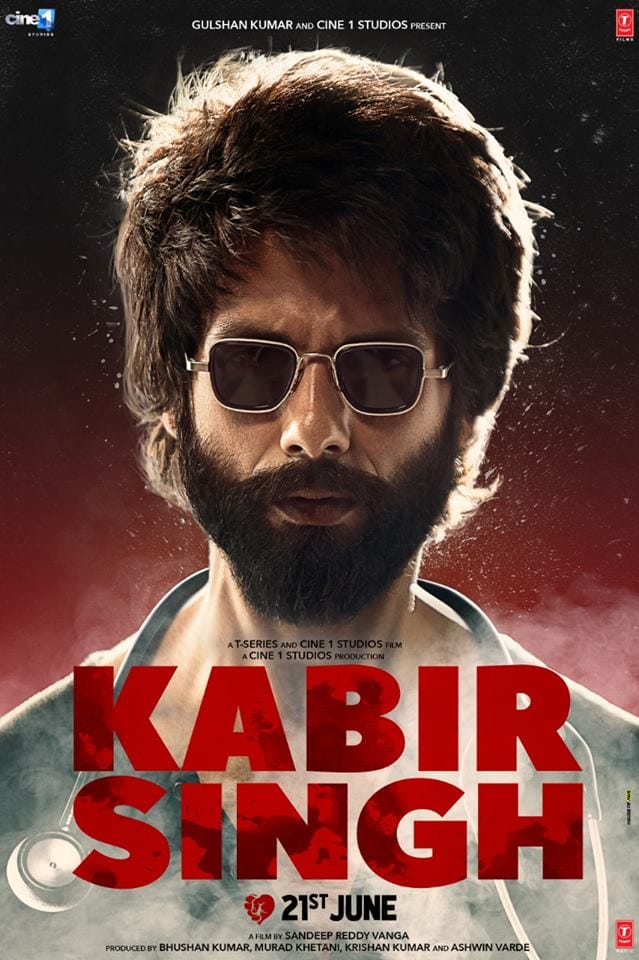

The cultural and commercial success of Pushpa 2: The Rise, Shahid Kapoor’s Kabir Singh, Ranbir Kapoor’s Animal, Yash’s K.G.F and the sustained popularity of hyper-masculine heroes among the Indian audience raises perplexing questions and signals trends that beg probing. What explains the sustained global appeal of these films? Does the answer lie in the patriarchal Indian culture and the male-dominated industry that provides a twisted representation of masculinity?

What explains the sustained global appeal of these films? Does the answer lie in the patriarchal Indian culture and the male-dominated industry that provides a twisted representation of masculinity?

Partly, yes but is it an adequate explanation? Is it a bleak reminder of the backlash feminism has received over the recent years from all quarters. It is necessary to eschew from offering a moral critique of these films and instead pay attention to the socio-political milieu of these projects. In discussing films, masculinity and its crisis, it is important to read these trends as a “cry for help”, ironically, for what masculinity is in dire need of- the gentle yet powerful embrace of feminism.

The trinity of masculinity: “bhai”, “patriot” and “romantic”

Toxic heroes have existed in the past. In the previous decade, Salman Khan’s “Bhai” persona fuelled this “big macho guy” trope with films like Wanted and The Tiger franchise that laid a template for the Alpha male. Then, in the 2010’s Bollywood too took a populist turn reflecting the political changes since 2014. Politics and cinema became intrinsically intertwined. Akshay Kumar became the posterboy for this new brand of films that bolstered the ambitions of a hyper-masculine nation in the signifier of a ‘relentless patriot’.

