The Bharat Bhavan Art Centre in Bhopal opened its door in February 1982. Among the mazdoors (labourers) hired to lay the bricks on which the gallery stands was a young woman from the Bheel tribe from a hamlet called Pitol of Jhabua district in Madhya Pradesh. She had been earning six rupees as a daily wage labourer. Her house burned and her family hurled into destitution, she was living in an oda (a makeshift hovel made out of grass). Hired away by contractors for months, she has recounted how she used to accompany her sister to work and provided for her family.

Later, she came to Bhopal as a mazdoor and worked on the site of construction of the Bharat Bhavan. For her, mazdoori meant subsistence. That the secrets of Lok-Darma (religion of the folk) was seething inside her she had no means to realise. Nor did she have the pleasure of being absorbed in art fascinations. Aware of her situation, she was fixedly determined to earn six rupees, so much so that when J. Swaminathan offered her ten rupees, she wanted to settle for six. Even though she was from a tribe that was known for their love of art, she did not have the privilege to while away her hours contemplating art. It was unusual for a woman from the Bheel community to leave their bartans and pick up the brush. Which is why when Swaminathan urged her to paint, she, in disbelief, could not assess what purpose her painting would satisfy and sort of interpreted the proposal as the whims of the babus.

Art, as it usually is, has been, for most of its history, for the one who can afford. Seen from the perspective of a mazdoor, to live with art is a rich endeavour which is why such a proposal sounded whimsical. What would art achieve her? Why are these people asking her to paint? Would it be prudent to trust them? Rightfully so, her apprehensions, which were driven by her awareness of who she was—an Adivasi woman—and what could happen to her if she is seen as transgressive, made her question if there were any other ulterior motives of a dariwala baba. She feared abduction. She says in an interview, “डर लगता था। कहाँ ले आएंगे, कहाँ बिठा लेंगे। तो वो बारे बारे बालवाला बाबा है, वो कही पटापुटो के ले जायेंगे। ऐसा कर के मैं डर रही हूँ अंदर से, डर भी लग रहा है।(I was scared. Where would they take me, where would they make me sit? That baba with the long hair — what if he takes me somewhere far away? Thinking like this, I was frightened from within, truly scared.)“

She had a right to panic as her fears were justified. Made aware of her position as an Adivasi woman, she had the right to doubt the motives of the men who had invited her inside the Bhavan to paint. The proposal was lucrative and lucrative could mean seduction. It seemed like a lure. So, when Swaminathan had invited her inside the Bhavan for painting, she refused to follow them and instead chose the mandir outside Bharat Bhavan as her place of work. She received fifty rupees for five days’ work and Swaminathan was impressed. However, the young woman could not understand what was so special about her work which earned her so much money. A year or so later, J. Swaminathan returned to her and asked her to paint more. This time, Swaminathan paid her fifteen hundred rupees for ten days’ work.

Among the mazdoors hired to lay the bricks on which Bharat Bhavan stands was a young woman from the Bheel tribe from a hamlet called Pitol of Jhabua district in Madhya Pradesh. Her name is Bhuri Bai.

Likhandara

Likhandara means ‘writing’. It also means someone who writes a lot. Among the Bheel community, Pithora is more than ‘art’. Mostly found in Dhar, Jhabua, and Nimar region in Madhya Pradesh, and sometimes also among the Bheel communities in Rajasthan and Gujarat, Pithora is an expression of tribal memory, mythology, music, and more. The mythological premise is a centuries-old religious ritual of worshipping water and the Indi King (the rain God—Indra). Usually, there is a Badwa (a local priest) who sings. They are accompanied by Dhank (a musical instrument) players. This is the setting that creates a mood for the Likhandara who paints according to the narrative of the song. It is story-singing, playing, painting, performing, and writing all done simultaneously. Traditionally painted on the façade of houses, Pithora murals act as a gesture of gratitude and welcome for guests who visit these houses. It would be puerile to classify the practice of Pithora as ‘art’ when the practice of ‘art’ has been annexed by those who can afford to practice ‘art’.

