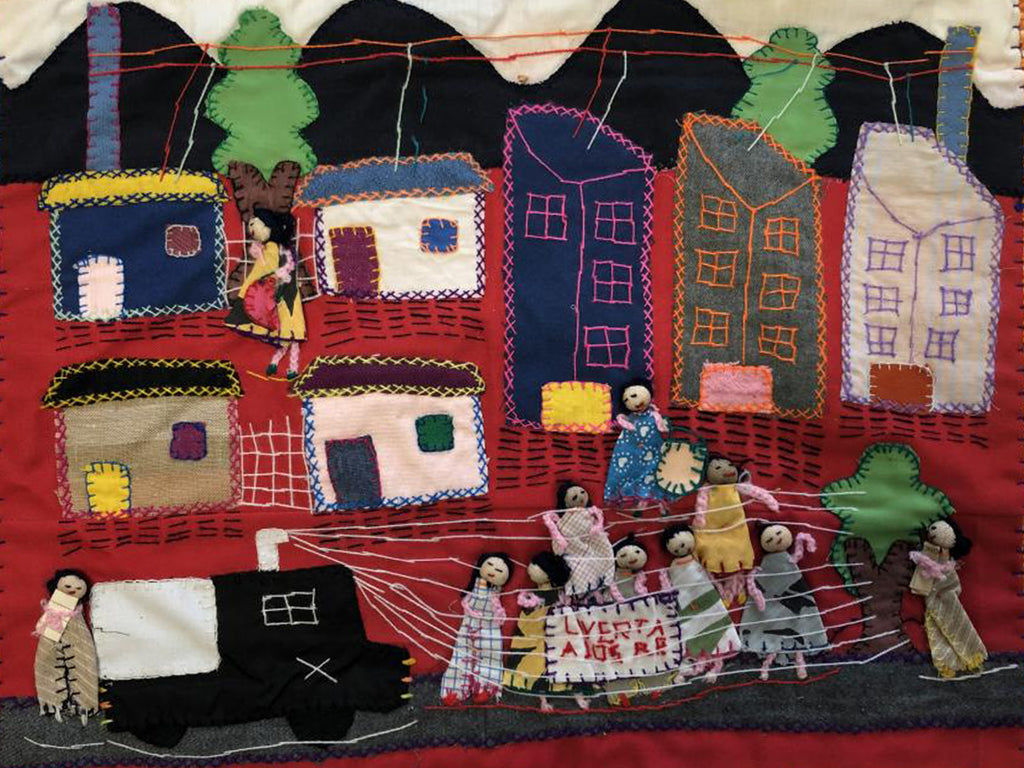

On a quiet evening in Santiago in the late 1970s, a Chilean mother sewed on a piece of cloth. She used pieces of her missing son’s shirt to make a small quilt, who had disappeared during General Pinochet’s dictatorship. She made a quilted picture of the memory. A soldier takes away a man. A mother tries to hold her child tightly. A house is left open and broken. These quilts are called Arpilleras, which were stitched in kitchens, church basements, and secret workshops throughout Chile. These were secretly sent abroad to show the human rights abuses taking place in Chile, even though the dictatorship had banned free speech, protests, and the press.

In one such testimony that has been preserved in Santiago’s museum of memory and human rights, arpillerista Doris Meniconi has added, ‘For me, arpillera is a cry from the soul that can’t be spoken but is expressed. A form of rebellion, of crying out for my son’s absence‘.

Across time and place, women have turned to sewing to survive and share their stories, especially when they had no voice or space ever to be heard.

Weaving as recordkeeping by women: a global feminist context

Textiles are often dismissed as “ornamental” or merely “women’s work,” often reduced to domestic activities considered less important than painting, literature, or other official archives. Art historian Rozsika Parker, has argued in The Subversive Stitch (1984) that ‘The art of embroidery has been the means of educating women into the feminine ideal, and of proving that they have attained it, but it has also provided a weapon of resistance to the constraints of femininity.’

Parker’s work showed us that embroidery is not trivial but carries a double meaning: both discipline and defiance. Fabric has always held cultural and political meaning. From Andean weavings that preserve indigenous knowledge to African-American quilts in the 19th century that recorded community histories, needlework has always served as a living archive.

From Andean weavings that preserve indigenous knowledge to African-American quilts in the 19th century that recorded community histories, needlework has always served as a living archive.

Feminist recordings highlight that these pieces are not only art but a record of survival. These threads of fabric, at times, preserve memory in ways words often cannot. Textile memory is most evident in contexts of colonisation, dictatorship, gender violence, or forced migration, especially when women’s voices are silenced.

Kantha: threads of survival in Bengal

In Bengal, women made Kantha quilts by layering old saris and stitching them. These were created in rural homes, but they created more than just practical value.

Kantha has also emerged powerfully in times of life. In refugee camps during the Partition of 1947, women made Kantha quilts from torn clothes, stitching warmth from loss. Later, during the Bangladeshi Liberation War of 1971, Maleka Khan, a social worker and author, noticed how deeply the trauma impacted women. When they were unable or unwilling to talk about what they had endured, Kantha became a quiet way of processing the trauma and regaining strength. ‘By making kanthas together, we eventually helped some of the victims to become stronger. By occupying them in an everyday skill that they enjoyed, it allowed their subconscious minds to cope and overcome,’ she said.

