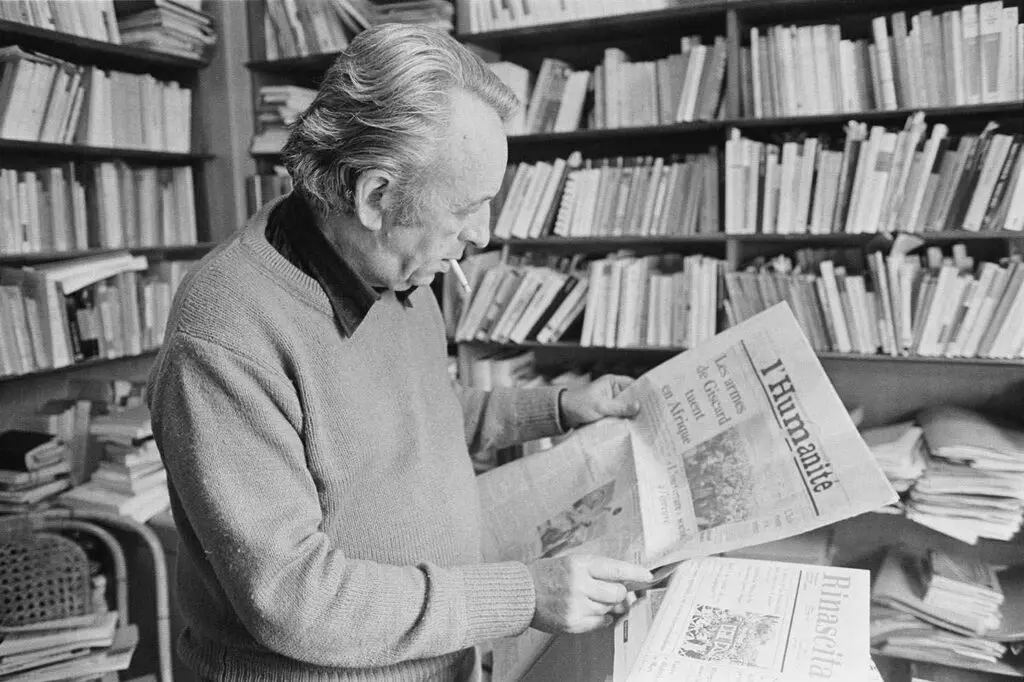

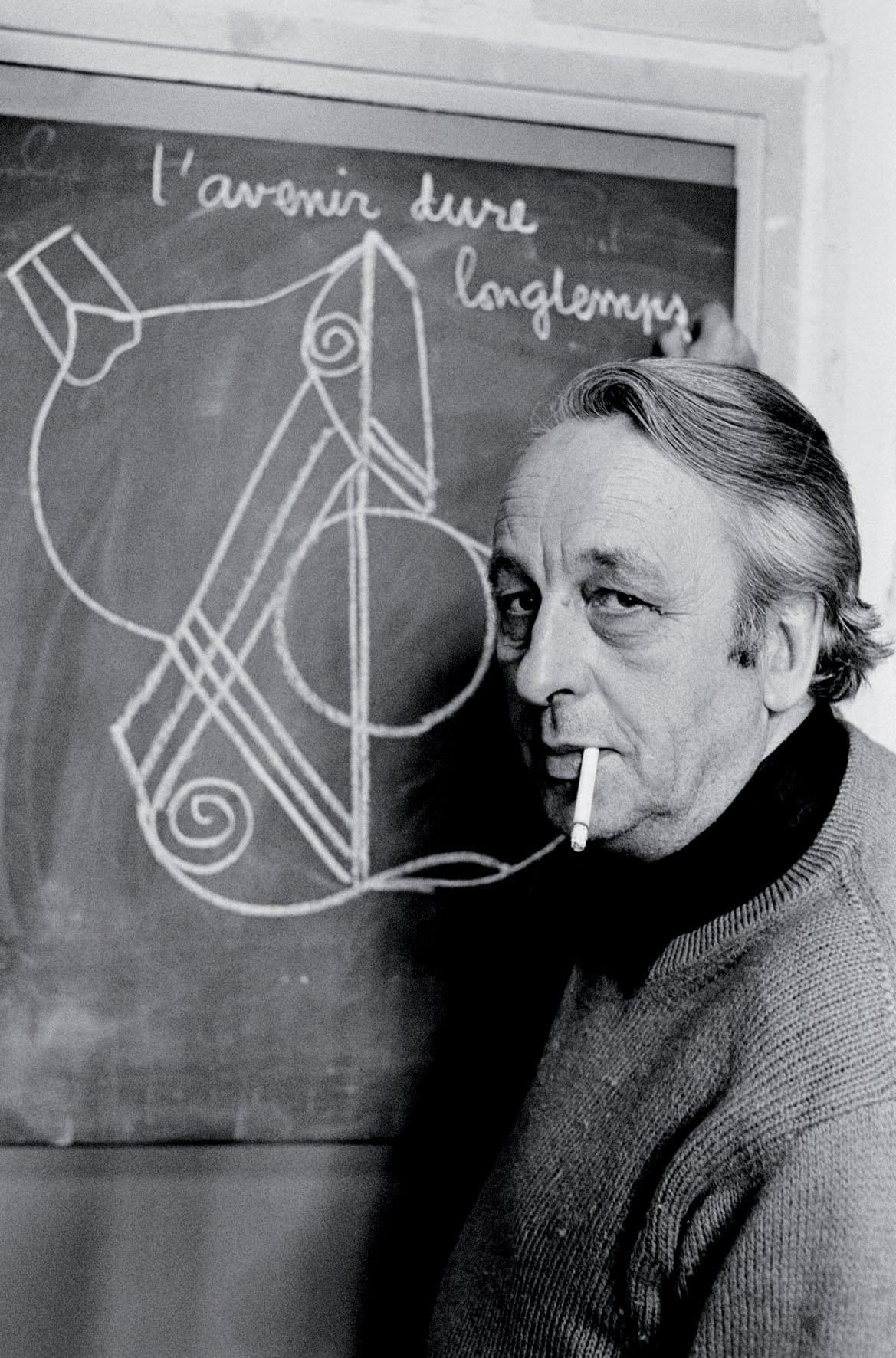

The French Marxist Louis Althusser, in a 1970 essay titled “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an investigation),” identified the central role played by ideology in everyday discourse. Implied in the way of life, ideology, thus, is more than a set of beliefs about the world. It encompasses material practices within specific institutions, leading to subject formation and the reproduction of social relationships, thereby shaping and policing our behaviour and boundaries. In this text, Althusser introduced the concept of “interpellation” as well.

Althusser also underscores that the ideological state apparatuses, such as the family, religion, and culture, combined with the repressive state apparatuses, such as the police and the army, serve to spread the dominant ideology in society. In the process, the constructed ideologies, embodied in such apparatuses, cause the internalisation of identities, which become the sole marker of individuality in social interactions. Individuals thereby transform from being themselves into social actors controlled by the agency of the dominant social institutions. Time and again, Althusser’s concept of “interpellation” has been neatly folded along the creases to fit the feminist ideological discourse. Ideology, thus, becomes fluid, reinforcing social behaviors and role perception in society.

Interpellation and gendered behaviours: a feminist theoretical perspective

Judith Butler’s concept of performativity is closely linked to Althusser’s understanding of interpellation. Butler, in her work, underscores the impact of “hailing” created by ideological forces in society, within a gendered framework, that leads to the formation of subjects and the roles assigned to us. Defined as the performative materialisation of the social environment, her work is instrumental to our understanding of how gender roles are distributed, perceived, and followed in society. This entanglement of performative materialisation with social norms and values is closely tied to guilt and compulsion acting on an individual. Gender, for Butler, is produced through repeated ideological acts of interpellation.