Bhuri bai’s mural-memoir

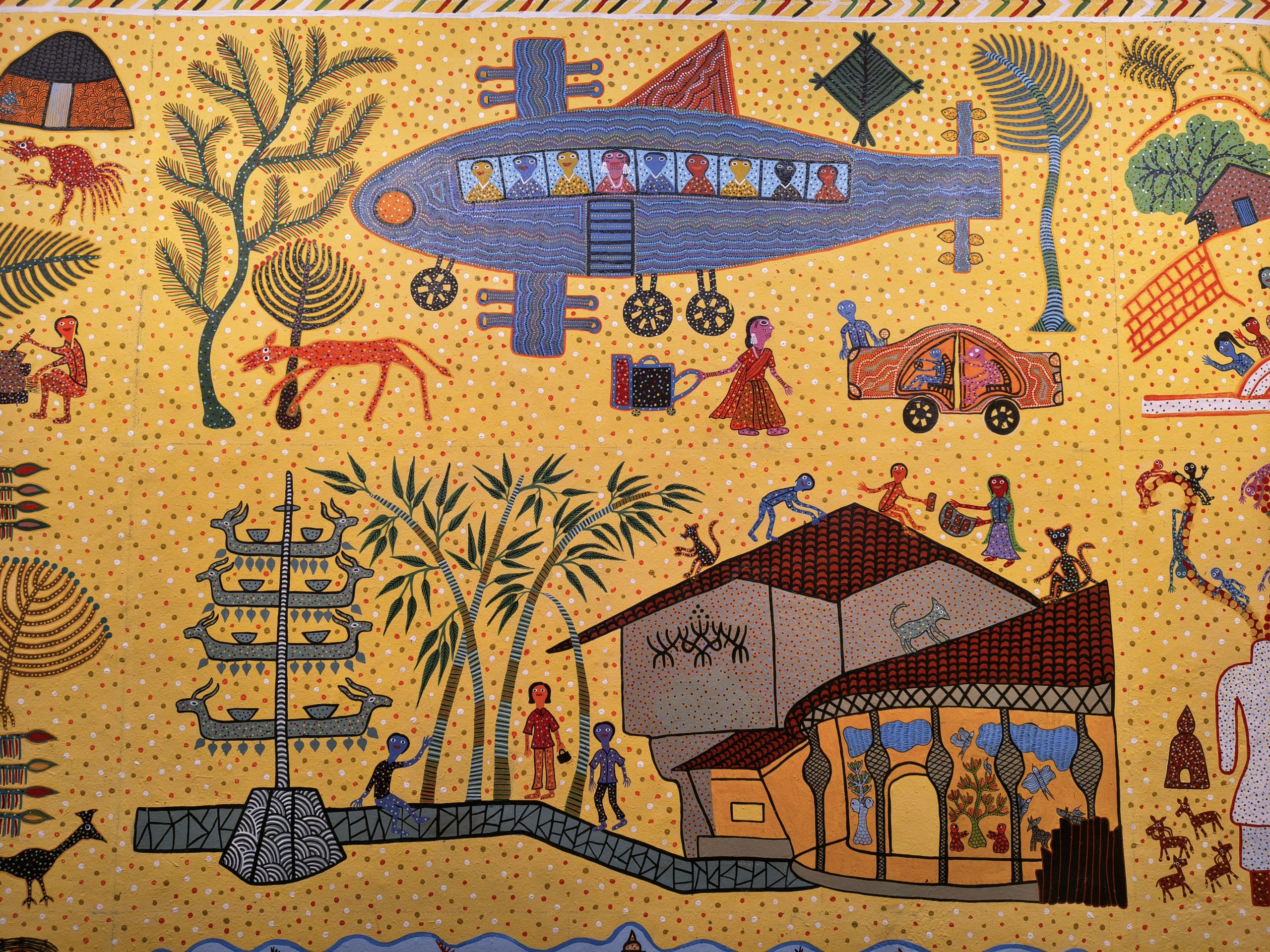

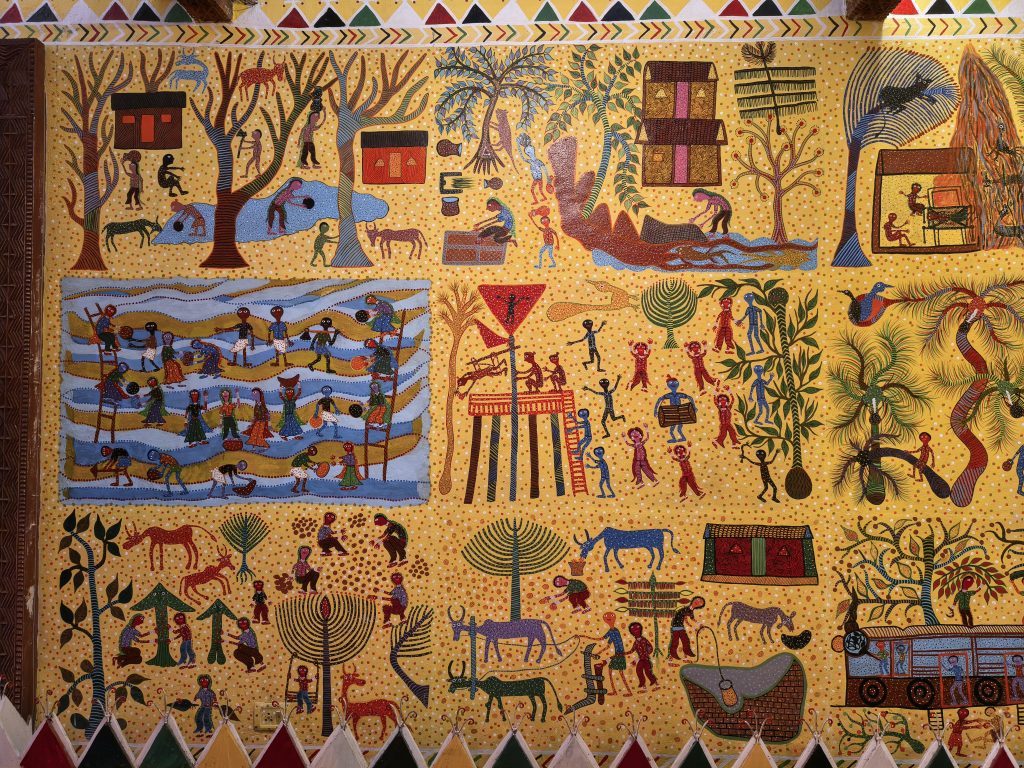

The ‘Aadivart’ State Museum of Tribal and Folk Arts in Khajuraho silently houses a mural painted by Bhuri Bai on the walls inside one of the galleries in the museum. Bhuri Bai actually came to the place and painted the mural herself. It was no replica. Bhuri Bai had touched these walls. There is contact. Another mural by Durga Bai Vyam chronicling Narmada’s journey spirited another room under the same roof.

