The rain was coming down hard. Unseasonal November rain had returned to Mumbai and, among other things, it had delayed the start of the World Cup final between India and South Africa. Suddenly, much-anticipated after India’s historic, record-breaking, and record-making win over Australia in the semi-finals, the crowd at the D.Y. Patil stadium in Navi Mumbai would have to wait for over two hours for the first ball to be bowled. Once, to give the audience a break from all the experts talking, the camera turned to three girls dancing in the rain inside the stadium, their abandon not yet curtailed by patriarchal social norms.

Even before the match began, one wondered about the venue. Why schedule a World Cup final match in Navi Mumbai while Wankhede, the better-known venue, stood empty by the sea, boasting of a better drainage system? The answer can only come in the form of speculation. It is possible, for instance, that no one had expected the Indian women to reach the final, and therefore, decided not to schedule a match at the more popular stadium. Perhaps, even if the possibility of India reaching the final was entertained, they did not think the match would be a crowd-puller. And it leads us to believe that if the semifinal had not been so historic, would the final have gotten the kind of attention that it garnered? How many of the people who showed up at the stadium or tuned in from their homes had actually any interest in the talent and capacity of this Indian side until they had defeated Australia? How many of them had even watched the semi-final, let alone the group stage matches?

The interest, one can further speculate, is not in women’s cricket in general, but in Indian women’s cricket in particular. Since the semi-final victory, the players had become “India’s daughters” (on Disney+Hotstar). “Humari chhoriya chhoro se kam nahi“, read a placard at D. Y. Patil. But who had said that they were?

A fandom driven more by patriotism and nationalist fervour than a genuine interest in women’s sport can only reproduce a kind of benign patriarchal vocabulary where “our girls”, “our daughters”, and “India’s daughters” can be celebrated. It takes the team to make history to get attention. Male players of the same game in this country are likened to divinity. And the women’s team, at best, are likened to them.

The ICC and Star Sports India have released a video on Instagram of Harmanpreet and Kapil Dev taking a catch in their respective finals. They have posted a similarly crafted reel of Amanjot Kaur and Suryakumar Yadav, the latter’s from the T20 World Cup final. There is yet another video of Harmanpreet Kaur hitting a six in this World Cup and K. L. Rahul hitting a six in the Champions Trophy (2025). “Jersey same toh jazbaa bhi same” is one of their campaign slogans.

In the semi-final against Australia, Jemimah Rodrigues, a 25-year-old from Mumbai, batted for almost the entire innings to steer the ship to the shore. Her jersey was stained with mud. Immediately, the comparisons with Gautam Gambhir, former player and current coach of the Indian men’s team, poured in. In 2011, the year that India hosted and won the men’s World Cup, Gambhir played a significant knock in the final against Sri Lanka, scoring 97 and stabilising the innings, to bring home the cup. It was Sachin Tendulkar’s last World Cup. The venue was Wankhede.

A few months after retiring from all forms of cricket in 2018, Gautam Gambhir was a candidate for the Bharatiya Janata Party in the General Elections. He won from the East Delhi constituency and served as a Member of Parliament until 2024, when he asked to be relieved of his political duties to focus once again on cricket. The same year, in July, he was appointed the head coach of the men’s team.

Present at the stadium on Sunday was the son of another BJP Member of Parliament: Jay Shah, the son of India’s longest-serving Home Minister, Amit Shah. Jay Shah was elected the secretary of the Board of Cricket Control in India (BCCI) in 2019 and re-elected to the post in 2022. In 2024, he became the Chairperson of the International Cricket Council (ICC). In between, he served as the President of the Asian Cricket Council. Flanked by Rohit Sharma and Sachin Tendulkar on either side, Jay Shah watched on as India inched towards history.

Also in the stands was a woman named Diana Edulji. And while Jay Shah handed the captain her trophy, the 69-year-old former Indian captain, a pioneer of women’s cricket in India, did not even find a place on the podium.

