Discussions on reproductive rights are infrequent in everyday dialogue; however, their violations ought to be a significant issue on both national and global scales. According to the United Nations, reproductive rights are human rights. These rights are interconnected with other fundamental rights, including the right to life, the right to be free from torture, the right to education, and so on. Therefore, it is crucial to discuss their violations and condemnation in capitalist societies to accumulate labour to maintain the dominant power structure.

In the present time, capitalists do not want Dalit and Adivasi communities to have reproductive rights. In order to access unlimited cheap labour, the capitalist mode of production is against birth control methods to exploit labour power that is extracted from marginalised groups.

It is important to understand how Dalit and Adivasi communities are compelled to sell their labour power to capitalists for unfair wages. The nexus of informalisation and casualisation is growing, which brings in Dalit and Adivasi workers. Despite so much progress and technological advancement, well-embedded societal norms are still an obstacle to the marginalised upward mobility.

Before the initiation of arguments, we need to grasp how the informalisation of Dalit and Adivasi workers allows the capitalist structure to prevail for a long time. The informal sector cannot be understood as a discrete domain of self-employment. According to the research paper titled “Rise of Informalisation in Global Capitalism : Exploring Formal – Informal Linkages and Environmental Sustainability,” it is presented in the conceptualisation that the formal sector is the opposite of the informal economy, but both fall within the parameters of capitalism.

As a result of the interconnectedness between societal norms and large-scale urbanisation, a large number of workers belonging to Dalit and Adivasi communities are service providers and reproducers of the labour force, maximising profits to sustain capitalists.

‘Abortion is a Caste-Caste issue,’ in the capitalist world

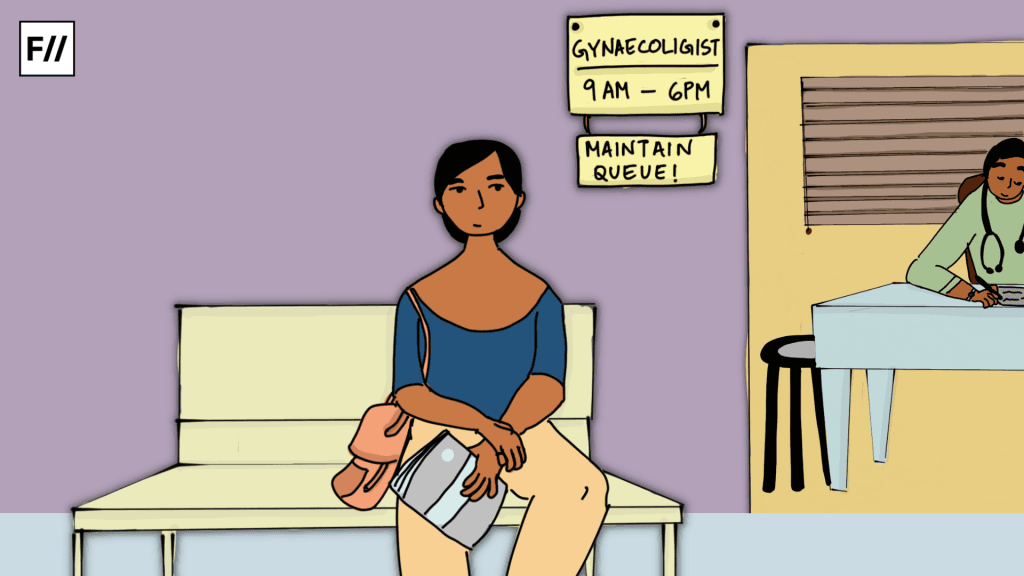

Abortion is detrimental to the capitalist structure. For its expansion and growth, a large number of workers are needed. Capitalism wants marginalised groups to reproduce as many workers as possible. The most prominent factor in considering abortion as a caste-class issue is that Dalit and Adivasi women are placed at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy. They face financial constraints if they want to abort unwanted fetuses. Due to this, they have to undergo unsafe abortions. In 2015, a study revealed that 78 percent of all abortions were carried out outside health care services; Dalit women were most affected. Public health care centres are not established for the marginalised due to their low caste and class.

It is evident that class and caste make abortion a struggle for the marginalised, although Indian feminism fails to advocate for their reproductive rights.Abortion is perceived as a privileged right, inaccessible to the marginalised who endure social stigma related to both gender and caste, in addition to financial limitations.