Over time, Kantha has grown from a household heirloom to a museum art form. In the 1970s and 1980s, feminist artists like Nelly Sethna revived embroidery to reclaim textile traditions. Today, Kantha continues as a feminist record carrying women’s lives, grief, and resilience in its very fabric.

Arpilleras: dictatorship, disappearance, and women’s protest in Chile

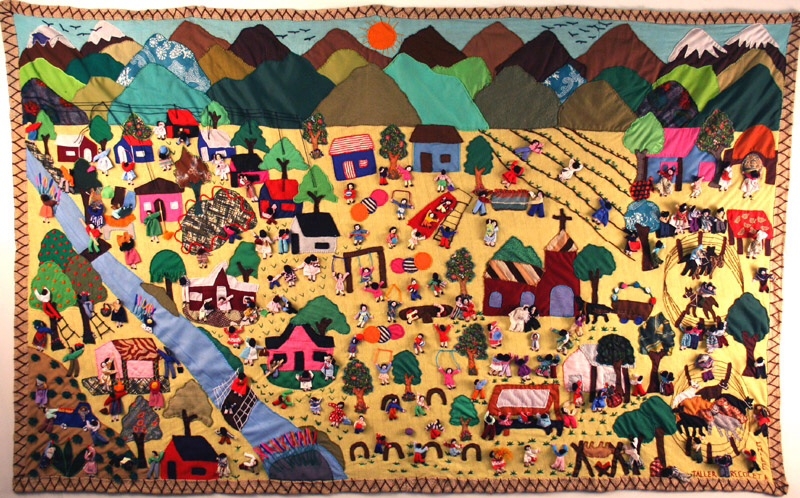

During Pinochet’s dictatorship, women made arpilleras, stitched cloth pictures, to speak out against the injustice. There were workshops organised by the Catholic church which brought together women from Santiago’s shantytown, giving them both comfort and a way to earn a little money.

During Pinochet’s dictatorship, women made arpilleras, which are stitched cloth pictures to speak out against the injustice happening.

Sociologist Jacqueline Adams explains in his book Art Against Dictatorship: Making and Expanding Arpilleras under Pinochet how these workshops helped them show their struggle while expressing their creativity. The finished arpilleras were smuggled abroad, where they exposed the violence taking place in Chile and spoke when words could not.

An arpillerista, Natalia, explains in the book Art Against Dictatorship: Making and Expanding Arpilleras under Pinochet (2013), ‘Because it’s something that you had in your hands and were working on with love, and knowing that it was all going to go abroad, and they would see the reality of what was happening in Chile. Because it was like a letter, you understand, a letter. Via this letter you were telling people how we were faring here. An open letter, something which, how can I say, something very personal but which at the same time was going over there and was going to be useful because it was going to say, “This is happening in Chile,” you understand?‘ (p 234) Her very words capture how Arpilleras turned these women’s private pain into a collective voice against dictatorship.

Hmong story cloths: migration and cultural survival

In Laos and among Hmong refugee communities across Southeast Asia, women made paj ntaub, which means “story cloths.” These are embroidered fabrics that depict everyday life, folklore, and journeys of migration. After the U.S. Secret War in Laos and the displacement of Hmong families, these clothes became visual stories of violence and exile.

The art historian Phyllis Teo explains in her review of Hmong Reverse Appliqué: Cultural Meaning and Significance (2022) by Linda A. Gerdner states that ‘The rich tradition of storytelling through embroidered cloth allows Hmong elders to communicate history, tradition, and folklore to both a wider international audience and with younger generations of Hmong raised in the United States.’

In the refugee camps, the clothes were sold to support families, where we see survival blending with the act of remembering.

In the diaspora, the clothes served as a means of cultural preservation. Mothers taught their daughters embroidery as a means of sustaining their identity. In the refugee camps, the clothes were sold to support families, where we see survival blending with the act of remembering. Thus, the paj ntaub shows how textiles can represent both trauma and cultural continuity simultaneously, thereby keeping stories of survival alive.

Feminist reclamation of textiles

Textile activism is thriving globally today. In Rajasthan, groups like Sadhna help women earn a livelihood while honouring their creativity. In the U.S., artists like Judy Chicago and Faith Ringgold are turning needlework into art that carries feminist and political ideas. Across these practices, we find a shared purpose: to reclaim textiles from being dismissed as “women’s work.” Thread, needle, and cloth become tools by which women can share their experiences of labour, loss, and survival. These works show that the experiences within the kitchen, refugee camps, and sewing circles are not trivial matters at all but important parts of our history.

When women’s work is taken seriously, it tells feminist tales of survival. Clothes serve as an archive when words and history are silenced. The Chilean woman stitching her missing son’s shirt, the Bangladeshi woman layering worn saris into a kantha, and the Hmong refugee using embroidery to sustain themselves were not just about making art, but healing and sharing their stories. Textiles have always been used to preserve memory and document resistance across continents. These textiles form a shared feminist theory where the needle becomes a voice against erasure.

About the author(s)

Juhi Sanduja is an Editorial Intern at Feminism In India (FII). She is passionate about intersectional feminism, with a keen interest in documenting resistance, feminist histories, and questions of identity. She previously interned at the Centre of Policy Research and Governance (CPRG), Delhi, as a Research Intern. Currently studying English Literature and French, she is particularly interested in how feminist thought can inform public policy and drive social change.