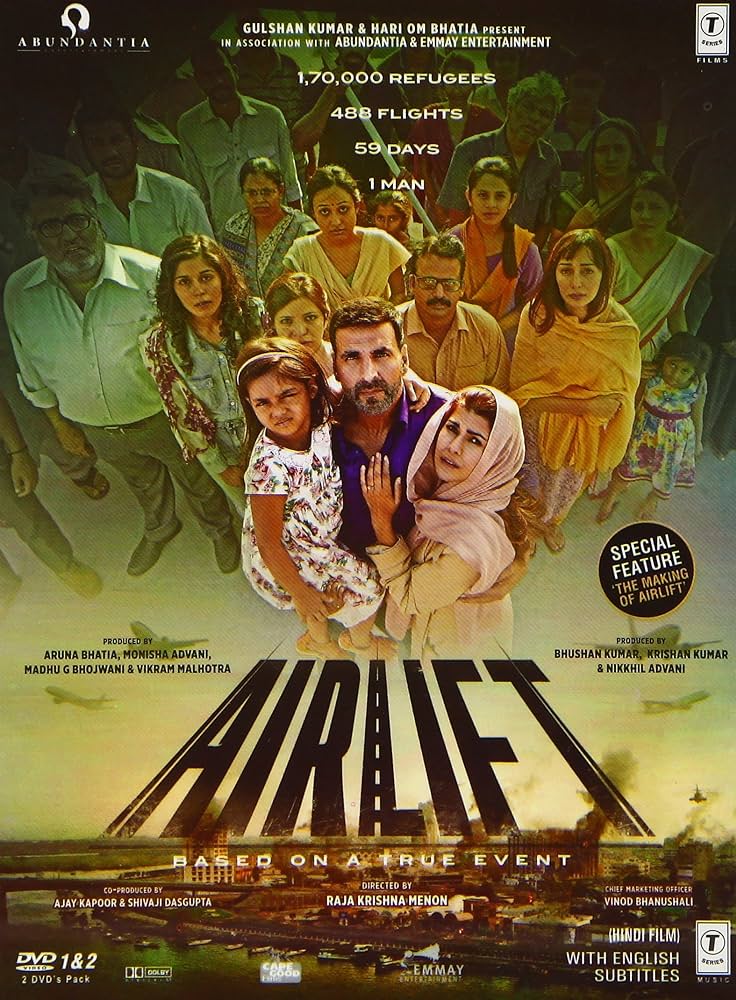

Films like Airlift, Baby, Padman, Sooryavanshi, Mission Mangal among others aimed to generate an affective popular consent for the political regime. Another softer version of masculinity exists with Shah Rukh’s passionate, relatively selfless, gentle masculine hero- “the romantic”. However, after successive commercial failures of films like Dilwale, Jab Harry met Sejal, Zero and political compulsions SRK also picked up on the masculine-nationalist bandwagon albeit, with King Khan’s twist with blockbusters like Pathaan and Jawaan.

Thus, these three forms of masculinity- “the bhai”, “the patriot” and “the romantic” have set the tone for a long while only to witness a massive commercial and cultural disruption in the past decade. This new hero has unlocked a new form of masculinity representative of the current times.

