Jineology, the “science of women and life,” came into mainstream discourse in 2011, with the making of the first Jineology committee. It described women’s subjugation as interlinked with nature and criticised western liberal bourgeois feminism, which alienated both the global south’s women and ecology, and took a decolonial, socialist and environmental approach to look at women’s subjugation. From then on, its research work has gone hand in hand with the opening of women’s education centres, academies, schools, and grassroots movements, mostly in Rojava but also in other Kurdish regions and Europe as well.

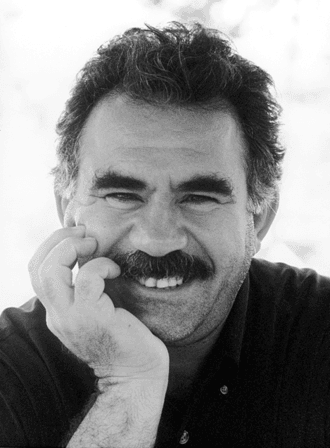

The discourse of Jineology presented by the Kurdish Women’s Movement as the result of gender alienation from the movement was inspired by various female leaders of the Kurdish movement and PKK (Kurdistan Workers’s party). Sakine Cansiz (Sara), co-founder of the Party played a crucial role in the discourses of Jineology with famous revolutionary leader Abdullah Oclan.

Oclan’s philosophy looks at women’s alienation from all public spheres and he also from an ecofeminist lens analyses the past. Later on, women leaders of PKK, based on this discourse, rethink the relationships between life-woman, nature-woman, and social nature-woman, to understand the culture and subjugation of women. They analyse the past of the pre-patriarchal society of ancient Mesopotamia. Also, they reflect on the matriarchal cultures of ancient Kurdish civilization which today in many villages of Kurdistan continue this legacy through oral folk traditions and literature.

Shift from Leninist-Marxist approach to women’s emancipation

Oclan, the leader of PKK, like other Marxists used to believe that women’s questions would be solved later on after the revolution. But after coming into contact with the work of ecofeminists like Maria Mies and others, he and other women leaders came up with the praxis of Jineoloji or Jinology.

The shift also suggests that women’s liberation is not secondary, but it should go hand in hand with revolution. Women leaders of the movement analysed women and nature’s oppression was not based on the western ecofeminist idea only but also included the legacy of ancient Kurdish matriarchal cultures.

Capitalist patriarchy as a source for women and nature’s oppression

Within the context of capitalist patriarchy, the oppression of both women and nature is embedded in a capitalist framework that results in both economic and social exploitation. This argument is backed by Maria Mies who states that patriarchy is not simply a culture or ideology, but rather a capitalistic system that is rooted deeply within the material structures of capitalism itself. It guarantees the erasure of women’s reproductive and domestic labour, as well as the profit-driven exploitation of mother nature.

Through the lens of Abdullah Öcalan, this argument is taken further when he notes that women throughout history have been the first to be synthetically colonised, which served as the flagship for the real commoditisation of land and labour. In his view, capitalist modernity is an advanced form of colonialism that rests on the dual domination of gender and nature, as their being dominated furthers economic productivity. It is a hierarchy where men dominate at the top and through systemic oppression exercise control over bottom-tier women.

Housewifisation is a process in which women’s labour and work are invisible, ensuring their financial dependence on men while simultaneously benefiting capitalism.

Moreover, capitalist patriarchy weaponises economic dependence in ways that scatter oppression across different structures. For instance, women are bound to do unpaid domestic work or face abusive working conditions that serve the system by exploiting their subpar status. Similarly, nature is reduced to a commodity, with deforestation, resource extraction, and industrial expansion occurring at the cost of ecological balance.

The dismantling of capitalist patriarchy requires a radical restructuring of both economic and social relations. By challenging its foundations, movements advocating for gender justice and environmental sustainability seek to create systems rooted in equity and mutual respect. Recognising the interconnectedness of these struggles is crucial in resisting the exploitative forces that define capitalist modernity.

Housewifisation: Oclan and Mies’s arguments over women’s subjugation

Jineology also talks about the concept of housewifisation, which has its roots in Maria Mies’s work Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale (1994). Abdullah Oclan taking forward Maria Mies’s argument posits that capitalism is inherently dependent on the unpaid labor of women, particularly in the context of the domestic sphere. Housewifisation is a process in which women’s labour and work are invisible, ensuring their financial dependence on men while simultaneously benefiting capitalism.

Mies believes that in capitalism, productive labour—identified with waged work—is predominantly masculine, while reproductive labour, carried out predominantly by women, is relegated either to the status of a natural role or is entirely regarded as no contribution to the economy. The bifurcation creates a hierarchy in which men dominate political and economic spheres, while women are relegated to the household. Mies criticises mainstream Marxist and ecological views for their failure to appreciate how capitalism exploits for free the work of women, much as it exploits nature.

She articulates a connection between housewifisation and colonial exploitation, arguing that just as capitalism draws surplus wealth and resources from colonised regions, it appropriates women’s labour without proper compensation. The Global South is manifestly cheap labour engaged in an economic task while clicking the paid element through different labour mechanisms, still conducting domestic work. Mies shows how development policies and neoliberal globalisation reinforced housewifisation by pushing women into precarious, low-wage jobs and maintaining their unpaid domestic responsibilities.

