Waste management is the process of managing waste from its collection to recycling. It embodies informality, long working hours, and unfair wages.

It is said that the informal sector contributes to waste management on a large scale. It might be true to some extent, but it aggravates the normalisation of the challenges faced by women waste pickers. This is how “informalisation” and women’s harsh experiences are interlocked.

It is imperative to discuss informalisation and how it is causing women waste pickers to be susceptible to exploitation. In keeping with the International Labour Organisation, women’s employment makes up 81.1 percent in India’s informal sector. During emergencies, they struggle to get leave as employers are often reluctant to accord them days off. It is worth mentioning that women constitute 5 percent in the formal sector, according to the Institute of Social Studies Trust.

In informal low-paying jobs, women do not have social security, and their employment remains invisible. Waste picking is also a part of it. The workers are not only looked down upon because of the notion of ‘impurity‘ attached to the job but are also exposed to gender bias and harassment. All in all, it is a complete invisibilisation of human rights.

Waste management is dominated by women, but harassment is ignored

Waste management is debated and discussed not only at the national level but also global. In the midst of this, it is very significant to talk about how waste is being managed. In India, managing millions of tonnes of untreated waste that generates health issues is a challenging task. People are more inclined to throw garbage than clean it up. If street workers do it on the streets, they are discriminated against by being termed as ‘unhygienic.’

On the one hand, research is done to recognise the contribution of women at the household level in managing waste segregation and its collection. Women’s domestic labour is said to commence the first stage of the waste management process; their active participation in recycling activities is also an integral part. In fact, Mapping the Status of Women in the Global Waste Management Sector was a global survey carried out by Women of Waste (WOW), which affirmed, “women contribute massively to the waste management sector in multiple roles across the waste management hierarchy, even though they are not very ‘visible.’” On the other hand, the sexual exploitation and harassment they experience and feel at their workplace is highly overlooked.

Female street waste pickers are often harassed on accusations of theft by the police when they collect garbage and endeavour to recover items that could be sold at recycling shops to get some pennies for their livelihood. Since the local government does not regulate their intensive and exhausting work, it becomes even more common to face accusations and harassment. These workers do not have other employment options due to a lack of education and skills. It is much easier to get into the informal sector than to seek job opportunities in another sector.

The Informalisation of the waste workforce affects the most marginalised

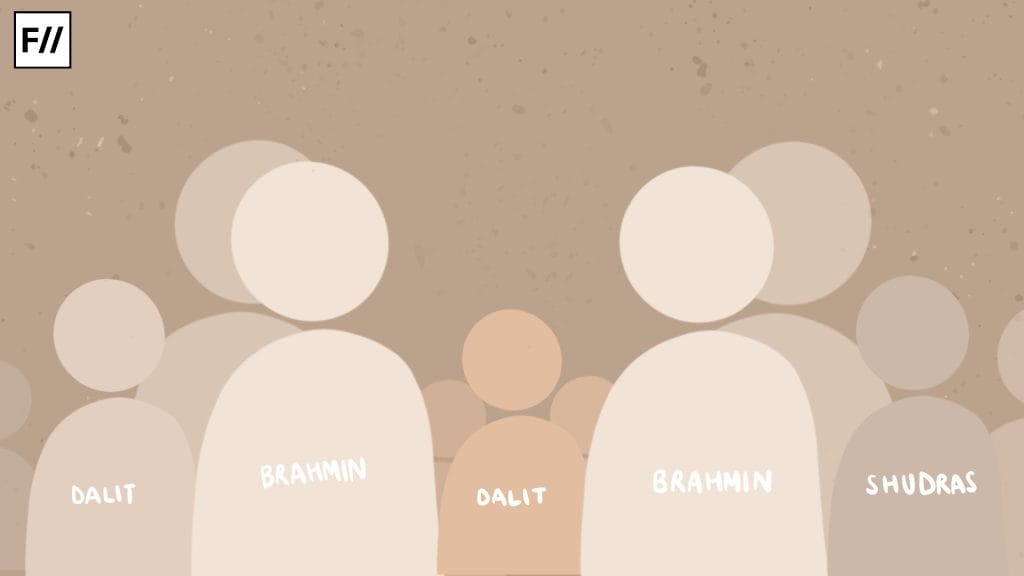

The composition of women waste workers comprises marginalised Dalits, poor Muslims, and immigrants. Most of them are Dalits in Bengaluru, whereas Bengali Muslims form the majority in Delhi. It is worthwhile to note that along with Dalits, Muslims and immigrants are also placed at the lowest rung of the socio-economic stratification.

After the comprehension of the composition based on the socio-economic status quo, it is important to shed light on women waste workers facing sexual exploitation in the informal sector. Exploitation takes its worst form if a person belongs to the lowest class and caste.

Managing waste is a significant concern in India. Despite this, the waste management sector is hierarchical in nature; that is, the riskier the work is, the lower the income is. There is research done titled “Migrants and Waste : A Gendered Analysis of Work, Identity, and Precarity in Urban Slums of Lucknow” on Bengali-speaking Muslim migrants from Barpeta in Assam who work as waste labourers in Lucknow. The reasons for their migration to a land located at a long distance are the harassment, denial of employment benefits, and land entitlements they encounter based on their lingual-ethnic differences. The women who accompanied their husbands to Lucknow have to face the gendered division of labour, which further makes them vulnerable to diseases. The women waste workers are placed at the bottom of the waste management sector compared to their husbands, who often get to work as door-to-door collectors. The former are more vulnerable to hazardous conditions.

The direct participation of the marginalised communities in the informal sector sustains their marginalisation further. Women workers are mainly seen as being engaged in collecting and segregating waste. The responsibility of waste segregation is primarily placed on women who are paid the lowest wages or sometimes receive nothing when they do the work at home.

The burden of economic constraints is put on women waste workers

In addition, female waste workers wake up early in the morning for many reasons; two of them are to prevent face-to-face interaction with the public who discriminate against and harass them and to balance their workload between waste work, household chores, and taking care of children. Furthermore, these workers are often exposed to domestic violence. The burden of financial constraints is on them; they face limitations in document identification, healthcare services, electricity, education, safety measures, sanitation, etc.

In the pursuit of earning a considerable livelihood, women labourers face huge challenges. The absence of initiatives to undertake measures to uplift them increases the informalisation of the waste management sector. As always, men dominate high-paying jobs, while women are stuck in the lowest-paying jobs because of well-embedded patriarchal structures that assert norms for women to choose traditional roles for themselves.

Henceforth, the informalisation of the waste management sector is not effectively addressing the problems stemming from waste dumps and landfills but is maintaining the traditional roles of women.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.