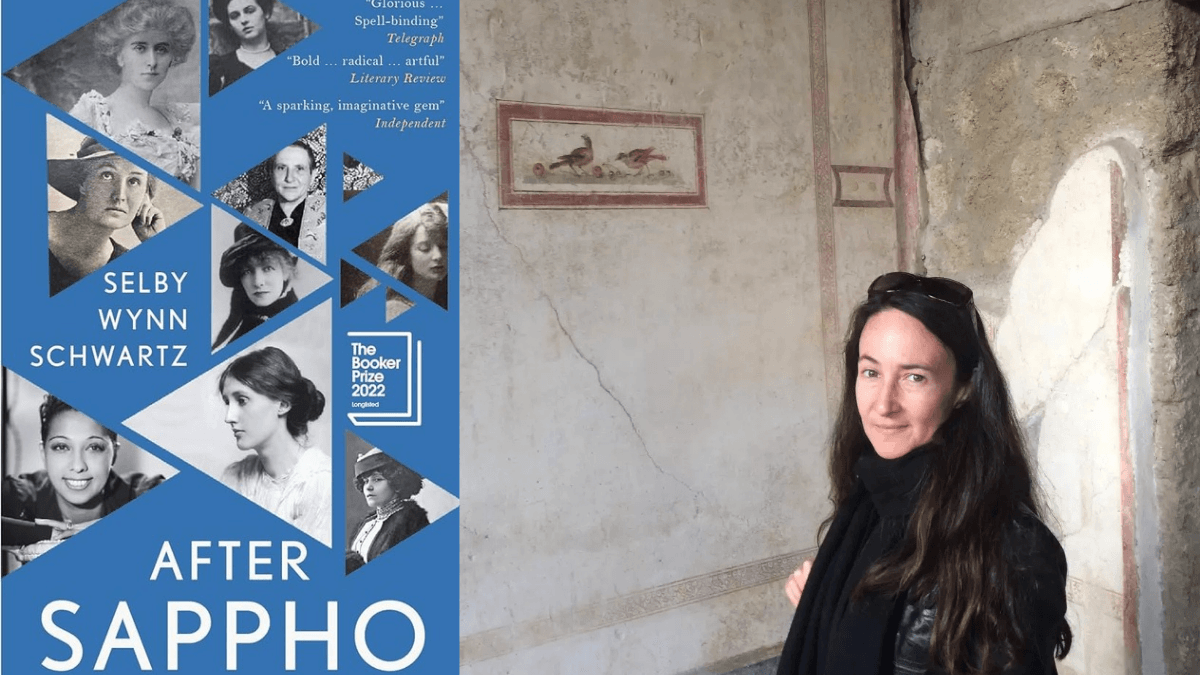

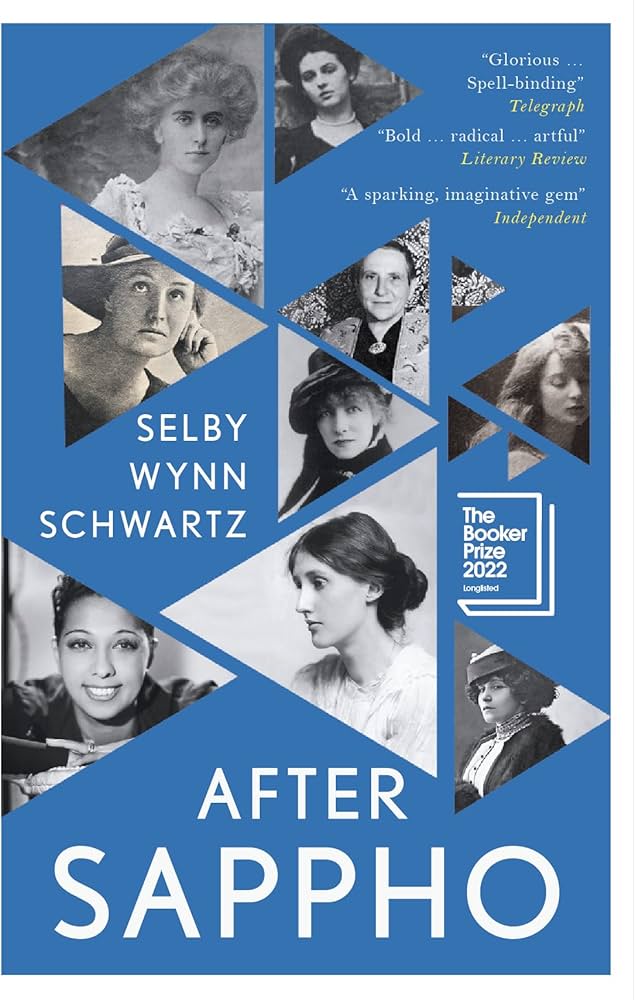

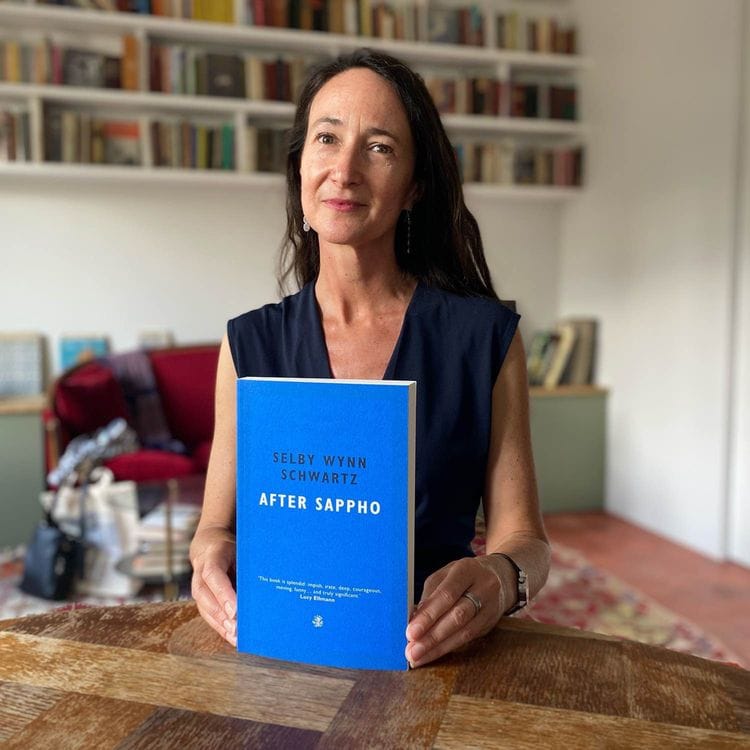

After Sappho was longlisted for The Booker Prize 2022. It was written by Selby Wynn Schwatz. The book circles around the lives of queer women intellectuals at the turn of 20th century, rooted in Europe. The author weaves a thread of stories, comprising the history of women hailing from the queer and feminist cultural past, proceeding from Sappho of Lesbos.

Schwatz’s narrative has been strongly driven by the joint energies of lesbian desire and fragments of anecdotes about real life modernist icons.

Schwatz’s narrative has been strongly driven by the joint energies of lesbian desire and fragments of anecdotes about real life modernist icons. The author provides a catalogue of embodied expressions of women yearning for women, through the gaze of women. The account talks about some established women like Virginia Woolf, Sarah Bernhardt, Lina Poletti to name a few.

We notice the most important thing about After Sappho is that Schwatz repeatedly uses a collective ‘we’ in the novel, which gives us a hint of feminist activation. The miscellany of ‘we’ transcends time and space, taking a forward march against various shades of misogyny, patriarchy and war.

The narrative style of After Sappho

Throughout the novel, we find various incomplete segments of Sappho’s poems which underlines the fact that Schwatz wanted the readers to be constantly ‘in touch’ with her. There is also an element of lesbian world-making which gets highlighted in every story. The author writes in Prologue of After Sappho, ‘The first thing we did was change our names. We are going to be Sappho.’

The intersecting histories, titled with names and corroborated with timelines makes the stories look closer to Sappho’s lyric. The author tried to form and reform Sappho’s fragments each filled with desire, longing and love. Schwatz pens down ‘Each one lingered in her own place, searching the fragments of poems for words to say what it was, this feeling that Sappho calls aithussomenon, the way that leaves move when nothing touches them but the afternoon light.’