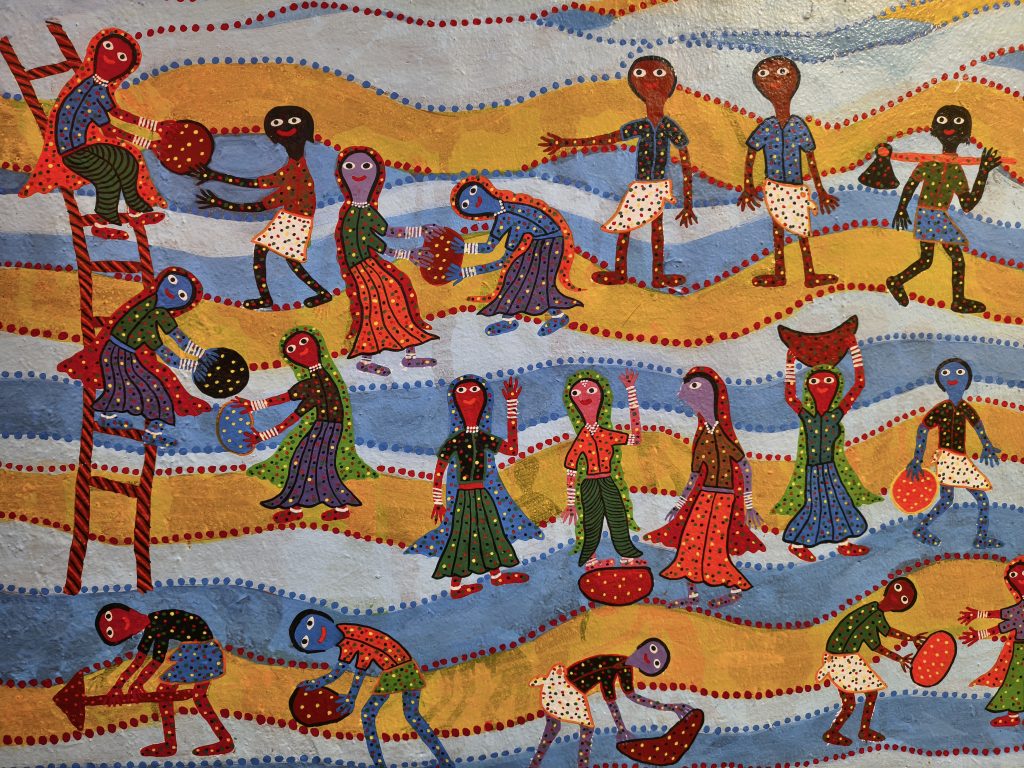

The room basks in the brilliant glow from the painted walls. In the middle of the room is a heap of terracotta animal figures dedicated to the tribal deity Baabdev. There is, to borrow from Cixous, a different ‘music‘ in Bhuri Bai’s vision. It calls for a different sensibility where negligence finds no place. Rushing through her vision, like tourists do, would be a shame. Her vision does not admonish. There is no clamouring for approvals. Instead, she welcomes us into a patient mindfulness with which we learn to labour to listen to all who are subdued, to all whom we have subdued.

