There’s a particular cruelty in watching a ghazal written in defiance become the soundtrack to conformity. Sahir Ludhianvi’s “Na toh karwaan ki talaash hai” from the 1960 film Barsaat Ki Raat is a meditation on spiritual seeking. It transcends material pursuits. It has found itself trapped in 2025’s most dissonant cinematic marriage.

In Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar, this 13-minute qawwali originally composed by Roshan plays over scenes of what can only be described as sexy violence and loud aggressive jingoism. Roshan was Hrithik Roshan’s grandfather, by the way. A man who probably never imagined his composition would one day soundtrack this kind of fury. The irony would be laughable if it weren’t so tragic. Even Hrithik himself praised the film on Instagram while noting he “may disagree with the politics of it” and questioning “the responsibilities filmmakers should bear as citizens of the world.” The backlash was swift. He faced massive trolling for daring to suggest nuance in a climate that demands absolute loyalty.

But the degradation doesn’t end there. The ghazal has been chopped up, remixed as “Karwaan,” and served as trending audio for Instagram’s latest viral phenomenon: “First day as a spy in Pakistan” reels. Content creators across India have mindlessly performed skits about Hindu spies revealing themselves in Pakistan by accidentally saying something “very core to their identity.” The humor, if you can even call it that, relies entirely on cultural othering. It reduces Muslims and Pakistanis to a monolith. One that can apparently be infiltrated just by performing Muslim identity badly enough.

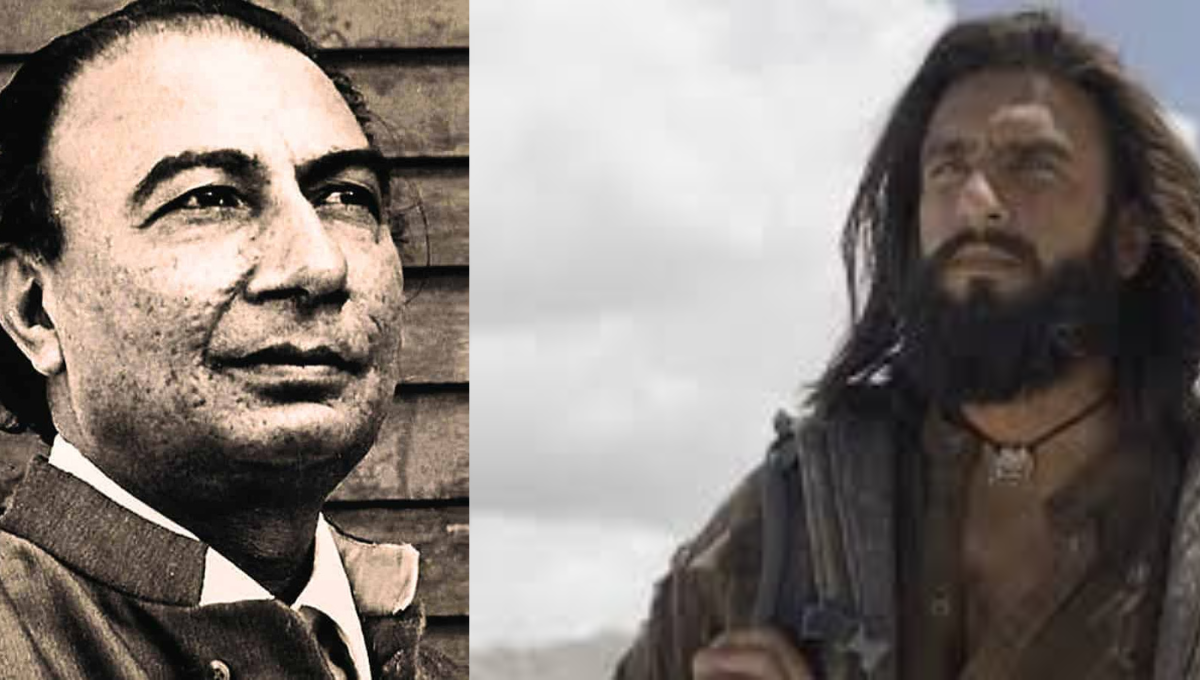

These creators don’t know they are dancing on Sahir Ludhianvi’s grave. They don’t know that the man who wrote those words fled Lahore in 1949 with a warrant for his arrest. His crime? Daring to promote Communist ideals. They don’t know that Sahir was born Abdul Hayee. That his parents’ bitter separation shaped everything he would write. That his mother, Sardar Begum, left her husband and forfeited all claims to financial security just to escape an abusive marriage. When young Sahir was asked in court who he wanted to stay with, he chose poverty with his mother over wealth with his father without hesitation.

