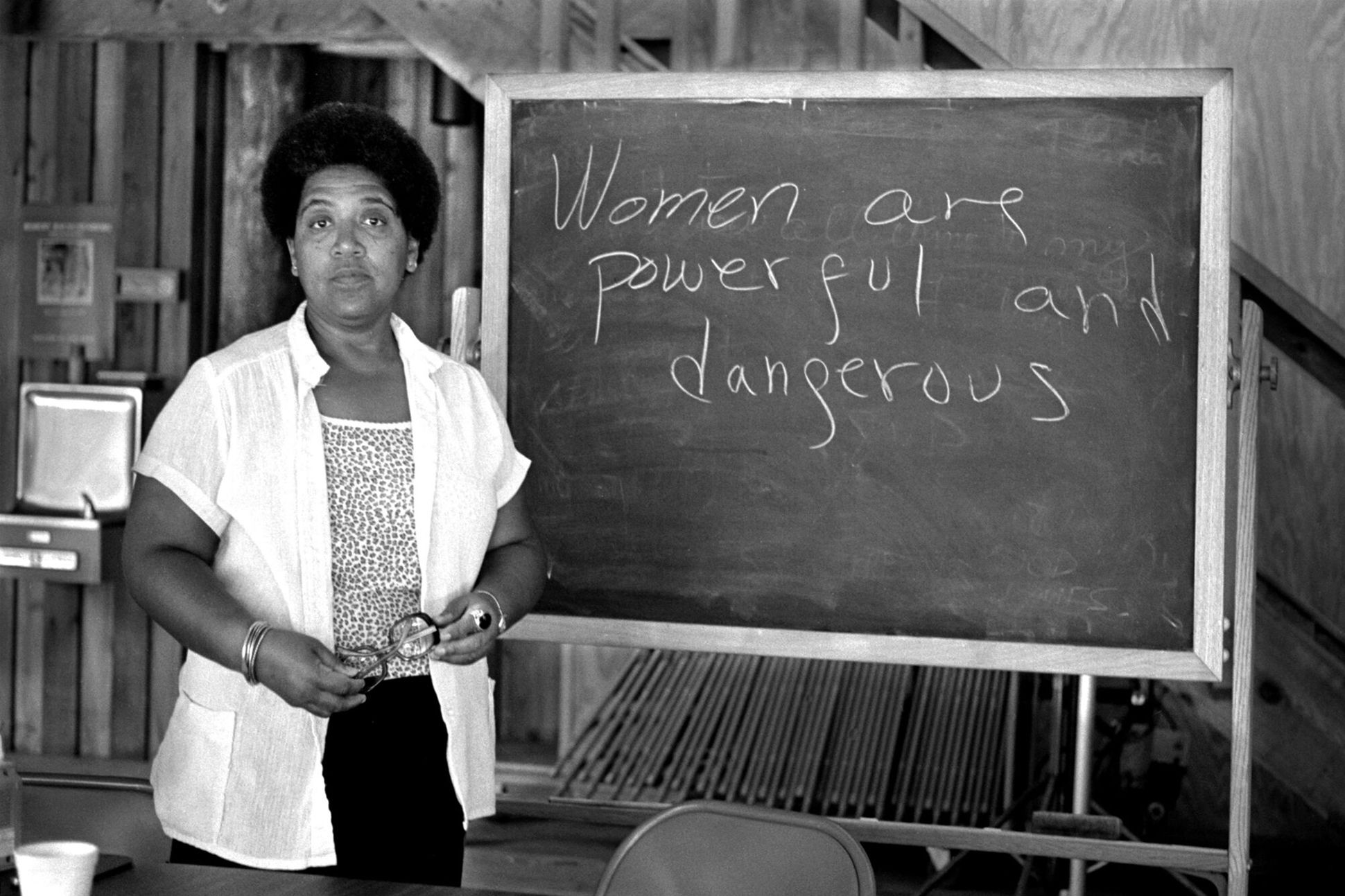

There is a long and tangled history of literature imagining motherhood as either miraculous or monstrous, and very little in between. There are stories of the good mother, the mad mother, the self-sacrificing mother, and the absent one. She is either a silent giver or a loud abandoner, sometimes – paradoxically – both.

