Women-led environmental activism in India can be traced back to the Chipko Movement in the 1970s. Important for its mobilisation of rural women, the Chipko Movement was one of the first acts of environmental activism that vocalised concerns against the state’s indulgence in excess capitalism.

A protest against the deforestation of acres of land that led to devastating floods and landslides, it has now become an exemplary event of grassroot environmentalism. In the recent years, voices like Medha Patkar, CK Janu, Mahasweta Devi and Arundhati Roy have played very important roles in several ecofeminist movements throughout the country.

Ecofeminism connects the domination and oppression of women, with the rampant exploitation of nature through masculine methods and attitudes. Environmental activist and author Vandana Shiva states that “while gender subordination and patriarchy are the oldest of oppressions, they have taken on new and more violent forms through the project of development.”

According to her, the feminine principle of Prakriti is a tool to counter the model of Western development, which she describes as “maldevelopment.” Ecofeminist movements have become an integral part of intersectional feminism in India. A movement like the Narmada Bachao Andolan is an example of enabling voices of tribal and Adivasi women.

Literature and environment-centric storytelling

Environmental literature has also significantly contributed to the prominence of ecofeminist movements in the country. While environmental writing can be of many types, the pieces of Indian literature that emphasise environmental concerns have created long-lasting effects. Male writers of the past like Bibutibhushan Bandhopadhyay, and more recent authors like Amitav Ghosh, have criticised in their novels, our corruption and exploitation of nature.

Bandopadhyay’s Aranyak or Of the Forest shows the contradictions of urbanity against the natural. Satyacharan, the novel’s protagonist first struggles to let go of his urban lifestyle and in later hypnotised by the jungle. On the other hand, Amitav Ghosh shows the human crime against nature that leads to mass destruction. In his books, the colonial past and the nature merge into one another while marginalised communities take the center stage to tell the stories of their unique environments.

Anita Desai’s 1978 Sahitya Academy Award winning novel Fire on the Mountain connects the physical and mental abuse of three women with the oppression of nature. In this novel, men being part of the bourgeois structure are agents of domination, fear, hate and brutality while nature and ecology is interrelated with women and the non-human. In the face of extreme exploitation, the darker and more sinister aspects of both women and nature are revealed throughout the course of the novel

In The Hungry Tide, Piya is our entry pass into the Sundarbans, but it is Fakir and Nirmal’s experiences that give us an in-depth understanding of the corruption of nature and it’s immediate affects.

Though these authors among many others, and their works, place the intersection of the environment and people’s rights at their center, it is only when we look beyond the dominant canon of masculine literature that we discover the ecofeminist writings of female authors. They not only criticise the anti-environmental, capitalist practices of the governments, but also give voice to the underprivileged with a crucial gender lens.

Also read: Hands On: A Documentary On Climate Change By Five Women From Four Continents

Fiction and environment: The significance of ecofeminist stories

Published in 1954, Kamala Markandaya’s first novel Nectar in a Sieve deals with man’s primitive bond with nature. The introduction of industry and technology in the form of a tannery results in the destruction of the austere, pastoral rural life. The tannery that is shown to be built under the supervision of White men and supported by the zamindars, becomes a symbol of patriarchy. While industrialisation leads to the development of the town, it also forces peasant women to take up prostitution out of unemployment.

Anita Desai’s 1978 Sahitya Academy Award winning novel Fire on the Mountain connects the physical and mental abuse of three women with the oppression of nature. In this novel, men being part of the bourgeois structure are agents of domination, fear, hate and brutality while nature and ecology is interrelated with women and the non-human. In the face of extreme exploitation, the darker and more sinister aspects of both women and nature are revealed throughout the course of the novel.

