Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.

Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.One of the most glaring problems with how the media reports gender-based violence is its use of sensationalist headlines. With the media turning into an industry, headlines compete with each other to grab the most eyeballs – where keeping the sentiments of the survivor in mind is sacrificed at the altar of TRP ratings and sales. While it is important to draw attention to cases of rape and gender-based violence, it is equally important not to turn a grievous crime into a media circus – something that begins to resemble entertainment.

Sensationalist headlines tend to provoke the reader, highlighting the case’s “unusualness” and creating a spectacle out of the crime. They highlight the most barbaric aspects of the crime, and frame it in a way that is designed to inspire shock, horror and disgust. The perpetrator/s are characterised as monsters – outliers of society.

These types of headlines emphasise the singularity of this particular crime – isolating it from the structural nature of gender-based violence. They lead the audience to believe that this particular rape, or gender-based violence was a one-off case, perpetrated by an extremely violent or barbaric person/group. They highlight the “unusualness” of the crime, rather than its systemic nature.

The truth is that gender-based violence is a shockingly common phenomenon. It happens everyday, to millions of people, perpetrated by millions of people – many of whom that would never be characterised as “monsters” or outliers of society (think of the so-called respectable men that were called out during #MeToo). The solution to gender-based violence has to come from a systemic overhaul of society, not by focusing on the barbarism of a single case.

With the use of the word ‘monster’ to describe the perpetrators of certain rape cases, similarly, we take away from the ubiquity of sexual violence. It makes it harder to understand that gender-based violence is not only a crime that happens in shady alleys and dark corners by strangers who are ‘monsters’ (and many of these monster characterisations intersect with class and caste discrimination, with Dalit and Muslim men being seen as “dangerous” or “violent”). It makes it harder to understand that gender-based violence happens as often, if not more, within homes, workplaces and families. It makes it harder for survivors to speak out about rape committed by those viewed as “respectable members of society”, because people are likely to say, “But he would never do something as horrific as that!”

Also read: The Problem With The ‘Monster’ Theory Of Rape

By sensationalising certain cases, the media creates a yardstick through which the public may determine its outrage. The Delhi 2012 gang-rape, called the “Nirbhaya” case, is a good example. Nirbhaya became the yardstick on which all future crimes of gender-based violence were ‘rated’. If it was “more brutal” than Nirbhaya, it was deserving of attention. If it is “less brutal”, then it doesn’t deserve front page headlines, outrage or protest. All cases of gender-based violence are brutal, all of them deserve outrage. The selective sensationalism of certain cases that are extra barbaric makes the audience numb to “smaller” incidents of gender-based violence.

Gender-based violence is a traumatic occurrence. Millions of women suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder after experiencing GBV. Headlines focussing on the excessive barbarism of a crime can also be very triggering for survivors of GBV – and especially for the survivors of the specific crimes being reported about. The media should keep in mind that a large chunk of its audience are not just consumers, but people who have experienced gender-based violence, in order to frame headlines with greater sensitivity.

Trigger warnings are a common and sensitive way to warn the audience about what they are about to read. If not in print media, trigger warnings can easily be used in digital media, and in social media copy text.

Sexualising Gender-Based Violence

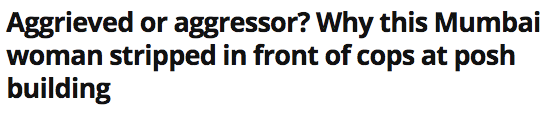

Another form of sensationalist headlines are those that attempt to turn a case of gender-based violence into a sexualised event.

In the case above, a woman called the cops after she got into an altercation with a security guard. However, the police constables who arrived at the scene were forcing her to come to the police station late at night, despite the absence of a female constable (which is illegal). She stripped in order to protest the incident and to prevent the police from harassing her further. However, in this article, a story of harassment is turned into a provocative headline. For instance, using the terms ‘posh building’ could imply that the woman is wealthy and “loose”. The headline could have been framed in a way that highlighted the woman’s distress rather than the act of “stripping in front of cops”, which has sexualised undertones.

Also read: How Can The Media Report Violence Against Women More Sensitively?

In Tamil Nadu, the Pollachi sexual abuse and blackmail racket made headlines when it was found that a group of men raped, harassed and exploited dozens of women for a span of seven years and then blackmailed them with video clips of the assault to stay silent. During the coverage of this case, one media platform chose to upload one of these blackmail videos, with the survivor’s face blurred out, on its platform, turning a horrific and traumatic event into a lewd and voyeuristic incident that made a mockery of the privacy, dignity and the mental health of the survivor.

When reporting gender-based violence, it is advisable to give as much detail as strictly necessary without resorting to salacious, provocative or titillating words and images. A play-by-play recounting of the assault for instance, creates a voyeuristic gaze and is wholly unnecessary.

And then of course, there are shows like ABP News’ Sansani (literally translating to ‘Sensation’) that has created a theatrical retelling of a case where a man has burned his entire family after molesting, and later being rejected by his wife’s sister – complete with over-the-top narration, sound effects and facial expressions by the paid actors. (One small silver lining – this episode aired 3 years ago, and the show since appears to have stopped undertaking theatrical recreations of GBV crimes.)

About the author(s)

Asmita is a Freelance Communications Consultant, and specialises in leading digital advocacy campaigns for social and gender justice issues. When not using social media for work, she uses social media for fun (and a healthy dash of existential despair).