What is often left unsaid is how profoundly motherhood dismantles the self. Not in the poetic, selfless, halo-of-light way that makes it to Instagram posts, but in the deeply intimate, often terrifying, psychological way that fiction is uniquely able to capture – and that society is equally skilled at glossing over. We celebrate mothers as life-givers, caregivers, and multi-tasking miracle workers, but only within the narrow lanes of sacrificial virtue. Motherhood can, of course, be a source of joy, connection and profound transformation, but the painted picture may not always be positive. Ask any mother what happened in her mind after giving birth, and you might hear about something more untethered. Something that is perhaps a little too unsightly for Instagram captions.

Psychotherapist Naomi Stadlen, in “What Mothers Do – Especially When it Looks Like Nothing,” points to a quiet contradiction at the heart of early motherhood: mothers spend their days listening to their children, attuning themselves constantly to another’s needs, but often go unheard themselves. But where society and culture flinch away, literature leans in. Novels and memoirs alike have charted the intricacies of motherhood – not just the visible acts of care but a mother’s internal struggles. These are not sentimental odes to motherhood. They are sharp, often disquieting portraits that ask: what happens to a woman’s self when it is reorganised around the needs of another human?

The self that was: Into early motherhood

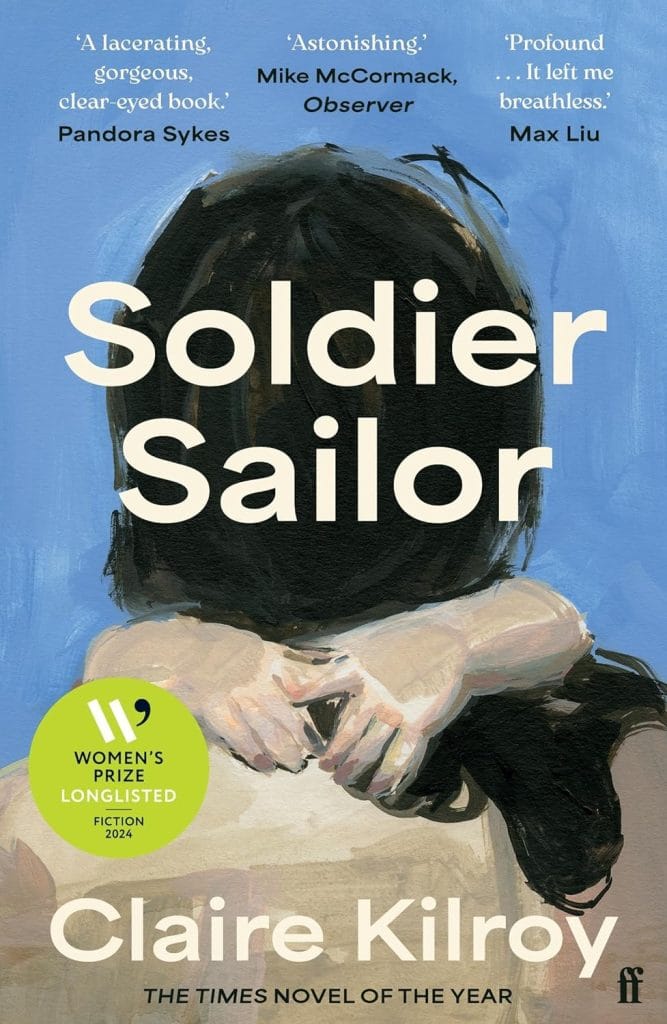

Claire Kilroy’s searing 2023 novel about early motherhood, Soldier Sailor, is not the first to write about maternal unravelling, but it is among the few that make it impossible to look away. The erasure of the self is central to the book. The unnamed narrator – known only as Sailor’s mother or ‘Soldier,’ – is not heroic, noble, or wise. She is angry, disoriented, and cracked open by her proximity to someone she loves so much it nearly kills her. Her chosen identity, ‘Sailor’s mother,’ reads at once as an act of devotion and a chilling premonition: she is already vanishing. She doesn’t know who she is anymore, but she remembers who she was – before the cracked nipples, the constant crying (both his and hers), and the deep sense of entrapment that no one warned her about. Her descent into what looks like postpartum anxiety, if not postpartum psychosis, is not couched in technical or diagnostic language.