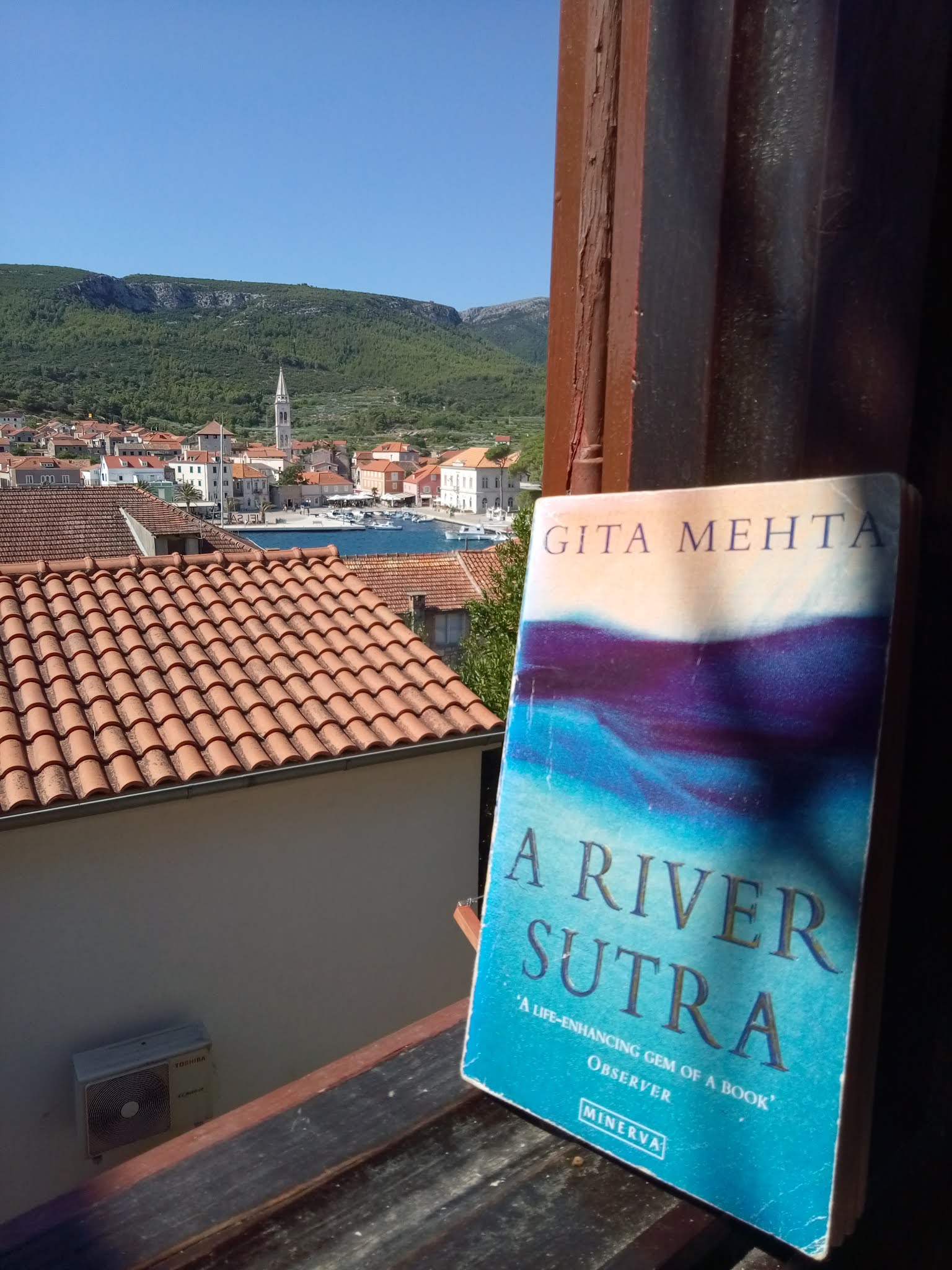

A River Sutra by Gita Mehta is a collection of six short stories that was published when the Narmada Bachao Andolan was at its peak. The Narmada river, which serves as a natural boundary between north and south India is not just a site of biodiversity. Beyond its anthropological, agricultural and ecological significance, it is also a site of cultural importance.

The dam construction on the river leads to the destruction of the cultural history of the natives who previously inhabited the land. Mehta rejects the patriarchal idea of the river being weak, passive and fragmented and through her collection, envisions the feminine principles of Narmada as a chief life source.

Ecofeminist writings are essential for the inclusion of intersectionality in Indian feminism. Fiction is often sidelined as being of now more value than indulgence. But fictional ecofeminist literature, particularly authored by women, etches out the nuances of the intersection of the environment, pollution, urbanisation and climate crisis with gender through narratives that are more personal and therefore, more relatable

While Arundhati Roy’s 1997 novel The God of Small Things critiques the irreparable damages of the misleadingly named Green Revolution, at the heart of the novel is the counter movement against Indira Gandhi’s proposition for development. The Green Revolution yielded crops that staved off famines but it lead to severe ecological damages, the brunt of which was faced mostly by the oppressed caste communities and women.

Of more recent ecofeminist writings in literature, we have Anuradha Roy’s An Atlas of Impossible Longing, and Usha K.R’s Monkey Man, to name a few. They deal with women’s relationships with urbanisation. In developed or developing cities, women are given so called equal opportunities that reflect a universal globalisation. These novels dig deeper and unearth the uncertainty that the urban landscape provides. Away from nature and culture, it becomes a site for both creation and destruction that echoes a sense of madness which is particularly taxing for women.

Ecofeminist writings in post independence India link patriarchal violence inflicted on nature that began with the colonisers’ dream of Westernisation with the generational brutality faced by women of India. Ecofeminist literature and discourses aim not to give voice to the urban caste and class privileged individuals but to the individuals pushed to the end of the line.

Ecofeminist writings are essential for the inclusion of intersectionality in Indian feminism. Fiction is often sidelined as being of no more value than indulgence. But fictional ecofeminist literature, particularly authored by women, etches out the nuances of the intersection of the environment, pollution, urbanisation and climate crisis with gender through narratives that are more personal and therefore, more relatable.

It is a way to give as Mahasweta Devi said, “the voiceless a voice.”

Also read: Climate-Fiction: Creating Stories Out Of Catastrophe

Featured Image Source: Rawpixel

About the author(s)

Udhriti Sarkar is a post-graduate student at Calcutta University. When she is not obsessing over fictional characters, she observes people and writes about them