Back in the 1900s, queer identity was seen apparitional and homosexuals were portrayed as enigmatic.

Back in the 1900s, queer identity was seen apparitional and homosexuals were portrayed as enigmatic. There are many instances in the book where women have changed their identities, transformed themselves, wrote under a pen name just to fit in the world that has consistently refused to accept their autonomy. The core content of the novel gives us a nuanced perception of feminism. But with more than fifteen women characters in After Sappho, written in fragments, it becomes very hard to keep track of every queer story. Maybe the author wanted to keep the spirit of Sappho alive, hence chose to write in pieces.

The theme of desire and representation of queer love is very evident in the book.

Isadora Duncan and Eleonara Duse, 1913

There is a very prominent section of intimacy between Isadora Duncan and Eleonara Duse in After Sappho. The author jots down-

‘Ancient Greek has a singular and a plural, as in other languages. But there is also the duel, which is used for two things that naturally occur together: twins, a pair of turtle doves, breasts, the two halves of a walnut in one shell. Do you see? Eleonara asked Isadora, looking up from the Greek grammar that lay open between them. Only for two things that embrace each other. As when you sleep in my arms, my sweet.’

Schwatz wanted to highlight the channeled version of Sappho through multiple consciousness of women in the early 19th and 20th centuries. The narrative is partly a speculative biography and partly an imaginative invention.

Natalie, Elisabeth and Romaine, 1918

In another instance, we observe a blooming romance between Natalie Barney and Eva Palmer. It was 1900. They encountered each other at a salon and the author writes ‘When Eva recited poetry, Natalie felt the silent crowd of trees bowing their crowns to listen…. Natalie embraced her: books, body, pine needles. They were young, but they were feeling their way towards becoming.’

