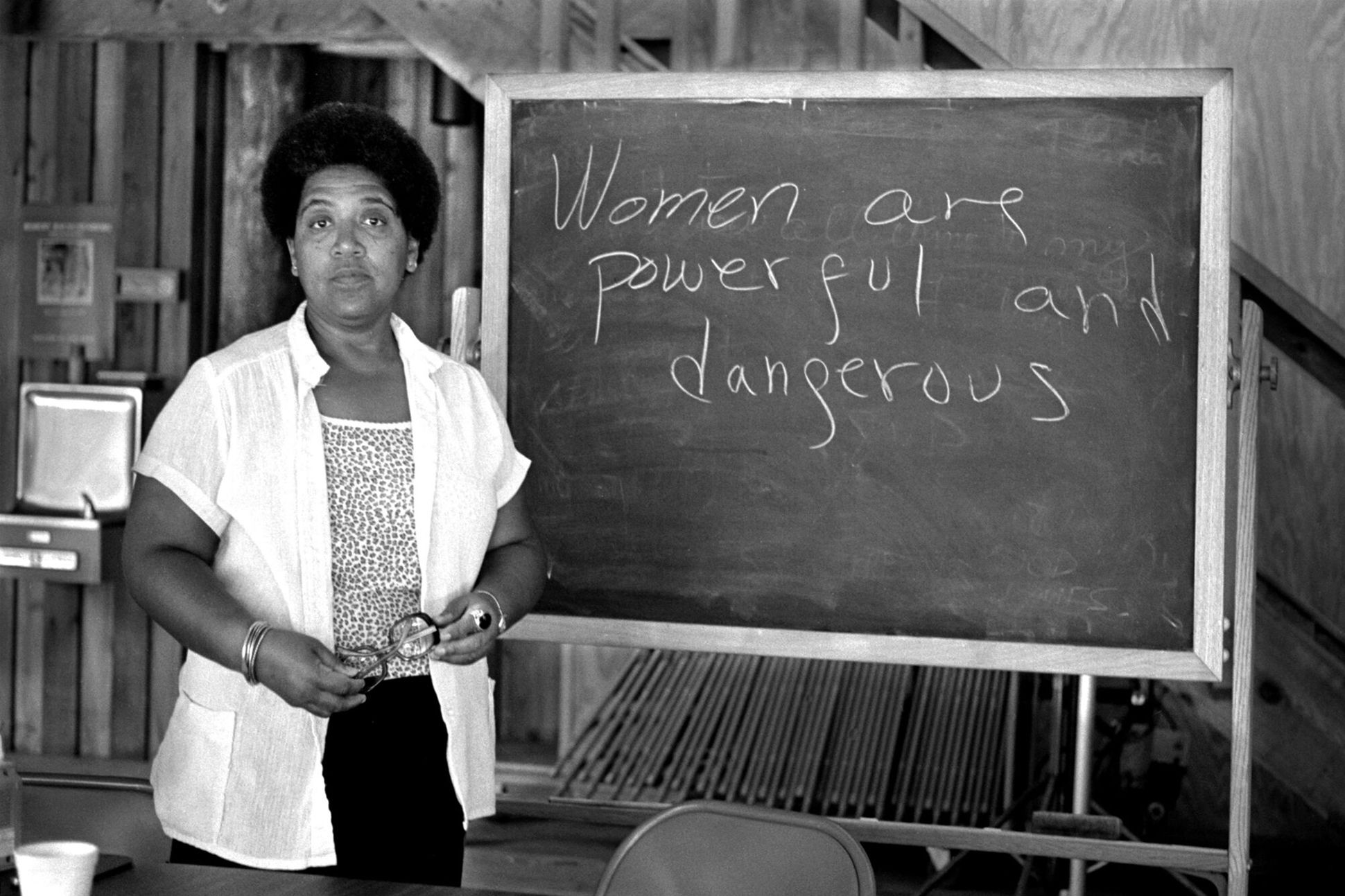

Audre Lorde described herself as ‘Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, and poet.’ It would be impossible to speak of her and her legacy in 2026 without adding a few more words: legendary, powerful, and relevant. One of the dynamic voices whose words caused just as much of a stir in academic conferences as it did amongst those who read her poetry, Lorde’s determination to keep talking about the need for inclusion and community continues to resonate with people across time.