The “rebel” (without any cause): popular and populist hero

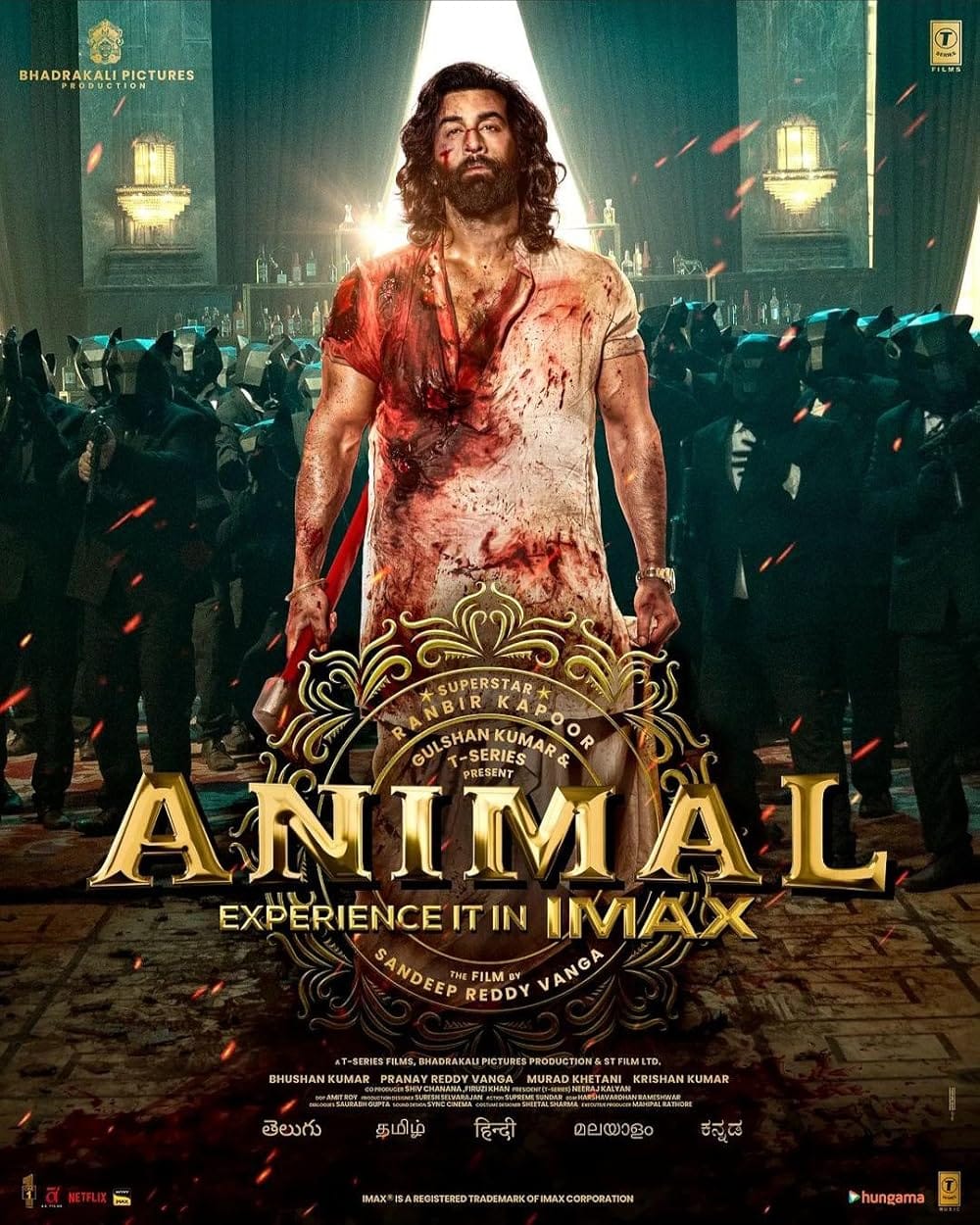

The different eras of masculine heroes that have dominated the cinema scape has contributed to the progressive dumbing down of the hero over the decades. Against this background, films like Baahubali, KGF, Pushpa and Vanga’s Hindi remake of Arjun Reddy and Animal among others, have unlocked a new Hero, “a rebel without any cause” for whom violence is not merely instrumental but essential for his existence. South Indian films primarily Telugu cinema has achieved a pan-Indian status. It has developed in the audience, a taste for exaggerated masculine overtones, fantastical violence and crass female objectification.

The writers compensate for the poorly written characters who lack any emotional depth with the use of loud, glorified and spectacle-like violence that juxtaposes the protagonists’ ordinary grim reality against his god-like powerful aura. This new “rebel” is an anti-hero with a fragile masculinity who is a lawbreaker finding thrill in outsmarting the cops; possessing an all-consuming sense of victimhood; an outsider and a disruptor who is almost too self-righteous to function without breaking a few bones!

This new “rebel” is an anti-hero with a fragile masculinity who is a lawbreaker finding thrill in outsmarting the cops; possessing an all-consuming sense of victimhood; an outsider and a disruptor who is almost too self-righteous to function without breaking a few bones!

The protagonist does not play by the rules but makes his own rules instead. Populist in its impulse, he is a rogue who subverts institutions, challenges the elites and speaks in the name of his “followers”. This rebel is not interested in making any socio-political statement or vision like the “Angry young man” of the 1970s did, yet, he is popular. His narcissism and self-righteousness cloak the blatant hypocrisy that lies at the core of our new hero but he is afterall, “the (man)child of his times”.

High on symbolism without much substance, the new “rebel” is the personification of a patriarchal populist who just doesn’t seem to win despite authentically being himself as he was told by the new system in the “new India”. Extrapolating this argument to ask a larger question: is the hurt pride of the majoritarian Hindu unable to find a closure in the actual political realm even after a decade? He has over-consumed the populist rhetoric peddled to him by mainstream media but does not see the ache din he was promised a decade ago.

Therefore, it could be argued that these films have a popular resonance since they facilitate the existing populist impulses in us to live on in the cinematic reality. Moreover, the normalisation of violence today against the marginalised Muslims and dalits in particular has kindled the dystopian fantasies buried deep in the human psyche which the cinematic landscape of today satisfies with its grotesque depiction of violence. The audience revels in the lawlessness and destructive anti-establishment sentiments nurtured on screen that draws parallel to their reality in the “new India”.

The audience revels in the lawlessness and destructive anti-establishment sentiments nurtured on screen that draws parallel to their reality in the “new India”.

Thus, watching the outsider, once vulnerable to upturn his destiny with now “morally legitimate” violence, finds cheerleaders among young men that these films primarily cater to. It also gives them a sense of pleasure and a momentary escape from the powerlessness they feel in real life. Eshan Sharma proposes that the films today provide an ‘escapist outlet‘.

