Delhi is a city that has no shortage of culture and people willing to immerse themselves in it. Every day and night, it brims with art exhibitions, dance and music recitals, theatre performances and more. People wait in line outside the auditoriums of Mandi House before a play begins, huddle up around scholars leading heritage walks, and sit on stairs to keenly listen to lectures when all the seats are occupied. These events are hosted in auditoriums, art galleries, museums, and universities (and now even bars) scattered across the city. But not everyone gets to be an attendee. For people with visual and mobility barriers, access to prominent cultural centres in Delhi is marked, sometimes, by the inadequacy and, more often, the lack of accessible design and infrastructure.

The right to participate in cultural life

Discourse about people with disabilities is largely centred around medicine, ethics, policy, and education. Their right to participate in cultural life, as both audiences and artists, remains an afterthought in conversations and initiatives about inclusivity. Pulkit Sharma, an RJ and content creator who uses a wheelchair, shares: “People’s point of view about culture is not oriented towards people with disabilities. They think, “Kya karenge aa ke, kaun leke aayega?” (Why will they [people with disabilities] come? Who will bring them?)

Pulkit Sharma, an RJ and content creator who uses a wheelchair, shares: “People’s point of view about culture is not oriented towards people with disabilities. They think, “Kya karenge aa ke, kaun leke aayega?” (Why will they [people with disabilities] come? Who will bring them?)

Article 30 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recognisesthe right to ‘Participation in Cultural Life, Recreation, Leisure and Sport’ of people with disabilities. It states that all appropriate measures should be taken to ensure that they “enjoy access to places for cultural performances or services, such as theatres, museums, cinemas, libraries and tourism services, and, as far as possible, enjoy access to monuments and sites of national cultural importance.”

Without access to the venues where cultural programmes take place in Delhi, people with mobility and visual impairments are denied the right to participate in cultural life and to develop their own intellectual, artistic and creative potential on an equal basis with others.

How can cultural centres be made accessible?

UNICEF has formulated a comprehensive toolkit on accessibility with guidelines for designing buildings that are accessible for all people. This includes an Accessibility Checklist to assess whether a building can be accessed by people with visual and mobility impairments.

Using selected benchmarks of the Accessibility Checklist, a closer look at some of Delhi’s premier centres for cultural exhibitions and programmes – the National Museum, India International Centre and the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) – in enabling the right of people with disabilities to participate in cultural life reveals significant gaps in ensuring access to their premises.

For people with visual and mobility impairments to use pathways inside and around buildings, they should be flat, with no open holes or steps, and large enough to allow the circulation of multiple people at the same time. Directional tactile stripes should be installed to guide people.

Wheelchairs and ramps are used by people with mobility impairments as well as the elderly. The three venues surveyed have ramps that meet most requirements of the Accessibility Checklist: the ramps are straight, their beginning and end are flat with no steps, and landing spaces are away from door openings.

However, where these accessibility measures are present, negligence in their construction and maintenance renders them difficult to use or entirely inefficient. “At times, ramps are too steep, elevators are not conveniently located, or accessible pathways are blocked by furniture. Accessible washrooms may not have adequate space for wheelchair manoeuvring. Sometimes, accessible entrances are at the back, which creates a sense of exclusion,” says Vinayana, a guest lecturer at Delhi University and a person with cerebral palsy, about her experience of attending cultural programmes at the India International Centre and the National Gallery of Modern Art.

Many buildings, at large, fail to accommodate accessibility needs beyond the popular imagination of inclusion and disability. “Accessibility begins with basic physical infrastructure – step-free access, functioning lifts, and accessible washrooms. Equally important are elements like clear signage, ramps with proper gradient, trained staff who are sensitised, and accessible modes of communication for people with different kinds of disabilities,” says Vinayana.

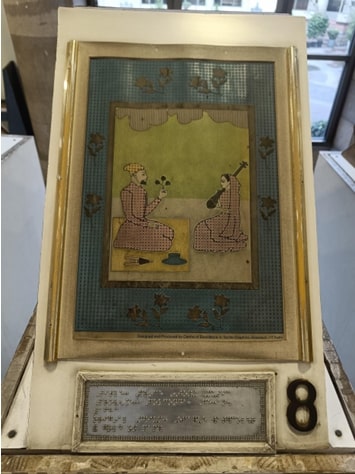

Doors should have identifying signs with text, symbols, Braille, and photographs next to them. If an entry door is made of glass, there should be marks adhered to the glass to alert people. Out of the three surveyed cultural centres, only the National Museum has doors with identifying text above them and only the India International Centre carries signage and Braille on some doors.

Doors should also be easy to open and have handles at an appropriate height. While the National Museum and NGMA have lightweight doors, they lack handles that enable wheelchair users to open and close them with ease. The only accessibility requirement met by all three venues was doors that are wide enough to allow wheelchairs to pass.

Such lapses in design can render an entire building inaccessible to people with disabilities. It is important for every pathway, every floor, and every other component of a building to fulfil all measures of inclusive design to make the building seamlessly navigable for all users. The case of elevators and staircases further highlights how access remains incomplete in Delhi’s cultural centres.

For staircases to be accessible by people with visual impairments, they must have tactile strips on the top and bottom and Braille signage plates with information about the floor. There must be handrails on both sides, unobstructed and flat landing spaces, and regular steps with the same rise and tread. None of the three venues fulfils these requirements.

The National Museum and the NGMA have elevators large enough for people using a wheelchair to manoeuvre inside the cabin or, at least, allow them to enter and exit comfortably. They also have control panels situated at a comfortable height for wheelchair users to use and tactile and Braille signage for people with visual impairments.