Silver Press’ ‘Your Silence Will Not Protect You’ is a book that brings together Lorde the poet and Lorde the academic, as it starts with her papers and essays and ends with her poems. Published in 2017, about 25 years after the poet’s passing, it seems to still be commenting on current events and advising us on how to navigate the socio-political landscape. On the one end, this is a testimony to how timeless her insights are (even as some of the terminology used by her has come to be recognised as being problematic today), while on the other end, it is proof that anyone who says that all the ideas of social justice that we talk about today are ‘too new’ for the older generations to understand or bring into their value system is basically erasing history and all the work that has been done by marginalised feminists around the world to bring us where we are.

On the need to Speak Up

With governments around the world silencing free speech with both overt and covert means, the popular advice coming the way of marginalised people seems to be to stay silent for our own sakes. There is absolutely nothing new about this- in fact, telling someone to stay silent is a very common way for those in power to keep oppressing and controlling everyone else. Lorde reminds us of the importance of speaking up. In the first paper ‘The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action‘ she urges us to move beyond fear by telling us that our silence will not prevent those who want to oppress us from doing that:

‘And I remind myself all of the time now that if I had been born mute, or had maintained an oath of silence my whole life long, for safety, I would still have suffered, and I would still die. It is very good for establishing perspective.‘

Furthermore, her essay makes the argument that if silence was such a good way of defending oneself, then it would essentially completely remove any fear or worry from our minds. Instead, those who remain silent when they know something extremely wrong is happening still carry that frightfulness inside them,

‘We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid.‘

Lorde talks not just about the importance of marginalised people speaking up but also the importance of actual allyship. She speaks of how so many Black Women’s voices are silenced because white women claim that the experiences are so distinct from their own that they can’t teach their work– she asks then, how it is possible for them to be teaching figures like Plato and Shakespeare? Her poetry often touches on this theme as well, as poems like ‘Good Mirrors are Not Cheap’ and ‘Need: A Choral of Black Women’s Voices’ talk about the importance of questioning those who are purposefully building false narratives, and standing together loud and proud as a community against injustices.

On Intersectionality

‘Intersectionality’ as a word was coined by Crenshaw in 1989, and it is important to remember that the critical race theorist was giving a name to what already was and not causing it to come into existence. Anybody who argues that it is a ‘new’ thing need only look at Lorde’s life and work to see how being marginalised in different ways has an impact on our experience of the world. She begins one of her essays by saying, ‘Black Feminism is not white feminism in blackface’, and a lot of her writing focuses on her lived experience of being excluded from so-called ‘inclusive’ places because some part of her identity threatened the exclusionary ideals that those places were built upon. In an open letter to Mary Daly, who was one of the white philosophers leading the feminist movement, Lorde stood up tall for herself and her sisters by saying,

“Mary, do you ever really read the work of Black women? Did you ever read my words, or did you merely finger through them for quotations which you thought might valuably support an already conceived idea concerning some old and distorted connection between us? This is not a rhetorical question.“

Lorde often directly called out and critiqued not just the overt exclusion but also the performative allyship within political movements and academic circles. While on the one hand, she was treated as the ‘other’ within the feminist movement for being Black- not just personally but as someone with a social identity- she was also often treated as being the ‘other’ in Black movements for being a woman and a lesbian. Her essays illustrate how the fact that her Black male comrades know the tools that the community uses to revolt against white people means that when she, as a woman and as a lesbian, attempts to use the same tools against oppression that comes her way through the misogyny of Black men, she is against an oppressor who already knows her language of revolt.

When it comes to fellow Black women, she sees herself as not being seen as one of them because the fact that she is a lesbian is seen as her being anti-Black (the accusation coming from the notion that lesbians will lead to Black people going extinct- because, you know, lesbians can magically convert everyone around them and no lesbian in the history of the universe has ever wanted a baby). She also talks about how the idea of seeing some people as not being ‘like me’ because something about their identity is different even though we share one oppressed identity comes from the feeling that ‘I must attack you before our enemies confuse us with each other.’ As Lorde reminds us, ‘But they will anyway.’

Other themes explored in the book include the importance of allowing yourself to feel angry against injustice and hate, the need for pathos to be a part of political discourse, and the vitality of the feminine and the loving in everything that we do and are. This compilation makes it obvious that ultimately her politics is a politics of the people– and that will always remain relevant as long as there are oppressors– no matter what they do or who they are.

About the author(s)

Khushi Bajaj (she/her) is an intersectional feminist and writer who holds an MSc in Media and Communications from the London School of Economics. Her work has previously been published by Penguin Random House, erbacce-press, Metro UK, Diva, Hindustan Times, and more. She is passionate about advocating for social justice and believing in the revolutionary capacity of kindness. She can be reached through email (khushi.bajaj1234@gmail.com).