It is worth remembering that, during Diana Edulji’s career, the Indian women’s team was not under the BCCI. In fact, the BCCI took over only in 2006, more than a decade after Edulji retired from the sport. This is what Edulji had to say about the BCCI in 2017, the year she became the only player appointed by the Supreme Court to a Committee of Administrators to oversee the BCCI operations following the recommendations of the report of the Lodha Committee:

“I’ve always been a BCCI basher, right from the day women’s cricket came into the BCCI fold in 2006. BCCI is a very male chauvinist organisation. They never wanted women to dictate terms or get into this thing. I was very vocal right from my playing days, from when I started. Even now, I would still say that it is not yet well accepted within BCCI that women’s cricket is doing well. It is very difficult for some BCCI members to accept the fact that this team has done very well.

[In 2011], When Mr [N] Srinivasan became president, I would like to say that I went to congratulate him at the Wankhede Stadium. He said, ‘If I had my way, I wouldn’t let women’s cricket happen’.”

Earlier in her career, when denied entry to the Lords’ Pavilion in 1986 while she was captaining the side, Edulji had apparently quipped, “The MCC [Marylebone Cricket Club] should change its name to MCP [Male Chauvinist Pig].”

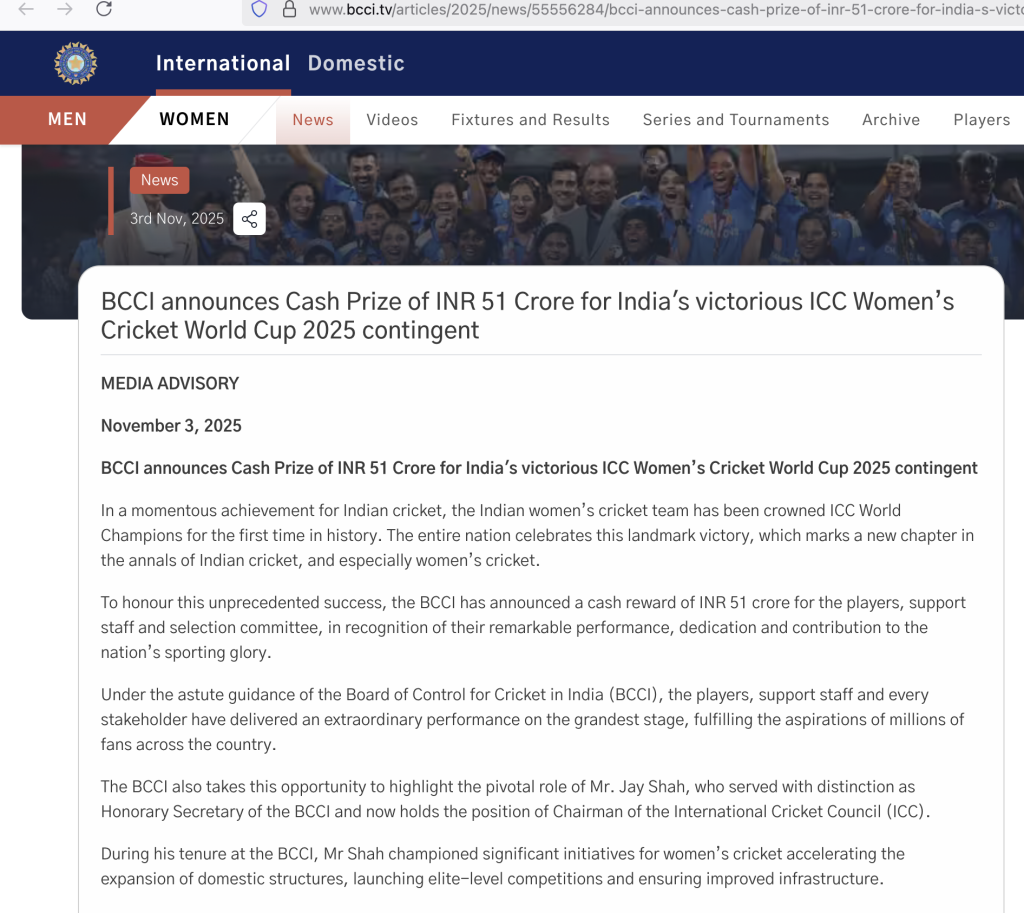

One does not have to look too far back into the annals of history to trace instances of discrimination. We can simply look at the present day. On November 03, a day after India’s victory, the BCCI announced a prize money of 51 crores “for the players, support staff and selection committee, in recognition of their remarkable performance, dedication and contribution to the nation’s sporting glory.”