The foetuses that develop into children are forced to participate in the informal workforce. This workforce participation consists of unorganised, casual, self-employed, and migrant workers who belong to Dalit and Adivasi communities. Generally, these workers have no written contracts, no access to protection laws at the workplace, no right to organise, no pension, etc.; yet they are vulnerable to capitalist forces that especially want women workers to sell their labour at workplaces and reproduce workers at home. Historically speaking, the modern employment contract came into existence in the aftermath of the Second World War. It was planned to set the standard in developed countries in the world pertaining to job security, occupational safety, living cost adjustments, etc.The organised mass workers struggled to bring about changes in the formal sector, while the informal sector appears to be the norm for poor workers from the downtrodden sections.

Capitalists restrict the marginalised economically to increase worker production

Since informal workers from marginalised communities do not have rights, it becomes easier for capitalists to exchange labour power for minimum wages to accumulate wealth. These poor workers live in extreme poverty, and it is quite difficult, with these unfair wages, to earn a significant livelihood; there is no other option left but to produce children to help them with the hope of improving their lives. Further, these children, again, fall into the informal workforce because their parents cannot afford basic rights, such as education, healthcare facilities, and so on.

In the absence of organisations and unions for them, it is a challenging task to make women aware of their reproductive rights and how reproducing a large number of children breeds child labour rather than increasing wealth for a sustainable livelihood. In fact, there is a crystal-clear definition of child labour from the International Labour Organisation (ILO): “It is considered work depriving children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and harmful to their physical and mental development.”

According to Richard Wolff, “abortion rights are an anti-capitalist perspective.” When he was asked to make a connection between capitalism and the ability of political rulers to control women’s bodies, he replied, “Political rulers have no direct interest in controlling women’s bodies. They are much more interested in managing and solidifying capitalism, for which they seek bodies which are productive and make profits for companies.”

Henceforth, capitalism does not want women to have bodily autonomy. Recently, the chief ministers of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, Chandrababu Naidu and M.K. Stalin, asked women to have more children in order to benefit the nation. Reproducing children is one’s responsibility to provide “a service to society.” On the one hand, there are some factors, such as education, access to quality healthcare facilities, economic capital, etc., that drive a woman to have children. On the other hand, in spite of having so much progress in terms of low fertility rates because of quality education, healthcare benefits, etc., these calls to reduce women to reproductive roles and underestimate their consent are considered ‘a threat to decades of progress in the south.’

The separation of reproductive rights from socio-political discussions

It is not common to see discussions about reproductive health and reproductive justice in socio-political talks. It is even considered important to understand capitalism and reproductive rights as two unrelated categories. It is a mistake to think of capitalism as merely interfering in the economy. It also deals with socio-political aspects to smooth its function. It can use social stigma and societal norms to accumulate wealth.

There is a famous argument of Silvia Federici in her remarkable book Caliban and the Witch : Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation that the practice of witch-hunting has been a significant part of the advent of capitalism. According to her, witch-hunting cannot be assumed to have been an isolated event, but rather played an integral role in the development of capitalism through controlling women’s reproductive rights. It was deemed imperative to control women’s bodily autonomy to produce the workforce. The practice of witch-hunting was imposed on poor women belonging to peasant communities. Hence, this is a historical insight to understand that class and caste matter the most in capitalists’ attempts to suppress reproductive rights.

Likewise, Dalit and Adivasi communities are vulnerable to reproductive rights violations. There is so much exploitation that halts their upliftment. On the one hand, they are engaged in traditional roles as leather workers, manual scavengers, street waste workers, etc., in the informal sector. On the other hand, they face a complete violation of their human rights. Although their direct participation in traditional roles and the suppression of reproductive rights are interconnected, capitalism utilises a large number of workers in traditional occupations in the informal sector to produce wealth.

Absence of labour laws strengthens the capitalist forces to suppress reproductive rights

The absence of labour laws in the informal sector further strengthens the capitalist forces to suppress reproductive rights. There were 44 labour laws in India before the introduction of the four labour codes in 2020 : Code on Wages, Industrial Relations Code, Social Security Code, and Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions Code. These laws were called ‘historic‘ in favour of workers rights and seen as an effective reform; yet around 90 percent of workers in India in the informal sector do not have social security. They fail to provide social protection to informal labourers, primarily women.

In the absence of effective labour laws for informal workers, capitalism grows stronger, depriving socio-economically marginalised people of reproductive rights. As they are unorganised, capitalists have no fear of losing to their mass mobilisation.

It is not accurate to assert that people understand reproductive rights as human rights. Since debates and discussions on these issues are limited, it is a challenging task to gain insights into the complex nature of capitalism and its nexus with social stratification and the control of women’s bodies. Moreover, labour laws are not formed with workers’ consultation and are not meant for labourers who are forced to sell their power to sustain their poor livelihoods.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.