong anywhere because of imposter syndrome. Chen’s writing embraces and celebrates diversity and welcomes each and every questioning individual. This is why an encompassing and broad definition is crucial. We must not weaponise this term to be divisive or emphasise the difference. The point is rather to offer these labels to all those who would like to use and benefit from them. “The words are gifts…keys. Intellectual entryways to the ace world and other worlds. Offerings of language for as long as they bring value,” writes Chen.

Discovering asexuality: Comprehension and connection

Throughout the book, a commonality leapt out at me in the experiences of many asexual and aspec individuals. So many people found this word or concept and experienced immense relief, understanding and realisation. Discovering asexuality helped them realise something about themselves, to come to terms with their asexuality. They realised there was nothing wrong with them, that they were not alone, and they discovered a community. It changed their lives, for the better.

The near-universal ignorance of asexuality causes real harm, by restricting understanding and illumination, preventing asexuals from finding their community, and obfuscating healthier and safer possibilities for everyone. This ignorance is not a coincidence. This is something that the British philosopher Miranda Fricker has called hermeneutical injustice—the harm caused by being denied crucial information.

The near-universal ignorance of asexuality causes real harm, by restricting understanding and illumination, preventing asexuals from finding their community, and obfuscating healthier and safer possibilities for everyone. This ignorance is not a coincidence.

This is something that the British philosopher Miranda Fricker has called hermeneutical injustice—the harm caused by being denied crucial information. “(It) is a structural phenomenon. It is about marginalized groups lacking access to information essential to their understanding of themselves and their role in society—and these groups lack this information precisely because they are marginalized and their experiences rarely represented,” notes Chen.

In the allonormative society in which we live, information on asexuality is not readily available to the general public. Most people believe that it is normal to be sexual, to be attracted to other people, and to engage in sex. We also have very specific ideas of what constitutes normal sexual behaviour and activity, and are hesitant to step out of line.

This is because of compulsory sexuality, a concept inspired by the American poet Adrienne Rich’s essay Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. “Compulsory sexuality is a set of assumptions and behaviors that support the idea that every normal person is sexual, that not wanting (socially approved) sex is unnatural and wrong, and that people who don’t care about sexuality are missing out on an utterly necessary experience.”

Compulsory sexuality and asexual advocacy

In a chapter titled The Good-Enough Reason, Chen analyses the extent of sexual pressure that people are under. Merely not wanting to have sex does not generally suffice as an explanation in a society that considers having sex to be normal, healthy, essential and the peak of pleasure. This is why the work of queer and asexual activists is so important—it can be life-changing—not just for asexuals but everybody. It illuminates the powerful but invisible pressure of compulsory sexuality and empowers us to resist it.

“If anyone needs to make up an identity to get out of having sex, THAT is the bigger problem. It is a failure of society if anyone needs to say “I have a partner” to turn someone down, and it is a failure of society if anyone needs to invoke sexual orientation to avoid unwanted sex because saying no doesn’t do the job,” notes Chen.

Chen discusses how compulsory sexuality can make consent dubious when we acknowledge that there is an element of societal coercion present in every “normal” consensual sexual encounter. She cites the experience of a blogger who puts her acquiescence to sex in context.

Chen discusses how compulsory sexuality can make consent dubious when we acknowledge that there is an element of societal coercion present in every “normal” consensual sexual encounter. She cites the experience of a blogger who puts her acquiescence to sex in context.

“...doesn’t encapsulate the pressure and feeling of brokenness that I felt—the unspoken social norm that because I didn’t have a “good” reason to “deny” him, saying yes was a given. The problem is that I was left with no way to explain my hurt. On the surface, it shouldn’t have been a big deal: he said yes, I said yes, therefore everything was consensual. The problem is, had I known about asexuality, I would have said no. It felt like a wrong had occurred, even though there was no one to blame. And that is hermeneutical injustice.”

Asexual discourse and activism are crucial in challenging and hopefully dismantling these norms. Just as pervasive ignorance causes real harm, the knowledge of asexuality, and the self-understanding it grants, helps individuals find solace and self-acceptance. It empowers them to find a sense of belonging within the asexual community.

This account is a shock to the system. It demands that we reflect on compulsory sexuality, consider the state of social sexual norms, and look for the violence and harm present in “normal” sexual activity (it bears repeating—an encounter can be “consensual” and harmful).

Asexual discourse and activism are crucial in challenging and hopefully dismantling these norms. Just as pervasive ignorance causes real harm, the knowledge of asexuality, and the self-understanding it grants, helps individuals find solace and self-acceptance. It empowers them to find a sense of belonging within the asexual community.

Even for those who do not identify as asexual, engaging with asexuality can be enlightening, expanding understanding of human sexuality and calling for a more inclusive and accepting society. Ace serves as an essential resource, providing intellectual pathways to understand the multifaceted nature of asexuality.

Apart from the topics discussed in this review, Chen takes up several more in the book—not least among them de-pathologising asexuality, problematising “feminist” sexual liberation, delving into intersectionalities of asexuality with disability, race and gender, and the parallels between amatonormativity and allonormativity.

Ace is an excellent introduction to asexuality and its place on the wider spectrum of human sexuality. It is a mandatory read for anyone affected by sex and sexuality, which is, of course, everyone.

About the author(s)

Simran is a teacher and writer from Pune. They write about feminist issues from a philosophical perspective. They are committed to working on the issue of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). They love reading and learning languages (fluent in French, they are now trying their hand at Spanish and German). Simran has a BA in Philosophy from Fergusson College and a Masters in Cognitive Sciences from IIT Gandhinagar. They can be found on Instagram as @willtophilosophy, where they post about philosophy, literature and feminism.