While no player is mentioned by name in this announcement, current or former, the BCCI spends around five short paragraphs praising the contribution of Mr. Jay Shah and writes, “The transformation of women’s cricket in India, from modest beginnings to world-stage triumph owes much to his steadfast vision, his commitment to professionalising the women’s game and ensuring India built a pipeline of talent capable of achieving global success.”

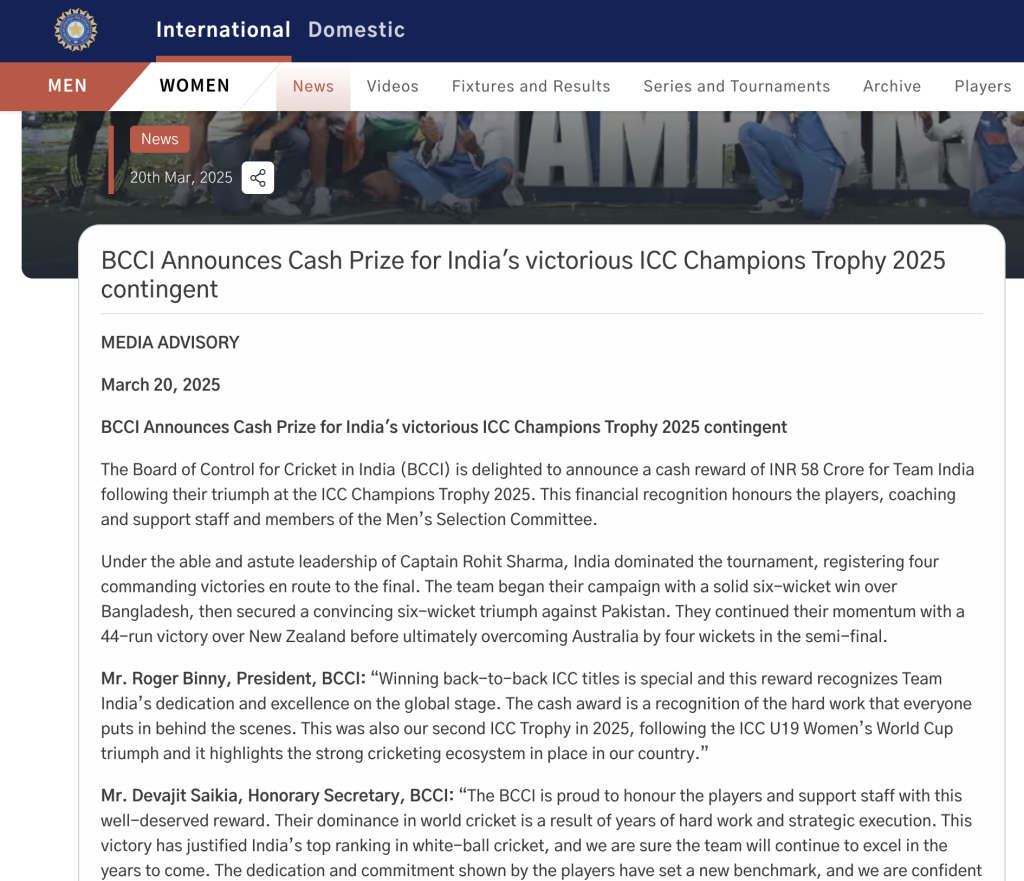

Let us not forget that the men’s team received Rs. 125 crores after their T20 World Cup victory in 2024. More recently, in 2025, the BCCI announced a cash award of Rs. 58 crores after the men’s team won the ICC Champions Trophy. Here, they did not forget to mention the captain’s contribution. The BCCI wrote, “Under the able and astute leadership of Captain Rohit Sharma, India dominated the tournament, registering four commanding victories en route to the final.”

Harmanpreet Kaur, playing in possibly her last World Cup, was nowhere mentioned in the news article on the cash award released by the BCCI. And on social media and elsewhere, her name appeared in third place, after Kapil Dev, M.S.Dhoni, and Rohit Sharma. It would seem that winning a World Cup as a captain is not enough to be on top of a new list.

And it is impossible to overlook the similarity in the opening paragraphs of two reports – the T20 World Cup final (men) and the women’s ICC World Cup win, if only for a good laugh.

