Art history often pretends to be a meritocracy, that the best work inevitably rises to the top. But for women and queer artists, visibility has rarely been a reward for brilliance. It has been something negotiated, bargained for, or stolen back from systems that were never designed to see them. Across centuries and cultures, their creative labor has been dismissed as amateur, decorative, immoral, or politically dangerous. To survive within patriarchal art worlds, many were forced to change how they looked, how they named themselves, and how their work circulated. Some wore men’s clothing. Some used male pseudonyms. Others accepted misattribution or anonymity, not because they lacked talent, but because credibility itself was gendered.

This is not simply a story about individual artists. It is about how erasure became a structure and how women and queer creators turned that erasure into embodied resistance.

Patriarchy made art “male”

From European academies to global art markets, artistic institutions have historically privileged men. Formal training, studio access, professional networks, and public legitimacy were reserved for male creators. Women were expected to produce art as a hobby, not a profession. Queer identities, when acknowledged at all, were treated as deviant or pathological.

To survive within patriarchal art worlds, many were forced to change how they looked, how they named themselves, and how their work circulated. Some wore men’s clothing. Some used male pseudonyms.

These hierarchies shaped what was considered “real” art. Women’s labour was coded as emotional, domestic, or secondary. Queer expression was sanitized or erased. To be taken seriously, artists had to conform to norms of masculinity, respectability, and heterosexuality.

When women had to disguise themselves

In 19th-century France, animal painter Rosa Bonheur was internationally celebrated, yet she was legally required to obtain police permission to wear trousers in public. This was not a fashion statement but a professional necessity: trousers allowed her to enter male-dominated spaces like slaughterhouses and horse markets to study her subjects. Her masculinity was a condition of access.

In literature, similar strategies emerged. Amandine Dupin became George Sand so her novels would not be dismissed as women’s writing. The Brontë sisters published as Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Mary Ann Evans wrote as George Eliot. Their talent was undeniable, but their credibility depended on male names. These women did not reject their identities; they rejected a system that equated authority with masculinity.

For some women, even disguise was not enough. Margaret Keane’s iconic paintings were sold under her husband’s name for years. Sculptor Camille Claudel’s work was long subsumed under Auguste Rodin’s reputation, with her brilliance reframed as influence rather than authorship. Judith Leyster’s paintings were attributed to Frans Hals for centuries until scholars rediscovered her signature. These were not mistakes. They reveal a pattern in which women’s labor is absorbed into male genius because institutions find male authorship more credible and more profitable.

Queer artists and the politics of erasure

Queer artists have often been erased not through absence but through distortion. Frida Kahlo’s bisexuality, gender-nonconforming presentation, and political radicalism are frequently reduced to footnotes in narratives that frame her primarily as Diego Rivera’s suffering wife. Yet her self-portraits challenge heterosexual femininity and insist on a body that is desiring, defiant, and political.

Margaret Keane’s iconic paintings were sold under her husband’s name for years. Sculptor Camille Claudel’s work was long subsumed under Auguste Rodin’s reputation, with her brilliance reframed as influence rather than authorship.

Surrealist Claude Cahun rejected binary gender identities through radical self-portraiture decades before such ideas entered mainstream discourse. Their work was ignored for much of the 20th century precisely because it destabilized fixed notions of selfhood. Romaine Brooks painted queer and androgynous figures in the early 1900s but was excluded from canonical modernist histories.

Today, Zanele Muholi confronts this erasure by documenting Black queer and trans lives, producing images that are both art and archive. Muholi’s work insists that visibility is not decorative; it is survival.

Indian contexts: when women’s art becomes “craft”

