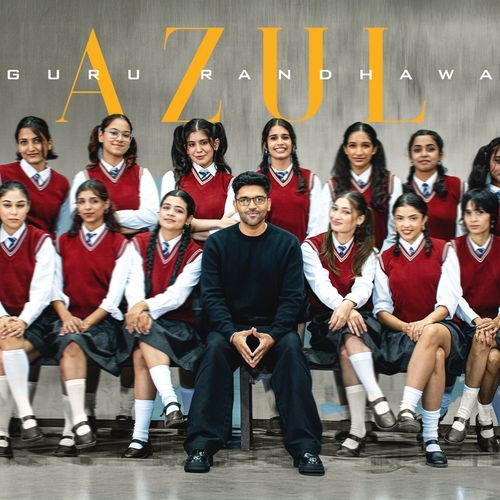

The first time I watched Guru Randhawa’s new video, ‘Azul’, I felt deeply unsettled. Not because of the melody; that’s forgettable. But because halfway through I kept picturing my younger sister’s school uniform hanging neatly in her closet, and I couldn’t shake the thought: Is this how pop culture teaches an entire generation to see schoolgirls? ‘Azul’ opens with Randhawa entering an all-girls school, where minor girls are in their school uniforms. Within seconds, he’s staring at the girls in school uniforms. Then, one actress playing a schoolgirl enters, and he stares at her with the kind of lingering gaze that would make any parent’s skin crawl. The video doesn’t try to hide what’s happening – we’re watching him gaze at her, the camera capturing his obvious sexual interest in a character meant to be a minor. She starts dancing wearing her uniform and is portrayed in a highly sexualised way, which will promote harmful notions about schoolgirls among a heavily male audience, especially young boys. Then comes the transformation. Eventually, her school uniform disappears, replaced by casual clothes as she becomes the video’s main lead, now joined by other performers dancing alongside her.

The lyrics are even more disturbing, systematically comparing these young women in school uniforms to premium alcohol brands, objectifying them as consumable commodities. Randhawa spends his entire video equating them to Hennessy, Teremana Tequila, and rare vintage bottles. He presents himself as the adult authority in glasses, behind the camera, evaluating and desiring these bottles.

The lyrics are even more disturbing, which systematically compare these young women in school uniforms to premium alcohol brands, objectifying them as consumable commodities.

He’s 34 years old. The girls are presented as high school students. There’s no ambiguity here, no artistic interpretation to debate. It’s a music video that openly sexualises minor schoolgirls and sends harmful messages to society. And somehow, this got made, distributed, and watched by nearly 100 million people without anyone in the production chain stopping to ask if it crossed a line.

Those 100 million views didn’t happen by accident. They represent an industry that knows exactly what it’s selling and an audience that’s buying it.

Children and school girls exposed to violence: Numbers don’t lie

Can India really afford this kind of content when our children, minors and school-age girls are already heavily exposed to violence and abuse? The statistics alone should terrify us in this country. According to the NCRB Crime in India 2022 report, India registered 162,449 cases of crimes against children in 2022; that’s nearly 450 cases every single day and an 8.7% increase from 2021.

Here’s what should terrify us: the sharp rise in sexual violence against children. A FairPlanet analysis reveals that sexual violence surged by 96% between 2016 and 2022. In 2022 alone, nearly 39,000 children reported experiencing rape or penetrative assault.

That’s more than 100 children sexually assaulted every day, an average of more than four reports every single hour. How do we even process numbers like that?

This July alone proved how real this crisis is: a science teacher in Tamil Nadu was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting at least 21 girls during school hours. That same month, a Mumbai English teacher was charged with repeatedly raping her 16-year-old student over an entire year, often drugging the child with anti-anxiety medication to facilitate the abuse.

Videos like this validate the most problematic attitudes. Boys learn that staring at girls in uniforms is attractive, not predatory.

And in the middle of this nightmare, we’re producing music videos that teach an entire generation that schoolgirls exist for the pleasure of the adult male gaze. With documented cases of authority figures exploiting students, the last thing we need is pop culture that normalises this exact dynamic.

Fetishising school girls: normalising the abnormal

When millions of young Indians consume videos that normalise the sexualisation of schoolgirls, their understanding of acceptable behaviour fundamentally shifts. Videos like this validate the most problematic attitudes already lurking in our society, giving them mainstream legitimacy. They make the abnormal seem normal, the criminal seem acceptable.

The psychological impact is immediate and lasting. Boys learn that staring at girls in uniforms is attractive, not predatory. Girls absorb the message that being reduced to liquor bottles is flattering, not dehumanising. School uniforms, symbols that should represent education and potential, become fetishised props.

We have seen the comments. Teenage boys are defending Randhawa, saying critics are “overreacting”. Girls joking about wanting to be in the video. This is how it starts.

Girls absorb the message that being reduced to liquor bottles is flattering, not dehumanising. School uniforms, symbols that should represent education and potential, become fetishised props. Teenage boys are defending Randhawa, saying critics are “overreacting”. Girls joking about wanting to be in the video. This is how it starts.

Research confirms what we’re witnessing. The 2024 Humanium report on media sexualisation warns that such content fosters a culture where girls and women are valued primarily for sexual appeal. More troubling, it normalises unhealthy power dynamics between older men and younger women, fundamentally shaping how an entire generation understands gender and sexuality.

When laws fall short

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, enacted in 2012, was designed to shield minors from sexual exploitation in all its forms. The act criminalises watching or collecting pornographic content involving children and makes encouraging child sexual abuse an offence. The law even covers situations where adults are portrayed as children, with Section 2(1)(da) defining child pornography as “any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a child” regardless of whether real children are involved.

Everything depends on that word “explicit”. Unless the content depicts actual sexual activity, it escapes legal consequences. Music videos like these exploit this loophole perfectly, pushing boundaries while staying below the legal threshold.

Other democracies are beginning to acknowledge this gap. In Australia, the AANA Code of Ethics and the Children’s Advertising Code impose strict restrictions on the sexualisation of minors in media and marketing, banning sexual appeal, sexual imagery, or any suggestion that children are sexual beings, particularly in content aimed at children.

We can’t afford more stereotyping content that perpetuates harmful predatory ideas. Parliament must immediately consider tackling the POCSO Act’s loopholes that allow such forms of suggestive sexualisation. The law should take into account portrayals of minors in sexual contexts, explicit or suggestive, bringing India’s child protection framework into the digital age.

But we need more than legal reform. Platforms must stop promoting content that objectifies minors just because it drives engagement. Advertisers should pull funding from any project that reduces minor girls to consumable objects. Parents need to demand better from an industry that’s actively teaching their children dangerous lessons about consent and power.

The choice before us is clear: we can continue rewarding a system that profits from every exploitative view. At the same time, creators monetise legal grey zones at minor girls’ expense, or we can build a country where creative expression thrives without sacrificing our girls’ safety and dignity. Every day we delay action is another day we tell India’s schoolgirls their dignity is negotiable and their exploitation profitable.

About the author(s)

Mehvish is a law graduate from university of Kashmir and currently presides over SAAYA, an NGO serving Kashmir's underprivileged communities.

Sad state of affairs.

Loved the article