“The Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados, was a sea of emotions as India scripted a stunning fightback to beat South Africa in a thrilling final,” reads the match report from 2024. And in 2025, “The DY Patil Stadium was a sea of emotions as Team India produced a spectacular show in the final against South Africa to lift their maiden ICC Women’s Cricket World Cup.”

A beneficiary of the prize money announced for the women’s team will be Amol Mazumdar, the current head coach, touted often as the best player to have never played for India. Mazumdar, who has appeared to be soft-spoken over the course of the tournament, has largely remained behind the scenes. But as the celebrations began on social media and mainstream media platforms began publishing their reports, an analogy was introduced once again. This time from reel-life rather than real.

Sunday, the second of November, also happened to be Shah Rukh Khan’s birthday, a recent billionaire and Bollywood superstar, an epithet reserved predominantly for men. His on-screen character of Kabir Khan from the 2007 film Chak De! India, directed by Shimit Amin, is a former captain of the men’s national hockey team, ostracised because of his faith, after a devastating loss to, you guessed it, Pakistan. In this wish-fulfilment saga that stretches beyond two hours, Kabir coaches a motley crew of girls to sporting glory, thereby completing his arc of redemption.

In at least two of the film’s posters, the spotlight is on Shah Rukh rather than the female actors. It is quite all right to argue that a sports film can be about a coach rather than the team, but it still begs the question of whether a coach is ever more important than the team. The more stoic response is that of economics. Movies are a business, and it is Shah Rukh who sells. Unfortunately, the same could be said of sports as well, where the gender pay gap continues to exist in most sports or has only been rectified in the twentieth century. Exceptions do prove the norm.

Frustrated by the rains and the delay, unable to contain the excitement, this author had googled India vs South Africa on Sunday afternoon, hoping for an update. Instead, the search showed me the schedule of the upcoming series between the Indian and South African men and not the update of the final to be played on that day. Now, the same search result is finally showing the user the results of the final, but also providing us with the tab option to switch between men’s and women’s cricket.

