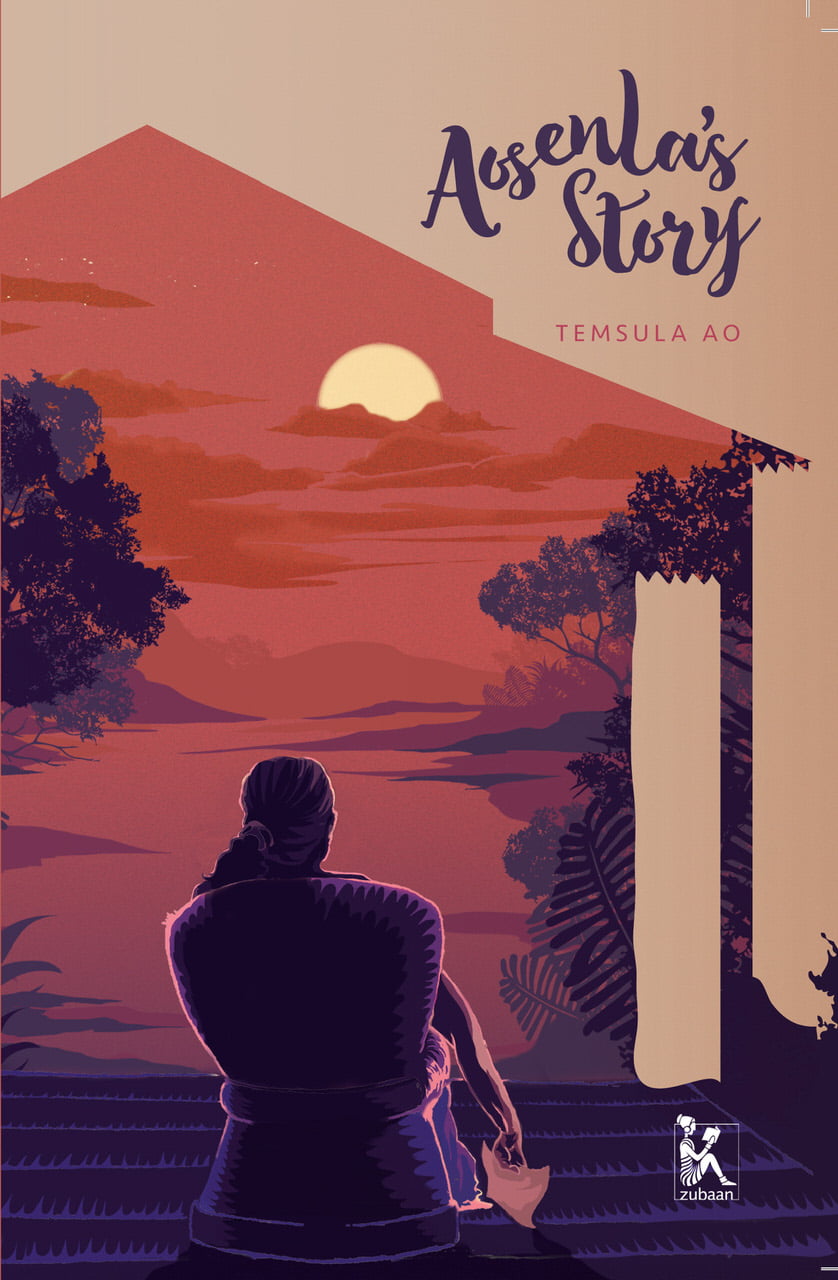

In her new book Aosenla’s Story, poet and writer Temsula Ao returns to her beloved Nagaland to bring readers the beautifully crafted story of Aosenla, a woman who is coming to terms with herself. Looking down at a wedding invitation in her hands, Aosenla begins to recall her own wedding ceremony many years ago, initiating a deep and moving reflection on the parts of this life that were made for her, and the parts she has made for herself.

Seventy-year-old Temsula Ao is a pioneer of northeastern Indian literature, who was recognized with India’s highest civilian honor in 2007 for her work. The author of many volumes of poetry and short stories, Ao published her third book with Zubaan.

It was a typical summer afternoon, turning into another, predictable, oppressive evening. The atmosphere was still heavy with the accumulated heat of the day. The anticipated coolness of dusk was some indeterminate distance away.

Amidst the gathering interplay of fading light and threatening darkness, a first-time visitor could make out the outlines of a big estate, which appeared to be gradually coming to life. The two houses within were still visible: the big one with its imposing façade and the smaller one, almost demure, in its country-cottage sereneness. A few disjointed sounds of water running from taps, garbled human voices, and the clatter of utensils wafted out from the house. In the verandah of the smaller house, a lone figure sat in the gathering dusk, quiet, seemingly indifferent to the sounds and smells of the darkening day.

The woman sat, listening with only half an ear to the racket her children and their friends were making in the grounds adjacent to their grandfather’s sprawling compound. For some time now, she had wanted to tell the maid that it was time to bathe and prepare them for the evening’s rituals. But somehow she remained quiet, as if she lacked the will or energy to do anything. Her gaze drifted towards the big house, the house that had symbolized authority and domination over her life ever since she had entered it as a daughter-in-law.

She wondered how an inanimate object like a house could wield so much power. Was it the structure, which tended to dwarf the smaller one that she could at least call her own? Or was it the aura of the people who lived in the big house, who seemed so sure of themselves, and at every given opportunity tried to remind her of her origins and her place in life? A summons to the big house always made her cringe; had she done anything to displease the gods residing there? Or would she receive new diktats about an impending family event?

As she continued to gaze at the formidable structure, she willed her attention back to the verandah of the smaller house where she was sitting; this had been her ‘home’ since she got married. Within these walls, she grudgingly admitted, she had enjoyed at least a certain amount of freedom and even an occasional happy moment. But once she stepped outside its perimeter, she was no longer her own self; she was the wife of a rich man and the daughter-in-law of an influential family. She no longer had an independent identity.

As she turned her attention once again to the big compound, she could see her mother-in-law, big in size as well as in pride, ordering the gardener and an assortment of servants to restore the landscape to its original condition, before the children had created the mess.

An older man, and the gardener were trying to say something in reply to a command, ‘Otsu, Otsu, Obou said…’ But before the gardner could say anything further, the matriarch shouted back at him, ‘Never mind what the old man said, do as I told you’, and haughtily walked into the house, leaving him dumbstruck and the other servants giggling at his discomfiture. As if to remind them of what they were supposed to be doing, there came the strident voice of the matriarch shouting at the cook over something he had or had not done.

Aosenla took in the various nuances of the domestic drama and marvelled at the negative energy of this formidable woman. She was glad that she was not directly under her command in these daily routines, thanks to the age-old custom that required the sons to set up a separate household after marriage. The problem was that their new home was within the big estate, and therefore the old couple still managed to dominate the new household in more ways than Aosenla liked. But she had to live with this semi-independence and was ever careful to avoid any direct contact or conflict with people in the big house, especially her mother-in-law.

Excerpted with permission from Aosenla’s Story, Temsula Ao, Zubaan. You can buy the book here.

Also read: Aosenla’s Story: Traversing Through Self-Doubt And Power Dynamics

Cover design and illustration by Ujan Dutta

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.