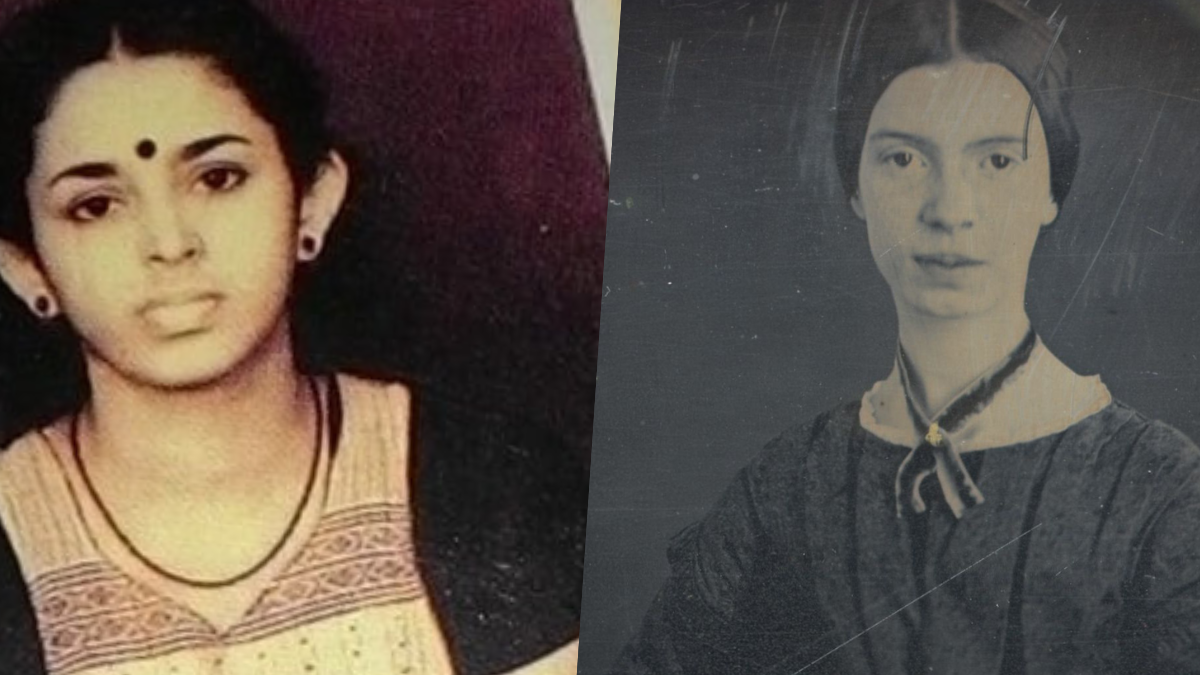

“These two cultural centres are accessible in all ways,” says Rajeev, a vocalist and the founder of Ahand Band, a collective of visually impaired musicians. “They have ramps for visually impaired artists to access the stage and guides to provide tours. Woh saari cheezein hain (wahan) joh honi chaahiye.” (“They have all the necessary features.”)

However, all three cultural centres failed to meet all requirements which make elevators accessible for people with visual and mobility impairments, such as having audio information about the floors, being close to the entrance of a building and being reachable without climbing stairs, which poses a challenge for wheelchair users to enter buildings.

Reaching to such spaces is a challenge in itself

For people with disabilities, reaching cultural centres becomes a challenge in itself, riddled with unreliable public transport and infrastructure. “Cultural centres are not accessible until roads are,” says Rajeev.

Travelling by public transportation in Delhi poses many challenges for people with disabilities: metro stations are often far away from cultural centres, roads are not pedestrian- and wheelchair-friendly, and lifts and ramps tend to be absent or poorly maintained in public areas. “Delhi has a lot of work left until its cultural life becomes accessible. If there is accessibility, it should be given fully,” remarks Pulkit. At large, only 8695 buses in India are fully accessible for people with disabilities as of February.

As a musician, Rajeev notes that cultural centres undertake expenses for music licensing while permanent Indian Sign Language interpreters are not hired. Live captioning, easy-to-read communication materials and audio descriptions, all of which assist people with visual impairments, are largely absent from cultural programmes held in Delhi.

For people who use wheelchairs, accessible seating inside auditoriums is hard to find. When they are present, these seats tend to be away from where the rest of the audience, including accompanying family and friends, are seated. Interestingly, while some cultural centres may have ramps at the entrance of auditoriums and conference rooms, ramps leading to the stage are an uber-rare phenomenon. Moreover, posters and online promotional materials about cultural programmes rarely indicate whether the venues are accessible for people using wheelchairs.

People with disabilities who belong to marginalised socio-economic backgrounds face additional barriers to access, such as the high cost involved in travel, entry and participation fees and the lack of personal assistance at venues. Little to no community and institutional support in securing their basic needs and dignity, coupled with social stigma and exclusion, leaves little scope for their participation in cultural and artistic life.

When the premier cultural institutions in Delhi struggle to ensure seamless access and inclusive programming for people with visual and mobility impairments, the answer to whether cultural spaces in the city at large are inclusive becomes obvious. A mixture of inconsistent implementation, inadequate maintenance and, most commonly, absence of inclusive infrastructure makes most auditoriums, art galleries, lecture halls and other cultural centres in Delhi inaccessible for people with visual and mobility impairments.

About the author(s)

Ishita is a freelance journalist based in Delhi. She is interested in writing and researching about accessibility, gender and popular culture.