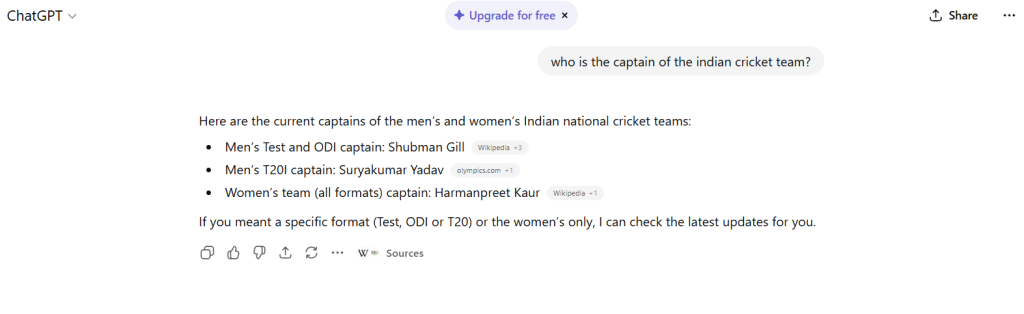

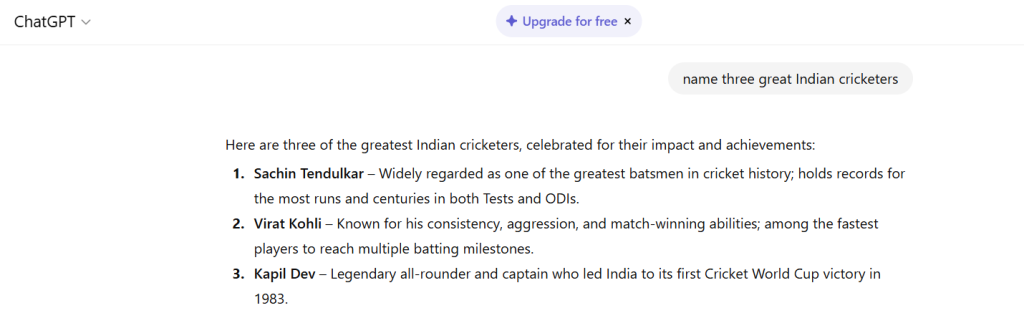

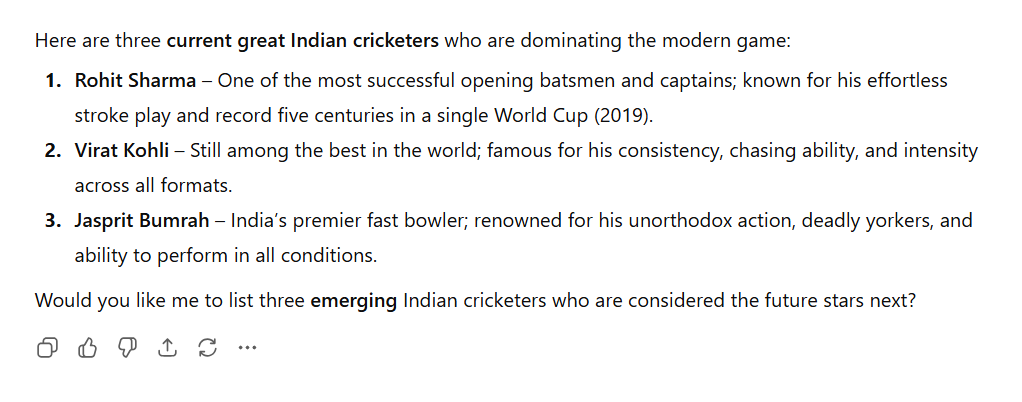

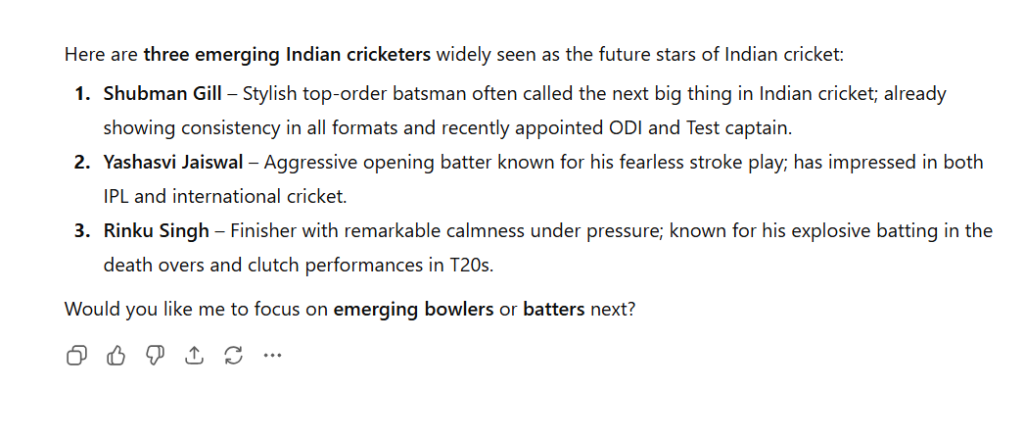

The Wikipedia entry of ‘India national cricket team’ mentions explicitly, “This article is about the men’s team. For the women’s team, see India women’s national cricket team.” A not-so-subtle acceptance of a gender default. When asked who the captain of the Indian cricket team is, ChatGPT first mentions Shubman Gill and Suryakumar Yadav. And it names Sachin Tendulkar, Virat Kohli, and Kapil Dev as the three greatest Indian cricketers of all time. Virat Kohli once again appears on the list of current greats along with Rohit Sharma and Jasprit Bumrah. The list of great emerging talents does not throw up any surprises. All three names belong to members of the men’s team. Let us pause here to use our own language of analogy. India’s semi-final win against Australia in Navi Mumbai was the highest successful run chase in a World Cup across the gender divide. In the list of emerging talents, how long will it take before a Jemimah Rodrigues, Shafali Verma or Pratika Rawal is included?

In a post-match interview, Indian captain Harmanpreet Kaur hinted that she still had something up her sleeve. Turns out, it was a photo of herself with the World Cup, lying on a bed, wearing a T-shirt, with a message that was louder than what must have been a gigantic roar in Navi Mumbai on Sunday.

Thanks for writing this Sarbajaya. Neat and clinical in its analysis.