Simone de Beauvoir, similarly known for her trailblazing work in feminist philosophy, most notably for The Second Sex, is a catalyst for challenging women’s situations with a distinguished feminist perspective in society. Her emphasis is on escaping patriarchal gendered polarisation by deepening a form of singularity that transcends the traditional gendered boxes we are cramped into. While the ideas posited might seem ambiguous, they center on the rejection of the patriarchal notions of femininity by the rejection of all externally imposed identities, thereby interpellating women as creative constructors of their singular subjectivity, with a focus on autonomy.

Bell Hooks’ works too imply the idea of inverting the power hierarchies and interpellation of identities, including the need to make the whole ideological construct more encompassing, comprising an end to sexual oppression rooted in racism, classism, and imperialism. These, according to her, are identities of domination, consigning to individuals the way they are “hailed” in society. The classic police officer trope to understand this “hailing” can also be applied to the process where gender roles are assigned automatically based on an individual’s sex since birth.

Policing the self: patriarchal sites, control, and identity

Althusser’s concept of interpellation, while being central to sociological studies, has also established itself in the understanding of how gender is constructed symbolically in culture. All patriarchal institutions, whether dating, motherhood, or sexuality, work on an implicit consignment of individual identities, which become internalised, thereby reinforcing specific gendered subject positions and patriarchal structures.