Thus, the popular allure of these films signals an opulent indulgence in populist fantasies that has procured political salience since 2014, but it also glaringly highlights the persistence of the phenomenon of a crisis of masculinity that the former has only exacerbated.

Acknowledging the actual plot: crisis of masculinity?

The protagonists in the films mentioned above are emotionally stunted and vulnerable bearing the baggage of a dysfunctional family, shunned by the society and are in a pursuit for glory and acceptance from it. For instance, in Pushpa the titular character is a labourer who rises through the ranks in the red sandalwood smuggling syndicate with his cunning and bravery. Despite having incredible power he fails to gain the acceptance from his own family that he was seeking to begin with.

In Animal, the protagonist Ranvijay’s (Ranbir Kapoor) troubled relationship with his father, his craving for his attention and validation turns him into a violent individual. The female characters in these stories are mere “love interests” who offer an emotional arc to the story and become objects of fascination in the protagonist’s own quest for recognition.

Naseeruddin Shah, in an interview, attributed the growing number of this specific hyper-masculine brand of films to the increasing insecurity of men. Therefore, the ability of these hypermasculine heroes to touch the hearts and minds of young men must be acknowledged. These young men have an uncritical admiration for these pop culture icons, from imitating their choreography and lip synching to dialogues on social media to becoming Kabir Singh and Pushpa-like personalities in real life.

Thereby, posing a grave challenge to ideals of gender justice. These films reflect a certain ‘crisis of masculinity‘. The sociocultural restructuring of gender norms and identities have resulted in a spiraling moment for young men today. Further, the almost-crumbling global economic order has left many unemployed, morally defeated and feeling powerless in a system that has supposedly “intentionally” wronged them. Thus, seeing women take up the jobs and privileges that they were “originally” entitled to fuels much of the vicious backlash.

Further, the almost-crumbling global economic order has left many unemployed, morally defeated and feeling powerless in a system that has supposedly “intentionally” wronged them.

The emergence of the ‘manosphere’ online has crossed over to the real world today. These men are likely to pick up extreme ideological worldviews that find an outlet in populist demagogues like Trump. Thus, the repercussions of this crisis are hard to ignore. A 2023 study found that men join the manosphere due to their low self esteem and experience of romantic rejections. Additionally, “manfluencers“, the prominent figures of the manosphere, who advocate narrow ideals of masculinity and strong sexist perspectives on women have weaponised masculinity. They present an aspirational yet achievable personality of “alpha” male to capture their audience.

Millions of men look up to “self-help” gurus like Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan and Andrew Tate who weaponise male insecurities and direct their anxieties against feminism and gender justice. Thus, it is a concern for feminists to address this problem head on. While feminism has enabled women to express their insecurities and vulnerabilities in healthier ways, building solidarities and friendships among women, men find themselves in a precarious position. The manosphere then becomes a space for venting their frustrations and lending a community-feeling that soothes the hurt masculinity.

Way forward?

Betty Friedan wrote: ‘Men weren’t really the enemy. They were fellow victims suffering from an outmoded ‘masculine mystique’ that made them feel unnecessarily inadequate when there were no bears to kill.‘ Thus, men are also victims of societal expectations and stereotypes. The traditional model of masculinity is not serving them either. The fight for gender equality must encourage empathy and understanding between genders recognising its “equal but differentiated harm”. These social instabilities and churnings can become opportunities to remodel gender relations for the future.

Masculinity needs a rethinking, it is fragile but malleable. It is also pertinent in the Indian context to understand the intersectionality of caste and class in determining responses to and responses of a certain kind of masculinity. Masculinity needs a feminist makeover. Rebuilding a healthier version of masculinity that instills an ethical compass addressed by principles of social justice is necessary. The dearth of healthy heroes of masculinity and the discourse surrounding it is a challenge that needs to be overcome at the earliest.

However, the commercial success of films like 12th Fail and Laapataa Ladies is a pleasant reminder that there is still hope for alternative forms of masculinity. Therefore, one must not stop at merely “calling out men” instead invite them to conversations and enable them to explore their masculinity in healthier ways. In conclusion, men are trying to constantly cope with the troubled times, consuming hyper-masculine films like participation in the manosphere becomes a convenient outlet. Films often hold a mirror to society and also reflect their uncomfortable truths, it is imperative therefore, to look through the appeal of these films to unearth them.