There is a component of free love in the age of modernism. As we read later, we come across to the fact that Natalie Barney and the French princess, Elisabeth de Gramont wrote their marriage vows in 1918. Adding to that, Barney was already romantically associated with Romaine Brooks. But as we turn pages, we comprehend that in their own way, Elisabeth, Natalie and Romaine were together for almost forty years. Polyamorous relationships formed and dissipated with time, as we read further.

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, 1927

Next, we find Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West meets up in Schwatz’s novel. There’s a chapter where Virginia Wolf coined the term ”Jessamy”. It is an eighteenth century slang for lesbians. As Julia Briggs said, Woolf had titled The Jessamy Brides in 1927 and the sole purpose of the novel was to sketch a portrait for Vita Sackville-West.

As Julia Briggs said, Woolf had titled The Jessamy Brides in 1927 and the sole purpose of the novel was to sketch a portrait for Vita Sackville-West.

‘Sapphism is to be suggested. Virginia Woolf said to herself, and wildness‘ writes Schwatz. Virginia wrote a letter to Vita addressing that she could easily revolutionise the biography in a night, all she needs is Vita. Sackville replied back to her saying that Woolf might have every crevice of her, every shadow and string of pearlescent thought.

Of course, we know that there are several letters that were exchanged between the two. The letters and diary entries overflowed with love and admiration for each other. The novel traces various instances where every interaction made between them, echoes of fondness, warmth and tenderness.

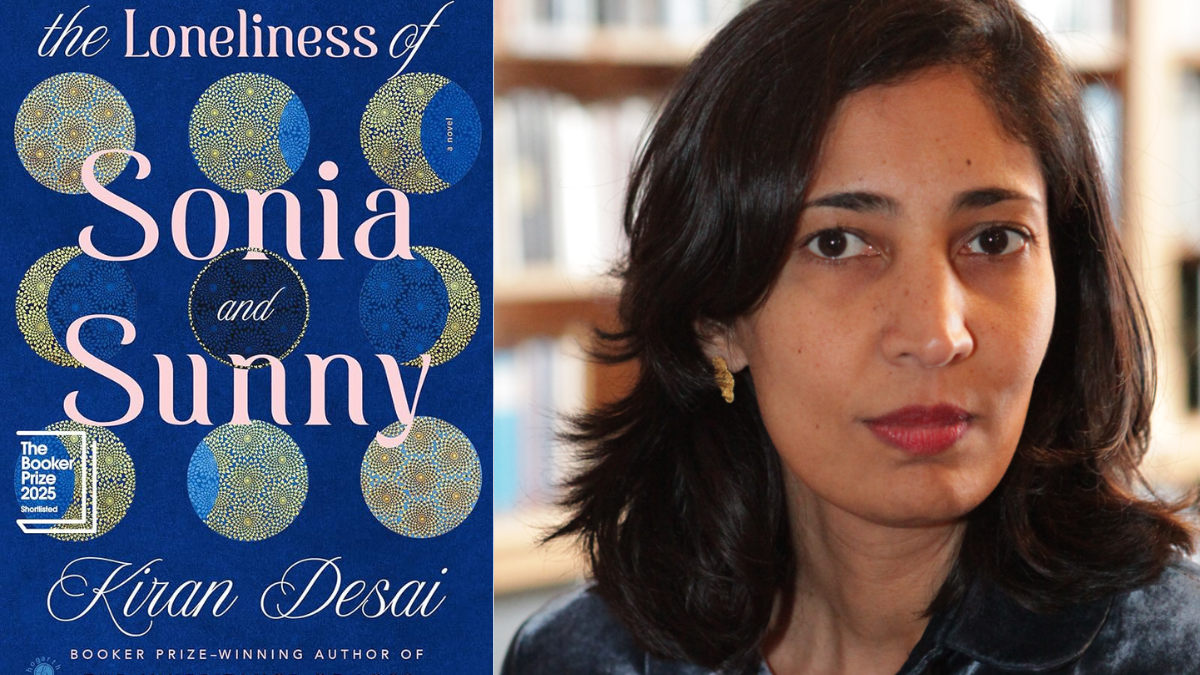

After Sappho: of endings

After Sappho ends in 1928 with Virginia Woolf publishing Orlando. There is a very famous statement made by Woolf in her book, A Room of One’s Own which is ‘Chloe liked Olivia‘ in the context of Mary Carmichael’s debut novel.

This statement has dared many women to come out about their sexuality and freely express their emotions. Mary and Woolf have thrown a light on the unexplored dimension of women’s lives, fundamentally changing the norms of writing. The depth of literary depiction of women loving women had not been attained before the statement came to the surface.

Schwatz records a very strong take in this historical fiction. She urges us to change our names, so that the story will feel our own. Chloe and Olivia could not claim their rights, but we can. Sappho is used as a flame, the beacon, which ignites the passion and love in the novel, transgressing social boundaries in the society.