Women have played a vital role in shaping the past, present and future of Indian cinema. Generally, the role of female artists has been discounted or marginalised in the annals of history because of the generally andro-centric gaze of historical introspection. Women had to face a lot of struggle to make their niche in the Indian film industry but there were women who became the face of the cinema. The history of cinema remains incomplete without taking cognisance of the role played by women in its production, dissemination and consumption.

When the Indian film industry was brought into existence in 1913 by Dada Saheb Phalke, the theatrical world was generally dominated by men, so much so that there were professional male cross-dressers who played female characters as there was lack of women in the theatre (as it was seen with contempt in the traditional patriarchal society). Thus, in the first feature film of India titled Raja Harishchandra, the female characters were also portrayed by men. It was later in 1914 that women became a part of cinema with Phalke’s film Bhasmasura Mohini. The first female actress in Indian cinema was Durgabai Kamat, who in more than one way challenged the rigid patriarchal society. She was a single mother, a divorced woman who chose theatre as a career despite being ostracised by his fellow Brahmins as well as the cross-dressers, for whom it was a loss of employment. Durgabai Kamat not only herself played the lead role in the film but her daughter Kamlabai also played a small role, becoming the first female child actor in the process.

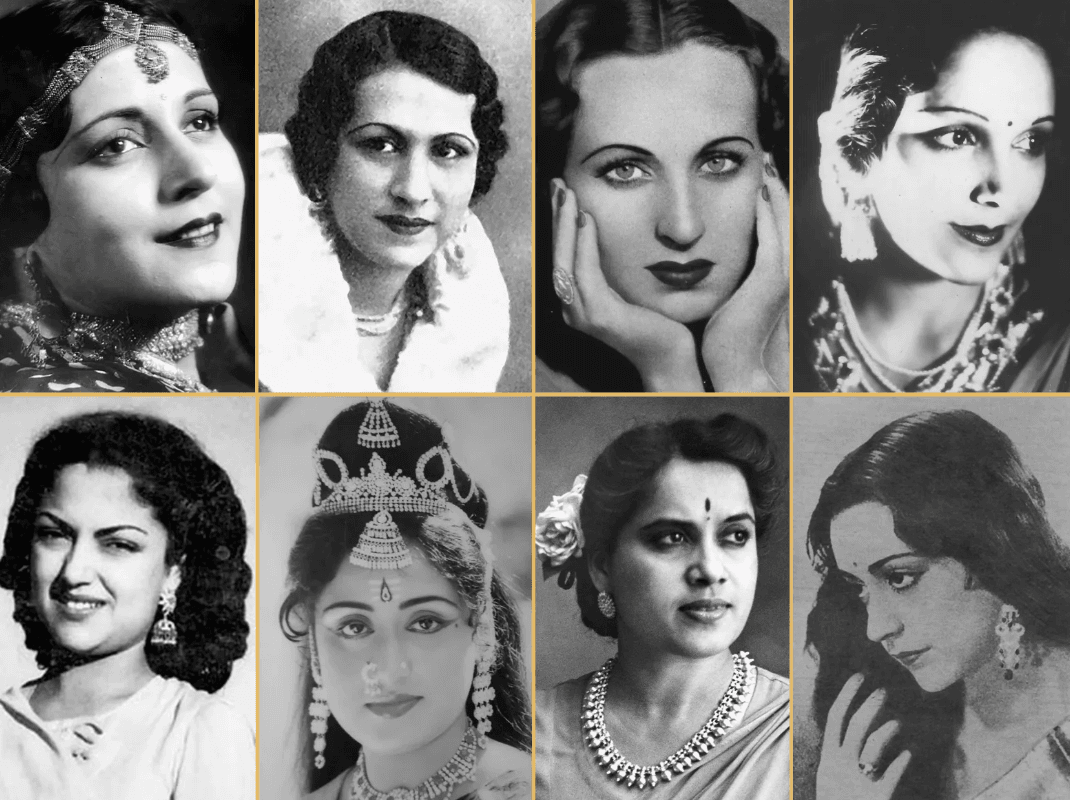

The silent era and the role of Anglo-Indian actresses

But there was still a lull of women in Indian cinema because of the societal pressure that followed stardom. The alternative was to find women from the communities who either were not part of the traditional Indian society or women who already had a presence in the Indian theatre. While filmmakers like Himanshu Rai used European women draped in Indian clothes for their initial films, the Parsi theatre owners brought Anglo-Indian and Parsi women with Sanskritised names like Sulochna, Pramila, Nadia etc.

Sulochna and Pramila became the centre point of Hindi cinema in the 20’s. So immense was their popularity that it was said that Sulochna earned more than the governor of Bombay at that time. Her important films included Typist Girl (1927) and Wildcat of Bombay (1927), the latter having the distinction of being the first film where the actress played eight different roles.

There were many advantages in casting these actresses for such roles. Firstly this was the era of silent films wherein films didn’t have sound and thus these actresses were not required to speak dialogues that would expose their anglicised accents. Secondly, their experience of Parsi theatre and exposure to European cinema came in handy to film-making in India. Thirdly, it was easier to picturise erotic scenes on screen with these actresses as compared to the traditional Hindu actresses like Zarina; who are reported to have performed 82 kisses on screen. These women became the pivot of the silent film era.