The chopped up ghazal, remixed as “Karwaan,” served as trending audio for Instagram’s latest viral phenomenon: “First day as a spy in Pakistan” reels. Content creators across India have mindlessly performed skits about Hindu spies revealing themselves in Pakistan by accidentally saying something “very core to their identity.” The humor, if you can even call it that, relies entirely on cultural othering. It reduces Muslims and Pakistanis to a monolith.

They don’t know that Sahir once said, “In his entire life, Sahir loved once, and he nurtured one hate. He loved his mother, and he hated his father.” They don’t know he was a member of the Progressive Writers’ Association. That he spent his entire life writing against exactly the kind of dehumanization their memes celebrate. As Javed Akhtar noted, Sahir was “not just a poet but a public philosopher.” His work questioned “blind nationalism that ignores the grim realities of inequality and injustice.”

The ghazal they are butchering literally begins with a rejection of worldly quests. “Na toh karwaan ki talaash hai, na humsafar ki talaash hai. I’m not seeking a caravan, nor a companion.” It’s about seeking something beyond the material. Beyond the noise. To appropriate it for a film that trades in blood soaked nationalism is one kind of violence. To memeify it into cultural supremacist content is another. Together, they perform an autopsy on meaning itself.

The violence of silencing

The bitter irony deepens when we examine what happened to those who dared critique Dhurandhar. Anupama Chopra’s review on The Hollywood Reporter India described the film as “exhausting, relentless, and frenzied.” Driven by “too much testosterone, shrill nationalism, and inflammatory anti-Pakistan narratives.” It was taken down within days.

Whether the deletion came from coordinated online harassment is one question. Veteran actor Paresh Rawal tweeted at her: “Aren’t you tired of being Miss Irrelevant?” Whether it came from corporate pressure is another. Both Chopra’s platform and the film’s music label are owned by RPSG Lifestyle Media. The conflict of interest sits there, obvious as a wound. What’s certain is that the review vanished. Chopra faced what was documented as rape threats and violent messages. The usual playbook when women say things the internet’s defenders don’t like.

Sucharita Tyagi, vice chairperson of the Film Critics Guild, faced similar abuse. Her review highlighted the film’s repeated, aggressive display of hyper masculinity. She noted the ending line: “Yeh naya Hindustan hai. Yeh ghar mein ghusega bhi, aur maarega bhi. This is New India. It will enter homes and kill too.” She dared to suggest something sinister hummed beneath the surface. For this, she was subjected to coordinated attacks. Users accused her and other critics of being Pakistan-apologetic. They constructed elaborate conspiracy theories to dismiss the systematic harassment. The gaslighting was breathtaking in its audacity.

These creators don’t know they are dancing on Sahir Ludhianvi’s grave. They don’t know that the man who wrote those words fled Lahore in 1949 with a warrant for his arrest. His crime? Daring to promote Communist ideals. They don’t know that Sahir was born Abdul Hayee.

The Film Critics Guild issued a statement condemning the “targeted attacks, harassment, and hate directed toward film critics.” The statement noted that “what began as disagreement has rapidly devolved into coordinated abuse, personal attacks on individual critics, and organised attempts to discredit their professional integrity.” But even this was mocked. Critics pointed out that the statement was issued by an organization chaired by Chopra and vice chaired by Tyagi. As if this circular logic somehow invalidated their experience of harassment. As if receiving death threats becomes acceptable if you complain about it with your colleagues.

Freedom of expression dies in the comments section

This is where Sahir’s legacy burns brightest and most painfully. The poet who wrote: “Jinhe naaz hai Hind par woh kahan hain?; Where are those proud of India?,” delivered a stinging rebuke to false patriotism. The question remains devastatingly relevant. He stood for exactly the kind of fearless dissent that Dhurandhar’s defenders seek to crush.

Sahir consistently wrote against oppressive structures of power. He refused to mould his poetry to suit others’ demands. He maintained what scholars describe as “socialistic conviction, courage and dissent.” Think about the man who literally fled one country because he chose exile over silence.