Instead, it is rendered in sentences that spiral and loop, much like her thoughts: “I am tired. I am lonely. I have found myself mired in resentment in this new life, become a person I don’t wish to be, feeling constant guilt for not feeling constant gratitude for the blessing that is my child. I do feel constant gratitude: I adore my child. But I am tired. I am lonely. I am lost.” The novel’s fragmented narrative structure mirrors her cognitive state – disjointed, foggy, panicked – and this structural approach becomes its feminist intervention. Kilroy doesn’t offer redemption. She offers reality. The mental health crisis the protagonist experiences is not abnormal – it is, terrifyingly, ordinary. This ordinary despair echoes, too, in Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, where a woman’s identity fractures quietly over the course of the book, though the trigger is less early motherhood than the cumulative weight of care, a dissolving marriage, and unmet creative ambition.

Offill’s narrator begins as a writer with fierce artistic ambitions – someone who once believed she could become an ‘art monster.’ But somewhere along the journey, the novel’s first-person ‘I’ gives way to a distant ‘wife.’ “My plan was to never get married”, the narrator reflects early on. From then on, it is not a traditional narrative arc – it is a depiction of erosion, a byproduct of being expected to nurture another, work, cook, forgive, smile – all at once. It is within these lines where literature performs its quiet feminist labour. These are not stories of bad mothers; they are stories of honest ones, navigating roles that were never designed with their inner lives in mind.

The unromantic mother

While fiction captures the atmospheric horror of early motherhood, memoirs like Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother show us how deeply embedded this unravelling is in reality. Written in crisp, often acerbic prose, over the length of several short essays, Cusk’s account refuses to romanticise new motherhood. As she writes, “Motherhood, for me, was a sort of compound fenced off from the rest of the world.” Her book explores the daily humiliations, identity shifts, and psychological disorientation of early childcare. It doesn’t offer a resolution or a lesson; instead, it testifies to how thoroughly motherhood reorganises a woman’s inner self – and how little space there is, culturally or structurally, to voice that disarray.

If Cusk’s memoir forces us to confront the psychological weight of motherhood from the inside, there are other texts that widen the lens, examining how the legacies of motherhood stretch across generations.

Bad daughters, worse mothers

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi flips the narrative. Here, we see the long-term psychological fallout of negligent parenting. Antara, the daughter of a woman who refused ‘traditional,’ motherhood, now bears the burden of care. The novel doesn’t excuse maternal failure – it stares directly at it, unflinching.

The complexity of intergenerational motherhood – of loving and resenting, of remembering and misremembering – threads through Doshi’s narrative like mould: visible only when you look closely, but always growing. While the novel never centres on maternal mental health explicitly, it remains deeply haunted by it. The mother’s decline becomes the daughter’s inheritance, not just biologically but also psychically. The result is not redemption but a kind of bitter recognition: that women who reject caregiving are punished, and those who don’t are consumed by it.

What unites these works is their refusal to perform the good mother or to seek forgiveness for being otherwise. They reject the trope of motherhood as redemptive and instead dwell in its mess – the sleeplessness, the confusion, the boredom, the dread. In doing so, they resist the cultural myth that suffering is sacred or that sacrifice should be aestheticised to fit into the ‘Perfect Mother,’ narrative.

The invisible man

If literature has spent decades contorting itself to examine every narrative surrounding motherhood, from the saintly to the shattering, fatherhood has inexplicably stayed unchanging, heroic even. Fathers float in and out of the story like benevolent ghosts in many texts that depict maternal anguish: they are present but unaccountable. The father figure is mostly absent from Soldier Sailor, and when he does appear in the narrative, it is both infuriating and predictable that he is unable to comprehend the enormity of her experience. While she fractures under pressure, he remains complete, intact. This isn’t just a literary device; it is a cultural pattern.

As Cusk writes in her memoir, “…after a child is born the lives of its mother and father diverge, so that where before they were living in a state of some equality, now they exist in a sort of feudal relation to each other.” Fathers are rarely asked to describe how parenting changed them or to recount the psychological effects of early caregiving. Their silence is inherent and assumed normal.

Meanwhile, mothers are not only expected to describe and defend their silence but also to aestheticise their pain to a certain extent. This imbalance is significant in that it isolates a mother’s experience and reinforces gender norms, transforming what is essentially an institutional deficit into something perceived as profoundly personal.