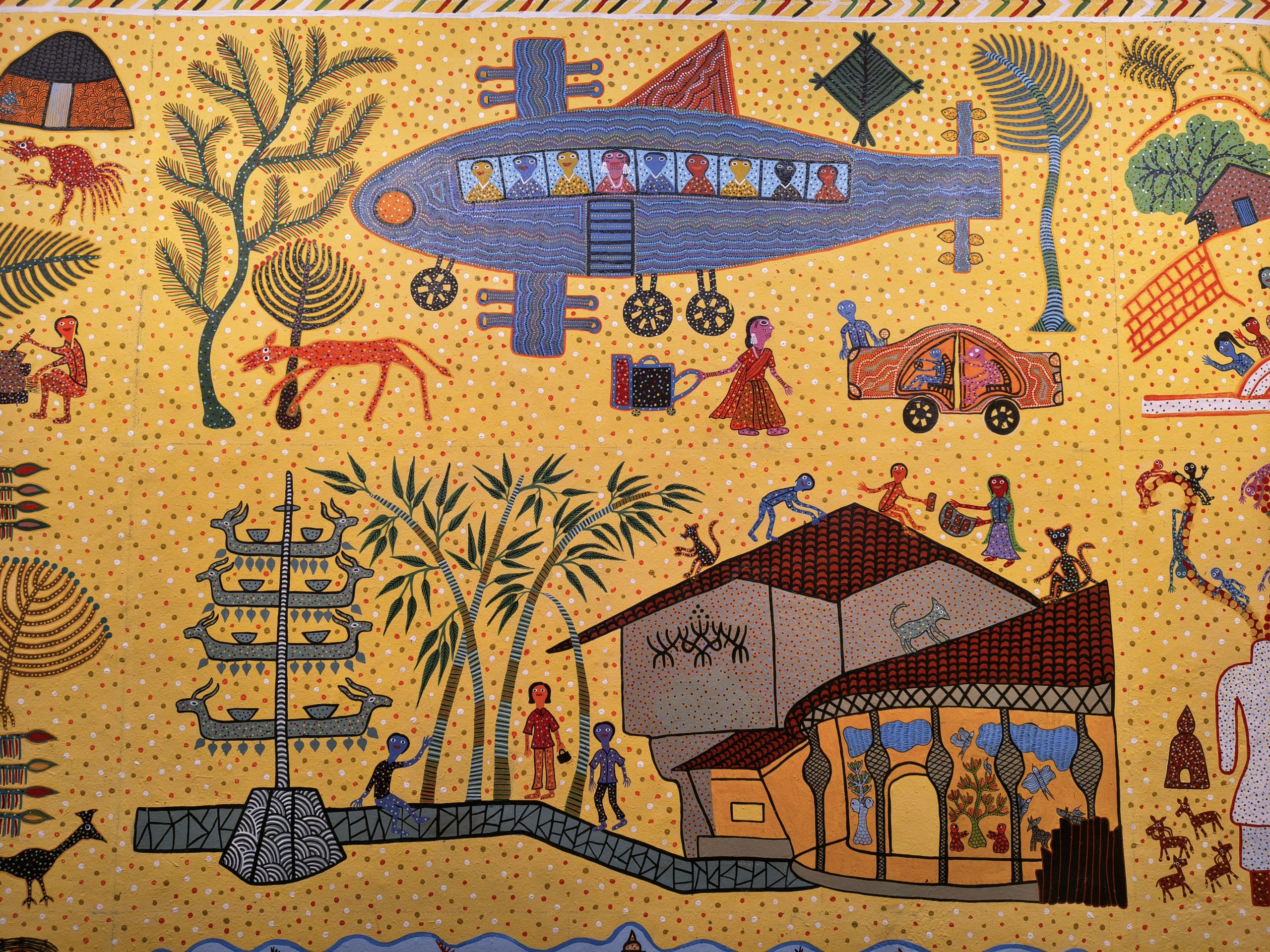

In India, women’s artistic labour is often marginalized through classification. Art forms such as Madhubani, Gond, Warli, Phulkari, and Kalamkari are sustained largely by women. These practices are rich in symbolism, history, and community knowledge. Yet they are frequently categorized as “folk” or “craft” rather than fine art, a distinction that devalues both the work and the maker.

Textiles, embroidery, and domestic arts, overwhelmingly produced by women, are treated as cultural heritage rather than intellectual labour. The label of “craft” allows institutions to celebrate beauty while denying artistic authority. For Dalit women artists, this erasure is compounded by caste. Their work is often consumed as ethnographic material rather than recognized as political and aesthetic intervention. Who gets to be called an artist in India remains deeply shaped by gender, caste, and class.

Contemporary art institutions speak the language of inclusion, yet disparities persist. Women and queer artists receive less funding, fewer exhibitions, and lower market value. They are often invited to represent identities rather than to shape discourse. Visibility remains conditional. Women are celebrated when they are palatable. Queer artists are welcomed when their politics are softened. The structures of power remain intact.

For women and queer artists, being seen has never been neutral. It means being recognized as a creator, not a muse; as an author, not a footnote; as an artist, not a nameless contributor to tradition. From Rosa Bonheur’s trousers to Dalit women’s textiles, from Claude Cahun’s self-portraits to queer folk traditions, the struggle has always been the same: to exist publicly without having to disguise, dilute, or apologize for oneself. Art is never separate from power. Whose bodies are allowed to create, whose stories are archived, and whose labor is valued are political decisions.

To recover women and queer artists is not to politely add them to a canon built without them. It is to challenge who that canon was designed for and to insist that visibility itself is a form of resistance.