All patriarchal institutions, whether dating, motherhood, or sexuality, work on an implicit consignment of individual identities, which become internalised, thereby reinforcing specific gendered subject positions and patriarchal structures.

The semiotics of dating traditionally relies on the understanding that men approach women with no space for queer romantic experiences, thus converting gender into a social construct that “hails” individuals to conform to specific societal expectations. Additionally, the media, as the conduit of our understanding of how society works, reinforces these norms from a young age via exposure to books, films, and news, shaping our understanding of how dating works from a primarily masculine lens.

The way sexual politics works, on a similar note, interpellates men as seekers of pleasure with certain desires. The role of women is restricted to providing sexual pleasure with certain implicit expectations related to performance in bed. Sexuality is understood from a patriarchal lens, primarily as an act between a biological man and woman, marking its rigid boundaries. Ambiguous heterosexual experiences are very often treated as a form of domination, distinct from both coercion and productive power. Heterosexual domination, as a form of Althusserian interpellation enables us to see the power in question and how it is rejected. The codification of heterosexual intercourse is also closely related to the argument that posits men as perpetrators and women as “morally superior victims” by male researchers. The creative and transformative political force of queer experiences and their affirmative rejection is scarcely paid any attention to.

Motherhood can be understood as the epicenter of the gendered application of Althusser’s interpellation. The process of becoming a mother interpellates feminine identity to the role of a mother through societal and cultural expectations and norms. The idea of motherhood, being a selfless and divine entity solely invested in children’s well-being while sacrificing individual dreams, reflects the concept. Women, thereby, easily “hail” themselves as mothers, resigning to the pressure to conform to these expectations voluntarily because of the social architecture. Certain parenting practices embed these ideological expectations, associated with feelings of guilt and compulsion, also identified by Beauvoir.

In the contemporary global landscape, cinema, as well, changes from an instrument of entertainment to a hegemonic cultural apparatus configuring collective imaginaries, mediating dominant ideologies, and authorising specific etymologies of truth and violence.

In the contemporary global landscape, cinema, as well, changes from an instrument of entertainment to a hegemonic cultural apparatus configuring collective imaginaries, mediating dominant ideologies, and authorising specific etymologies of truth and violence. Besides reflecting societal norms, filmic representations operate performatively, reifying ideological constructs. The gendered gaze and representational strategies either serve to hyper-visualise, fetishise, or entirely erase the marginalised identities, connecting the politics of being seen with the politics of knowing and being.

These institutions don’t merely serve as patriarchal sites, but they become active agents of the process of interpellation. The process is never totality in itself. While it is an approach that assigns individual roles into definite total categories, never fluid, it’s an approach to understand how ideology shapes and constructs our experiences even before we realise it. Implicit in the everyday power dynamics, to be interpellated is to refuse, to conform, to resist, to adopt.

The process isn’t entirely freedom in itself. It is also the ability to reframe or restructure the structures shaping ideology and the understanding of the same. At the end, we might be hailed as a wife, a mother, a submissive partner but to be chosen to become something more is always on us.

References:

- Althusser, L. (1970) Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation). [Essay].

- Callari, A. & Ruccio, D.F. (2017) ‘Subjectivity, interpellation, and reproduction of social relations: Althusser, Butler, and the subject of ideology’, Rethinking Marxism, 29(3), pp. 387–407. doi:10.1080/08935696.2017.1358498.

- The Hindu (2017) ‘What is interpellation in political philosophy?’, The Hindu, 20 April. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/what-is-interpellation-in-political-philosophy/article18149228.ece (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- McNay, L. (2022) ‘Subject formation and feminist theory’, in The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/41973/chapter-abstract/355256367 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- Thakur, R. (2023) ‘The Celluloid State: Gender, ideological interpellation and epistemic violence in contemporary Indian cinema’, ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393944822 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- Cocks, H. (2017) ‘Dworkin’s subjects: Interpellation and the politics of heterosexuality’, ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312959783 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- Mills, C. (2018) ‘Easier than saying no: Domination, interpellation, and the puzzle of acquiescence’, Hypatia, 33(4), pp. 700–717. doi:10.1111/hypa.12425.

- Hooks, B. (2000) Feminist theory: From margin to center. 2nd edn. Boston: South End Press. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2207&context=jiws (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

- McGlotten, S. (2009) ‘Subjected subjects: On Judith Butler’s paradox of interpellation’, Hypatia, 24(4), pp. 94–112. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2009.01061.x.

About the author(s)

Nausheen is currently an undergraduate student pursuing journalism at Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Delhi University. With a keen interest in feminism, geopolitics, and social issues, her passions lie in research, writing, and public speaking. In her free time, she enjoys listening to music, sipping coffee, and playing chess.