His anti-war poem Parchhaiyan (Silhouettes) made a fervent plea: “Come let’s tell these powerbrokers, that we hate jingoism that leads to war.” He wrote of how war devastates not just nations but the very fabric of human relationships. How “in the brothels of capitalism, the youth of sisters is put on sale.” He championed women’s dignity at a time when few male poets did. “Aurat ne janam diya mardon ko/ Mardon ne usse bazaar diya. A woman gave birth to men, men turned her into merchandise.”

What makes this entire episode so devastating is how perfectly it embodies what it destroys. Dhurandhar uses Sahir’s poetry about transcending material quests in a film obsessed with territorial conquest. Instagram creators use his words about seeking higher truths to create content that reduces complex geopolitical tragedies to cheap comedy. And when critics invoke the very principles Sahir stood for, they are hounded offline.

This was a man who understood that dissent is not anti-national. It’s essential to democracy. That criticism is not betrayal, it’s care. That questioning power is not a weakness, it’s strength. When Sahir wrote in his revolutionary poem Avaaz-e-Adam, “Dabegi kab talak aawaz-e-Aadam, hum bhi dekhenge,” he was speaking directly against intimidation. How long will the voice of humanity be suppressed, we too shall see. The poem was literally what forced him to flee Lahore. But he never stopped speaking truth to power. He couldn’t. It was not in him to be silent.

The death of irony is the birth of amnesia

What makes this entire episode so devastating is how perfectly it embodies what it destroys. Dhurandhar uses Sahir’s poetry about transcending material quests in a film obsessed with territorial conquest. Instagram creators use his words about seeking higher truths to create content that reduces complex geopolitical tragedies to cheap comedy. And when critics invoke the very principles Sahir stood for, they are hounded offline. The right to dissent. The responsibility to question. These things are treated as threats by the same forces that would have silenced the poet himself.

Film critic Uday Bhatia captured it perfectly in his tweet: “I can’t believe the filth so many critics here are being subjected to this week. A vile country, and a shitty industry that won’t stand up for critics but expects critics to stand up for them.” The Film Critics Guild’s statement noted that critics face “direct threats and vicious online campaigns aimed at silencing their perspectives.” This is the exact authoritarian impulse Sahir spent his life resisting.

Meanwhile, Dhurandhar collects hundreds of crores at the box office. The Instagram reels accumulate millions of views. Sahir’s words echo in a void that has forgotten what they meant. The poet who wrote “Jism ki maut koi maut nahin hoti” couldn’t have imagined this particular immortality. The death of the body is no death at all. But what about the death of meaning? His poetry living on, utterly lobotomized, conscripted into service for everything he opposed.

There’s a story about Sahir that haunts me. When he got his first royalty check, it was for Rs. 62.50. The publisher, Amar Verma, was ashamed to give him such a small amount. Sahir told him it wasn’t small at all. It was the first royalty of his life. A man who understood the value of being paid for your words. Who fought to be paid one rupee more than Lata Mangeshkar for every song. Not out of ego. Out of principle. Because lyricists deserved to be valued.

Perhaps the cruelest irony is this. Sahir wrote about seeking a caravan because he believed in collective human dignity. Dignity that transcended borders. The reels mock the idea that anyone could cross borders with dignity. The film fetishizes crossing borders with violence. And the critics who point out this degradation are told they have no right to speak. That their dissent itself is the real violence. That by pointing out the problem, they are the problem.

Sahir once wrote, Main pal do pal ka shaayar hoon. I am a poet for a fleeting moment. But moments, when forgotten, can become erasures. And now in 2025, we are watching the public execution of the very principles that made his poetry possible. The freedom to dissent. The courage to question. The insistence that art serves humanity rather than power.

The ghazal plays on. It trends on Instagram. It soundtracks violence in theaters across the country. Children who have never heard of Sahir Ludhiannvi make “funny” reels on his verses. Critics who dare to speak are silenced.

And no one remembers what Sahir was trying to say.

About the author(s)

Aaditya Pandey is a poet and freelance writer based in New Delhi. He writes about art, culture, politics and queerness. His previous works have been published in Deccan Chronicle, Live Wire and Poems India

Pathetic article. Learn to look beyond your gender identity. Make this world better by new content, creation vs complaining, crying, envy of someone else.

1000cr box office collection of that movie.

useless article is this 👎