Is violence against marginalised women so normalised that it does not shock the society? Or is rape culture so deeply entrenched that some lives are simply not seen as worthy of justice? These questions haunt us when one looks at the lack of response to recent incidents of gendered violence and killings. On the night of May 23, 2025, a 45-year-old tribal woman from the Kurku tribe in Madhya Pradesh’s Khandwa district was brutally gang-raped by two men from her own community. She bled to death by noon on May 24, 2025. The absence of social media outrage, solidarity posts, or even any headline shows a troubling indifference. How many more women must become just numbers before we pause and listen? When Dalit or Adivasi women are raped, what keeps our collective outrage stifled? When will we discard the frameworks of selective outrage that this patriarchal society instills in us?

Rape is a horrific crime regardless of the victim’s identity and cannot be defined solely by its severity or extremity. But in practice, not all rape victims are remembered equally. Public attention often gathers around those involving urban, suburban, upper-caste, or middle-class individuals. When injuries are visibly brutal or described in graphic detail, they tend to stir a stronger reaction. This creates a dangerous hierarchy of suffering, where only the most extreme cases are mourned.

A hierarchy of suffering

This layered neglect cannot simply be understood through gender. In her essay Gendering Caste, Uma Chakravarti writes that caste is not only about hierarchy but also about controlling a woman’s sexuality. For tribal women, this control takes a different form. While upper-caste purity codes may not apply in the same way, tribal women are instead made vulnerable through systemic neglect, erasure, and a lack of justice. They do not fit neatly into Savarna feminist frameworks or mainstream legal imaginations. Sharmila Rege’s concept of a “Dalit feminist standpoint” helps frame violence not just as an event but as a structure. She argues that sexual violence is shaped by caste and patriarchal ideologies that seek to punish women from oppressed communities simply for being visible and mobile.

Not all rape victims are remembered equally. Public attention often gathers around those involving urban, suburban, upper-caste, or middle-class individuals. When injuries are visibly brutal or described in graphic detail, they tend to stir a stronger reaction.

The tribal woman in Khandwa had gone to a wedding, and for many, that alone was reason enough to violate her. Gopal Guru, in Dalit Women Talk Differently, reminds us that silence is a socially produced act. The way people, the media, and even social media stayed quiet about the Khandwa case exemplifies what Guru calls “graded indignation”. This means that not all rape cases are treated equally. When the survivor is Adivasi, Dalit, or from other marginalized communities, the violence is often ignored or accepted without outrage. Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality provides a framework to understand why certain survivors disappear from public memory. The Khandwa victim was not only a woman but also a tribal, marked by overlapping systems of vulnerability as she was also a tribal woman in a casteist society.

While some incidents of sexual violence against Dalit women, like the Hathras case, have briefly entered public conversation, the suffering of Adivasi women often remains completely ignored. The gangrape and death of the Adivasi woman in Khandwa did not lead to public outrage. This silence reflects how mainstream society often chooses which lives and bodies are worth grieving.

Scholars like Sharmila Rege and Gopal Guru have shown how the justice system is shaped by upper-caste interests. It only reacts when violence touches the spaces of urban privilege. Even the limited support that Dalit women sometimes receive is not extended to Adivasi women. Their communities are already seen as distant or outside the political imagination, and when atrocities against them are met with such silence, it acts as a step toward further marginalization.

The pattern of erasure

In the months following the Khandwa incident, similar cases involving Adivasi women have continued to surface. In Odisha’s Jajpur district, a 32-year-old tribal woman was gangraped while herding goats in a forest on July 1, 2025. Just two weeks earlier, in Keonjhar district, a 17-year-old Adivasi girl was raped and later found hanging from a tree. A few weeks prior to the Khandwa rape case, a tribal woman was reportedly sexually assaulted and murdered near Water Works Road in Nishat, Srinagar. Although arrests were made and some local outrage emerged, the case did not enter national feminist discourse.

The Brahminical nature of state institutions shapes how violence is understood, reported, and redressed. Rape, in these cases, is gendered as well as shaped by caste and embedded within a social structure that normalizes violence against the marginalized while denying it legal recognition.