The Devadasi women and Indian cinema

With the coming of talkies cinema in 1931, a lot of this began to change. Firstly, the actresses with anglicised accents were now out of work, unable to represent the traditional Indian women with conviction. They were now being replaced by women with backgrounds in performing arts. One of the major groups that contributed to Indian cinema during this period belonged to the Gomantak Maratha Samaj. This group had its history rooted in the Devadasi tradition or the temple performers. Before the 20th century, these women were involved in music and dance traditions in the temples. Many of these temple performers of Kalavantin were also involved as mistresses of Brahmin landlords and priests, giving rise to concubines and illegitimate children.

By the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, a wave of social reform movement swept the region of Maharashtra and Goa, and these Kalavantins started leaving their Devadasi roots in search of more respectable professions. Theatre, music and cinema were such avenues where these people could express themselves legitimately. This is a reason why some of the most respectable artists of Indian cinema, both in music and acting come from this tradition. These artists included the Mangeshkar family (Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhonsle, Hridaynath Mangeshkar etc. who trace their roots to the Mangueshi village of Goa, devoted to Lord Mangeshi), the Kolhapure family (Padmini Kolhapure, Pandharinath Kolhapure), Karnataki family (Actress Nanda, Master Vinayak), Shirodhkar family (Namarata Shirodhkar, Shilpa Shirodhkar), Kimi Katkar, Singer Kishori Amonkar etc. The collective contribution of all these artists is immense to the Indian cinema and the offshoots of these groups are still active in the Indian cinema and music industry.

Religion and women in cinema: The role of tawaifs

Similarly, religion was another major determinant of the cinematic oeuvre of female artists. In the initial years, actors and actresses frequently adopted Hindu screen names to be accepted among the masses, which reflects the sensitive communal conditions and the constant need to sound cosmopolitan in Indian cinema. Suraiya Jamal Sheikh became Suraiya, Mahjabeen Bano became Meena Kumari, Begum Mumtaz Jahan Dehlavi became Madhubala and Tabassum Naaz Hashmi became Tabu.

In a similar setting, another tradition which produced a rich harvest of actors and singers in India was the Tawaifs, who were traditionally associated with courtesans in the royal courts but with the steady decline of the courtesan culture in India after the imprisonment of Wajid Ali Shah and the regulatory measures exercised by the British government, the tawaif tradition in India went into a decline. Many of these women took refuge in theatre and cinema in the 20th century. One of the earliest examples of this can be the mother-daughter pair of Mallika Jaan and Gauhar Jaan, the latter being the first recorded artist on the Gramophone company. These women had illustrious careers as performers and they motivated other artists to follow in their footsteps like Begum Akhtar and Jaddan Bai. Begum Akhtar was a singer as well as actress with a long career span being bestowed with the title of Mallika-i-Ghazal. Jaddanbai made her mark as one of the earliest female music directors of the film industry and later on her daughter Nargis Dutt became one of the top actresses of her time

Women behind the camera

But the role of women was not just relegated to actors and singers. Women technicians, though a minority, have made their mark in Indian cinema. As early as 1926 Fatma Begum produced and directed Bulbul-e-Paristan, and became the first female director of Indian cinema. Similarly, P. Bahnumati’s directorial ‘Chandi Rani,’ (1953) was one of the earliest films to release in Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu simultaneously on the same day.

As the women’s movement gained traction in India, highlighting women’s oppression and the struggle for an egalitarian society, some female filmmakers tried to place women from the margins to the centre of their works. A different point of view and a female gaze emphasised female subjectivity. Aparna Sen, Sai Paranjpye, Vijaya Mehta, Aruna Raje, and Kalpana Lajmi made a number of films that were sensitive portrayals of women protagonists in search of social and sexual identity, women firmly located in specific socio-historical contexts. In the 21st century, we find a huge number of female directors in both commercial and parallel arenas. Some of the most significant film directors of the 21st century include Farah Khan, Zoya Akhtar, Reema Kagti, Konkana Sen Sharma, Alankrita Srivastava etc.

All in all, it is difficult to imagine the history of Indian cinema without the contribution of women as they proved to be the edifice on which the pillars of Indian cinema stand. Female actresses, directors, producers, writers, musicians, singers etc all had immense contributions to the development of cinema in its present form. Women were not the participants of cinema; they were the agents and at times the harbinger of cinema in India. Their contribution cannot be discounted nor undermined but needs to be given due credit in the annals of the history of cinema.

References

- Dasgupta, D. & Roy, P. (Eds.). (2021). Film Studies: A Beginner’s Guide. In-Depth Communication

- Cinema Citizens, Indian Memory Project

- Geetha, K. A. (2021). Entrenched Fissures: Caste and Social Differences among the Devadasis. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22(4), 87-96

- Hubel, T. (2012). From Tawa’if to Wife? Making Sense of Bollywood’s Courtesan Genre.

- https://www.indianmemoryproject.com/cinema-citizens/

- Bhrugubanda, U. M. (2020). Travels of the female star in the Indian cinemas of the 1940s and 50s: The career of Bhanumathi. In Industrial Networks and Cinemas of India (pp. 61-76). Routledge India.