When a mother struggles, society tends to look for personal shortcomings: her attitude towards motherhood, her readiness, and her mental health. Rarely does the conversation pivot to question why caregiving is so structurally unsupported or why paternal absence is normalised. By rendering fathers invisible and mothers individually accountable, culture ensures that maternal breakdowns remain private tragedies rather than collective critiques. Literature, on the other hand, allows the burden to shift back to where it belongs: on systems, and not just selves.

The honest mother

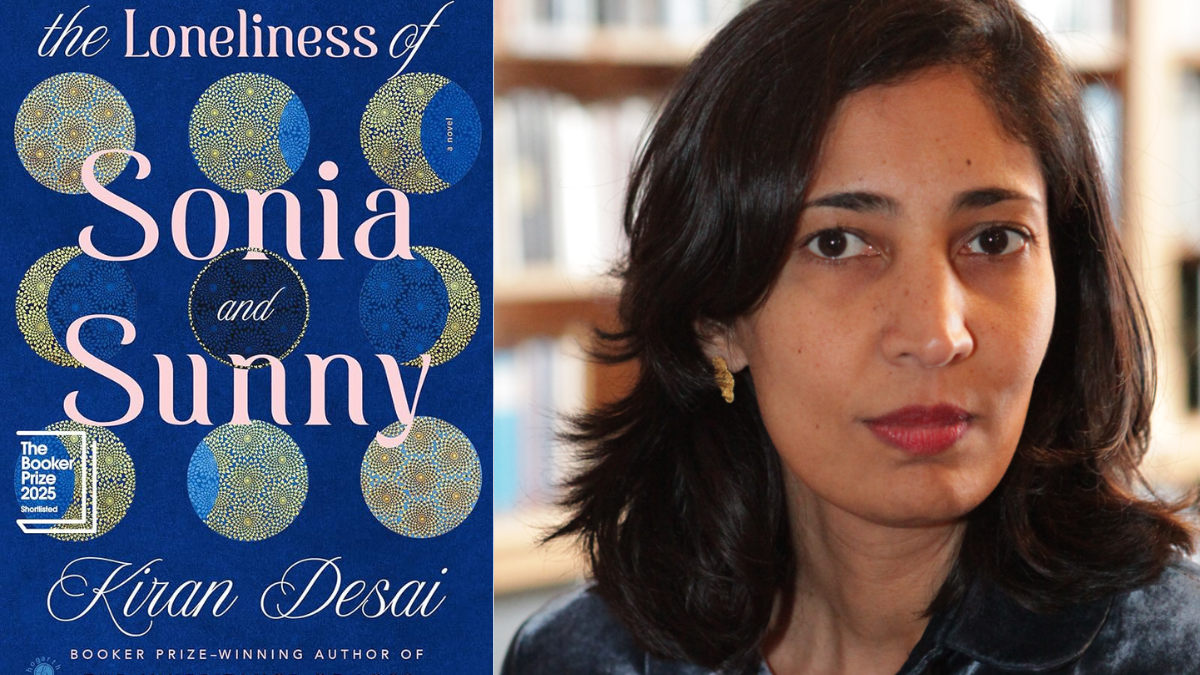

As Eliane Glaser writes in The Guardian, “Realism is a political act: it builds solidarity and better conditions.” The power of books like Soldier Sailor, Dept. of Speculation, Burnt Sugar, and A Life’s Work lies in their refusal to idealise.

Instead, they give voice to the real thoughts women – and mothers – are often discouraged from admitting. That a mother might miss her old life, as Soldier does. That she might, at times, resent the very people she loves most. That caregiving, far from being purely virtuous or redemptive, can also feel like annihilation – a truth captured in the narrator’s quiet breakdown in Dept. of Speculation. These narratives make it clear: maternal mental health isn’t an aside. It is central.

Crucially, they are not just feminist in content but in form. They resist neat narrative arcs, deny tidy resolutions, and refuse to package motherhood in sentimentality. Fragmented, restless, unresolved – their very structure mirrors the cognitive and emotional disarray of mothering. They do not seek redemption; they seek recognition. And in doing so, they offer readers a quiet provocation: what if the opposite of the ‘perfect mother,’ isn’t the ‘bad,’ mother but the honest one?