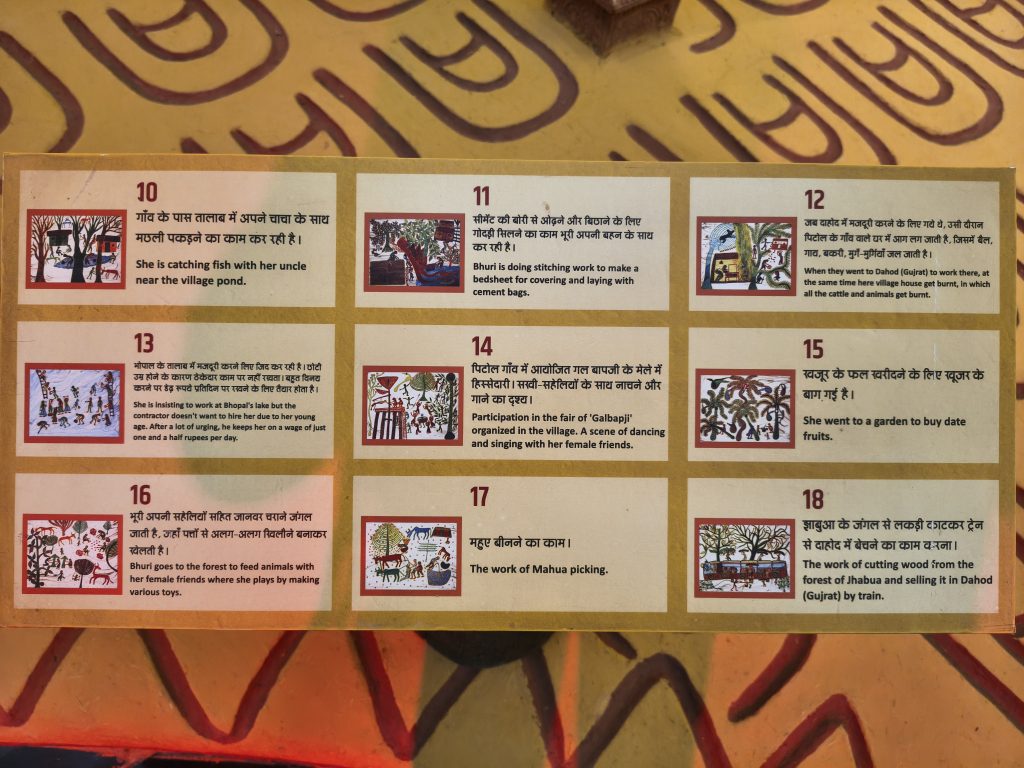

Bhuri Bai’s mural is her memoir. While the entire mural looks like a single painting, which it is, it can be actually read in thirty-six parts that chronicles her journey. This was her vision for Aadivart. But the mural is continuous and everything intersects. Her laborious agrarian origins are inextricably linked to her making as a kalakar. She has expressed labour without resentment. On a yellow backdrop, myths symphonised memories in a dominant rural-tribal style as if the rural origins are reluctant to get erased. Rather, Bhuri Bai’s expression of her experiences with the artworld is not forgetful of her Adivasi origins. Every stroke made in the mural acknowledges that it is who she is—an Adivasi woman who had to work her way through to where she is. This is an expression of resilience, particularly today when histories are being mutilated and it is becoming difficult for women to freely express without censorship.

Invitation

Would Bhuri Bai—being an Adivasi woman—have found her voice in any way other than her ‘art’? Would she have managed to realise herself as an ‘artist’ and activate ‘art’ in her and hundreds of others like her had it not been for her fame? Is it all accidental? If there was no Bhuri Bai, who would have inspired the women from the Bheel community to come and paint? Would Basanti Tahed have gotten the same freedom if she had had somebody else other than Lado Bai as her mother-in-law? Is there any other way to call it other than ‘art’? Has it got the potential to serve as a medium of Adivasi and Dalit self-expression and survive in the world of professionalised ‘art’? Do we have to categorise these expressions as ‘art’ and let them be annexed into the grand project of appropriation which is what the art market is all about?

We know that Pithora tradition is a practical discipline among the Bheels. Pithora is a part of their collective tribal memory, their sense of tribal spirit. It is their Lok-Darma. But do we simply look at Bhuri Bai’s mural-memoir as an autobiographical chronicle that captures the collective tribal continuum her mind is part of? Or is it something more? An invitation, perhaps?

A label reads: “Bhuri goes to the forest to feed animals with her female friends where she plays by making various toys.” There is a placid acknowledgement of sisterhood in Bhuri Bai’s mural-memoir. Despite the fluidity with which it has been represented by her, we, by no means, cannot give in to romanticisation. Agricultural work is toilsome and laborious. Yet the faces painted by Bhuri Bai are without grimace. Her sisters work the fields, tend to the cattle, carry harvest, climb trees, sing, dance, build, but they are never disengaged from each other. The world her mural shows is one where sharing and caring intersect. It is a world that acknowledges the value of labour. It is a vital world.

Bhuri Bai’s mural-memoir is a Likhandara’s archipelago where everything resonates and reciprocates. ‘Likhandara’—someone who writes a lot. This means ebullience. It is the same spirit of which Audre Lorde wrote about in her Cancer Journals. It is the same spirit which Cixous wants women to unleash. It is the same spirit with which the likes of Bhuri Bai, Durga Bai, or Lado Bai have picked up their brushes. Bhuri Bai’s painting is the Adivasi woman’s ebullience inviting all women, particularly all Adivasi and Dalit women, to express themselves ebulliently and overflow. If language is unjust, which it oftentimes is, or has stolen our trust, then do away with language and discover new ways of expression. Let not form debilitate what can otherwise flow freely without it.

About the author(s)

Subham is from West Bengal. He daydreams to be a traveller and a writer he knows he shall never be. Trees and music stir a tender sense of empathy in his heart. He wants to apologise to the trees.