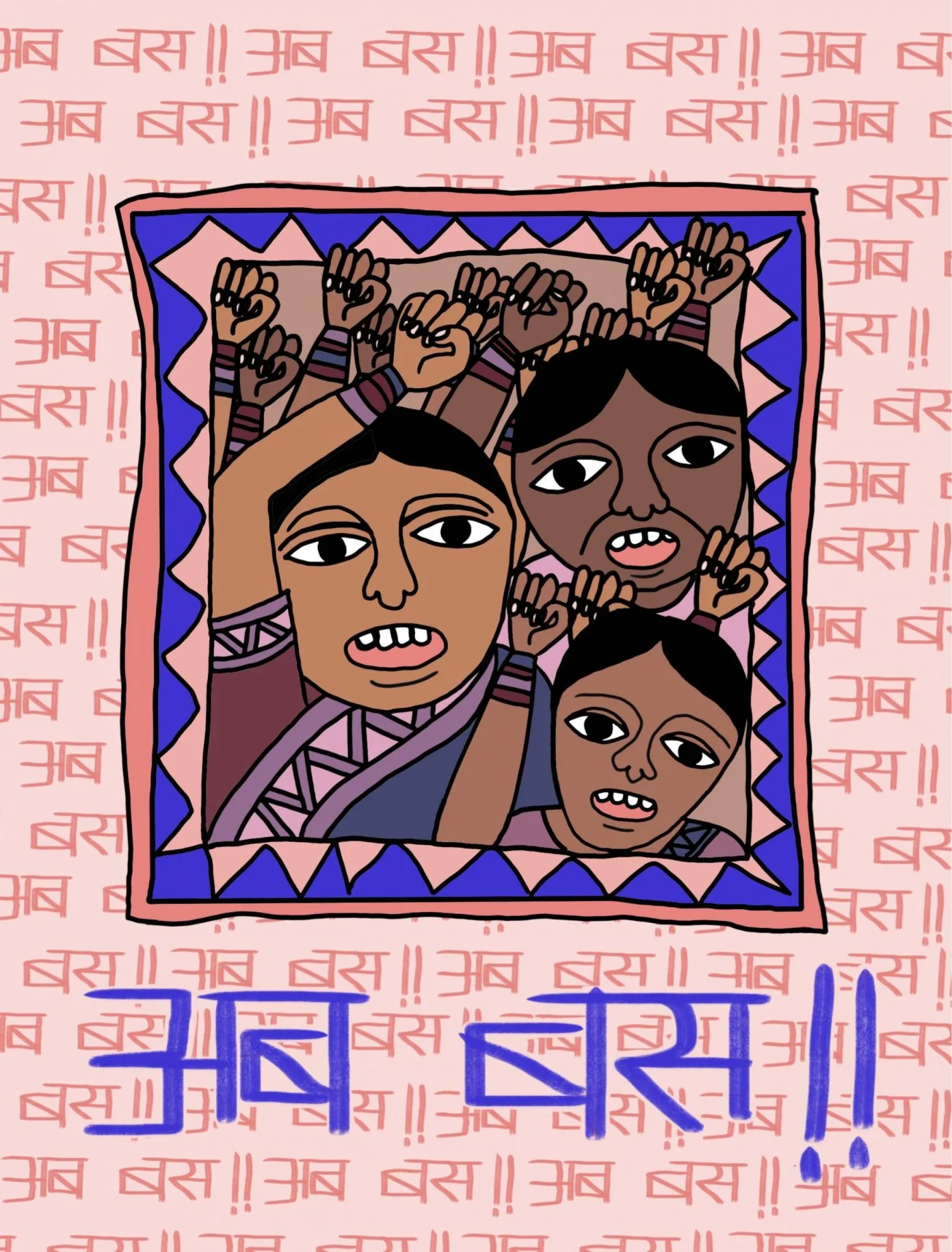

While upper-caste liberals and feminists often raise their voices, they rarely confront the caste realities underpinning such violence. As critiques from Dalit and Adivasi activists have long asserted, feminist and progressive spaces remain deeply shaped by Brahminical privilege. The populist slogan “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” feels empty when Dalit and Adivasi women are neither protected nor remembered. Unless society understands that caste is deeply connected to gender-based violence, both the state and mainstream feminism will keep ignoring the voices of marginalized women.

Rethinking justice and feminist response

The response to these cases warrants scrutiny. Why did they not circulate like the RG Kar or Nirbhaya cases? Is outrage reserved for victims society can identify with or relate to? Are tribal women too far or too different to evoke public grief? Across India, multiple Adivasi women have been raped in recent months, many of them minors, some of them murdered, and yet, the outrage is muted, if present at all. It points to how perspectives of the dominant castes shape what is collectively considered tragic, and rape is seen as horrific only when it threatens upper-caste ideas of respectability or safety.

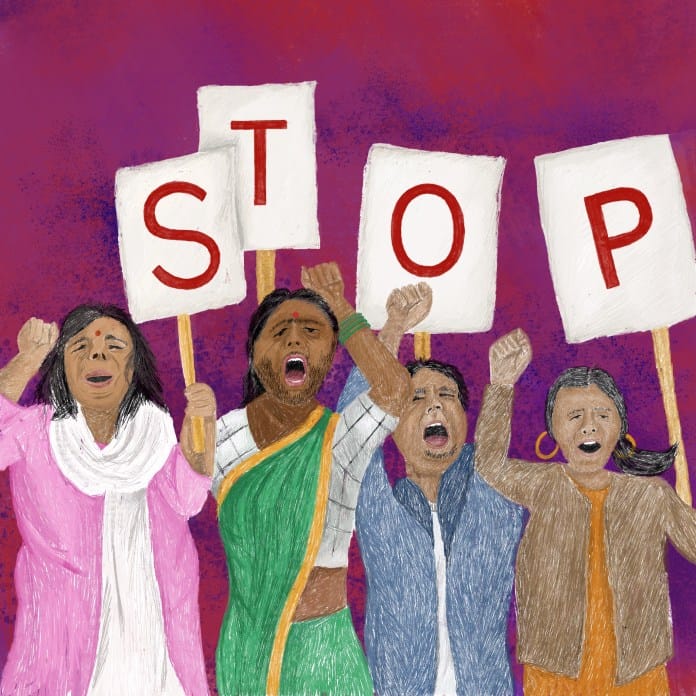

Feminists, especially those in academic and activist circles, must treat news about tribal regions as central to understanding gendered violence in India, not as footnotes. Legal reforms are necessary, but they are not enough, and institutional justice must be accompanied by cultural justice. Society must talk about and remember the names that are not trending, and question the silence that surrounds them.

The Brahminical nature of state institutions shapes how violence is understood, reported, and redressed. Rape, in these cases, is gendered as well as shaped by caste and embedded within a social structure that normalizes violence against the marginalized while denying it legal recognition. Punitive justice systems, like the death penalty in the Nirbhaya case, cannot comprehend this layered violence.

Dalit feminists have rightly questioned whether existing laws made within Savarna frameworks can ever fully deliver justice to Dalit and tribal women. What happens when justice itself is mediated through caste and class? In a country where women are repeatedly told that their victimhood must fit a box to be acknowledged, the death of a 45-year-old tribal woman in Khandwa reminds us of the cost of invisibility. Let society not wait for another death to remember her.