For Mies and Oclan, the deconstruction of housewifisation is crucial for women’s liberation. Thereby, she insists on the recognition and valorisation of reproductive labour and suggests that women should resist and/or dismantle capitalist structures that depend on the economic subordination of women to promote alternative economies based entirely on subsistence production instead of profit generation.

Jineology and ecofeminist emancipation of women

Ecofeminist emancipation means a worldview wherein women’s liberation cannot be divorced from ecological and social justice. Allowing women the proper context to reclaim their agency in reeling back capitalist modernity and patriarchy in some sense means that self-sufficient economies are created while resisting commodification and having a communal way of life that accepts nature and social interdependence.

Central to this vision is the idea that to be emancipated, these structures must be dismantled if they exploit both women’s labour and nature. In places such as Rojava, ecofeminism has a presence in women’s cooperatives, ecological agriculture, and alternative educational models. These assure the restoration of women’s autonomy in developing decision-making processes for local needs, not just a mere peripheral object in socio-political life.

Ecofeminist emancipation critiques the hierarchical separation of humanity from nature, which for centuries has justified environmental destruction-the unjust sterilisation of women. Ecofeminist movements restore the feeling of connectedness: sustainability is no longer an abstract goal but a lived practice tempered in everyday life. The emphasis on decision-making at the grassroots, land stewardship, and sharing knowledge renders credible the thought that a sustainable society can emerge only when women are free from patriarchal domination.

Finally, ecofeminist emancipation suggested by Oclan and Kurdish women‘s discourse of Jineology is a way to reappropriate power over both land and life. It seeks not only to resist capitalist exploitation but also to actively create a future in which the knowledge, labour, and leadership of women will be used towards making communities fair and ecologically just.

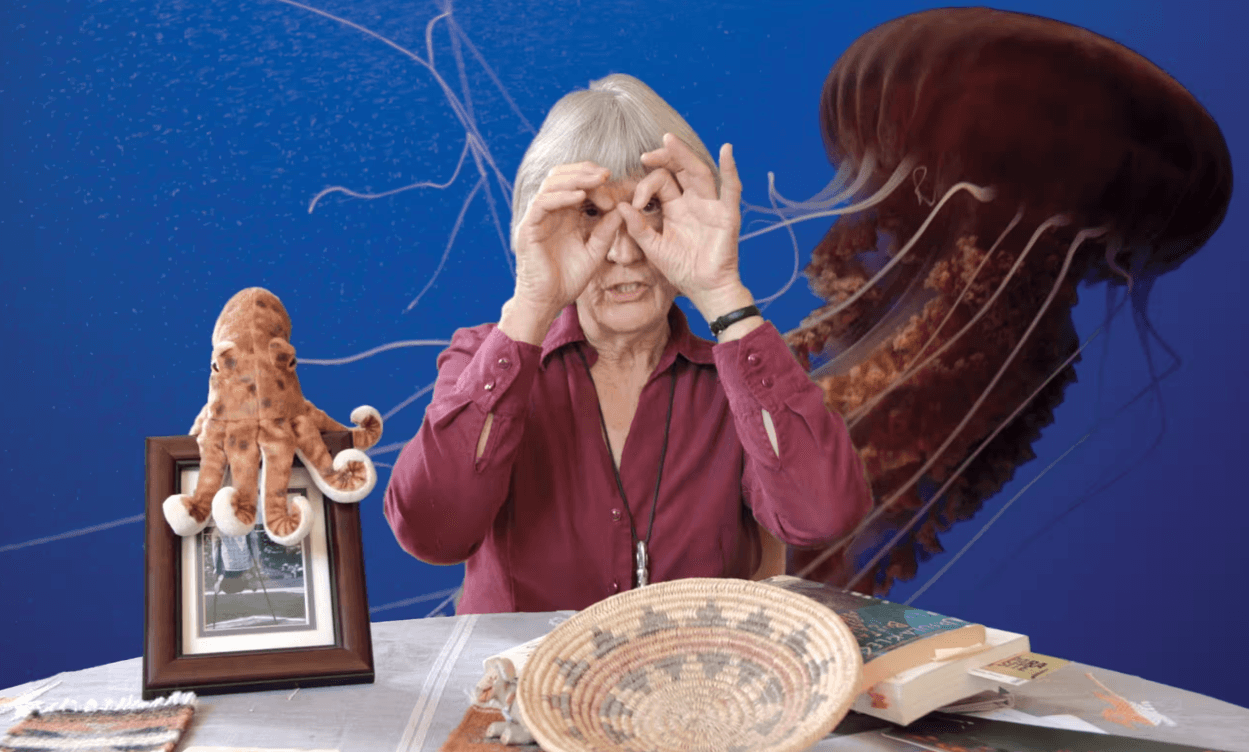

About the author(s)

Faga Jaypal is a final year history student at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, with a keen interest in intellectual history, gender and sexuality studies, social justice, and cultural studies. Passionate about literature, books, and museums, he combines his love for storytelling with academic research. Aspiring to become a teacher like Mr. Keating, he seeks to explore history through diverse narratives.